Absolute Value

On teaching physics with optimism despite its bad reputation and what and who physics may actually be for

Hi and thanks for subscribing to my newsletter! The breakdown: first a personal essay then some thoughts on my recent work, things I am reading, writing and listening to and finally some recipes and recipe recommendations. Feel free to skip to whatever interests you. Please do also hit reply at any time, for any purpose - these are odd times and I want to offer as much connection and support as I can. Find me on Twitter and Instagram too.

ABSOLUTE VALUE*

Physics has a bad reputation. When you are a physicist, that bad reputation tends to follow you around. When you tell people what you do, they either don’t believe it if you don’t fit their extremely narrow preconceived notion of a physicist. Alternatively, they immediately assume you must be a true genius. Sometimes they feel compelled to mention that they hated physics in highs school or in college. Similarly, students who are not physics majors, but have to complete a physics course as a graduation requirement often approach it with apprehension. They tend to blame their struggles with the material on the subject itself, assuming that there is really no way for it to be anything other than confusing and difficult. Even other scientists will sometimes speak about physics with a mix of intimidation and envy, assuming that because of the division between theoretical and experimental work and the centuries of mathematical underpinnings that physics has, it has to be the most correct science, the most objective science and a science that is the least accessible to a non-expert. When faced with the question of how to explain what physics is, who it is for and what it’s purpose is, to a teenager who may have only had a limited exposure to formal science so far, a teacher or a practitioner is really dealing with as much emotional baggage as they are with intellectual challenges.

Despite having taken my first physics class when I was in the seventh grade, I can’t say that I remember ever having a “big picture” conversation about physics with any of my teachers. They did not find it necessary to explicitly debate why I should care about physics or whether physics is for me. Courses would mostly just plunge in, immediately confronting students with jargon and busy blackboards. In addition to being left to reason out what physics is and what it is for– certainly made easier by the fact that I was very early on very driven to just learn as much as I could – I was also left to learn why there were so many bad feelings that mentioning physics conjures up and what exactly I should do with them. In my years training to be a physicist I certainly encountered a fair share of those, in casual conversations with others or even more forcefully lobbed at me by a voice inside my mind. Finding myself in the teacher role now, and one where I have plenty of freedom to sneak-in a more meta conversation into the syllabus here and there, I am thinking about my experience and wondering how dissonant it is compared to what I expected in the seventh grade. More importantly, I have to decide how much dissonance I should allow between that experience and what I tell my students about physics and physicists.

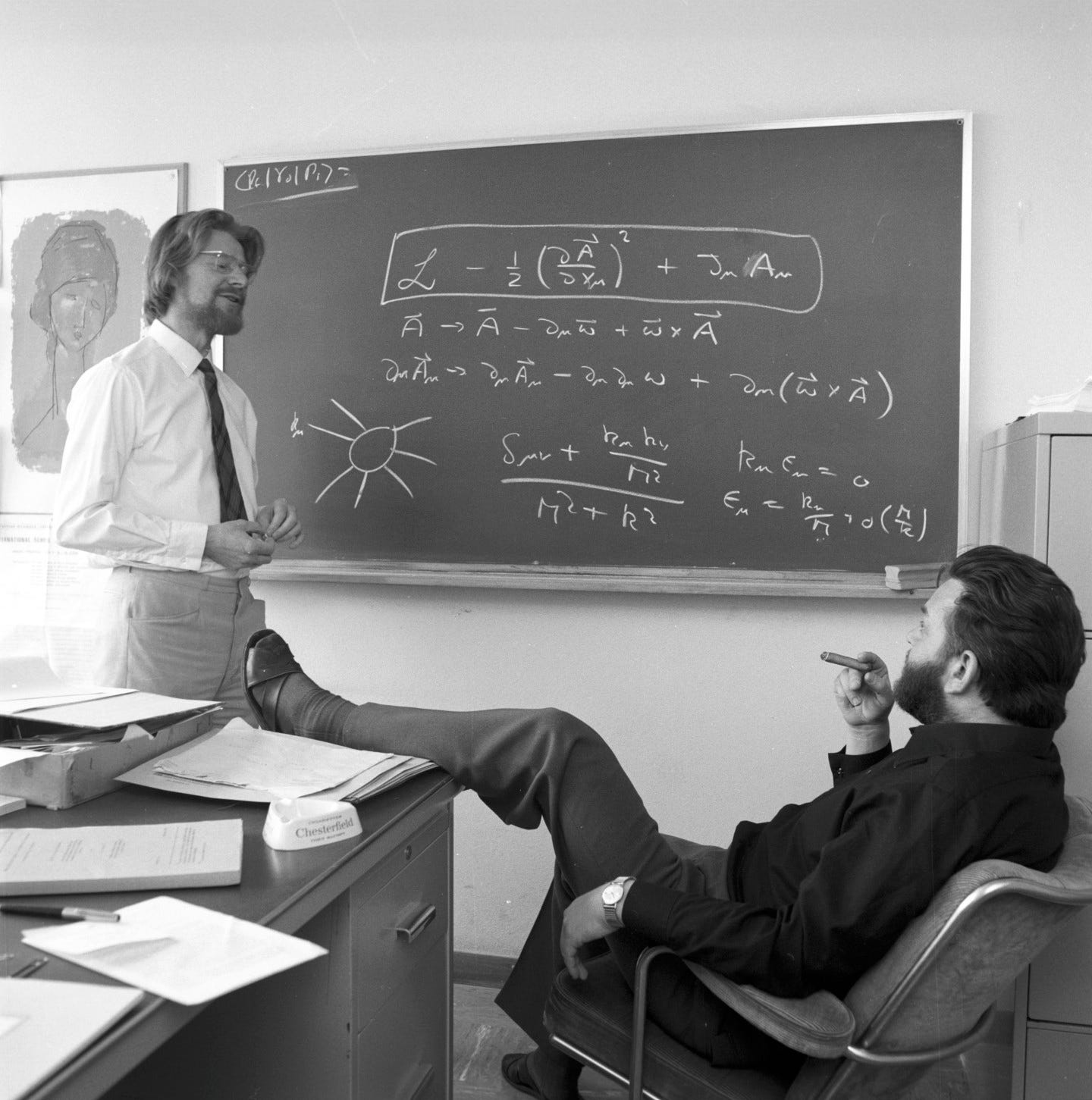

Photo: an image accompanying a rather odd article titled “What is a theoretical physicist” on the CERN website. It claims that typical scientists are “absent-minded, egg-headed, bizarre characters scratching their chins while deeply engaged in thought.”

***

Another important part of the process is a social one, the communication of your theory and experiments to colleagues. Submitting your ideas to the criticism (at times blunt) of your peers is crucial to the advancement of science. Communication is also important in assuring your own care in performing the experiments and interpreting the results. A scathing attack by someone who has found an important error or omission in your work is a strong incentive for being more careful in the future.

The Physics of Everyday Phenomena, W. Thomas Griffith and Juliet W. Brosing, 7th edition

***

Turning to textbooks that are recommended for a 9th grade conceptual physics course, like the one I am in the process of designing, I am confronted with both an idealized version of physics (and science more generally) and one that does not shy away from being cold and intimidating. While I was not surprised to see physics lauded as the most quantitative science, the most basic science and the most fundamental science, I did not expect paragraphs explaining to students that a good way to make sure you are doing your science correctly is to have your colleagues potentially rip you to shreds. Certainly, expectations of “blunt criticism” and “scathing attacks” do not sound inviting nor do they serve to make the field seem more welcoming to those that may already feel like outsiders. And some of these texts would have you believe that this is a crucial ingredient for keeping scientists honest and diligent and therefore successful.

While I have written about peer review critically in the past, I do not deny that it is, at least as an idea, a facet of professional science that cannot be done away with. Over the years I have become convinced that science is a team sport and a community effort above all. Having someone to bounce ideas off of, someone to check your work, someone to think of explanations of experiments and phenomena alternative to yours is invaluable. However, those relationships should be rooted in mutual-trust and something like team spirit and a shared goal rather than shame and fear. But there is often a sense of fear in physics gatherings, an acute awareness that in each group or seminar there will be at least one person just looking to shut your idea down. We excuse hostile behavior, however, as an unfortunate necessity of the job. We know we have a bad reputation when it comes to social graces, but we are also a little proud of it because we think it makes our work better. As physicists, after all, we are at the top of the science pyramid, and that has to call for some tough love and ruthless standards – or so the thinking may go.

Trying to rank sciences or assemble them in some hierarchy, whether it is one of usefulness or some sort of academic abstract excellence, hurts all scientists. People that direct funding for the sciences are rarely working scientists and more and more of big research universities are run like business rather than institutions aimed at, well, making the world better. To the mind of a business manager a ranking of sciences may read as a cheat-sheet for allotting more money to one type of research and abandoning other efforts. While some research groups and departments benefit from this, it establishes a dangerous precedent. Once you decide some sciences are just not worth the resources, you open the door for narrower and narrower definitions of worth and more and more defunding of research and teaching. Even if physics is the purest and most fundamental, some parts of it could be deemed as even more that. Discarding of other parts, or slowly killing them off via lack of support, ultimately makes the whole field more intellectually poor. Often best ideas come from interdisciplinary collaborations, unintended inspiration from a random talk or a class, or just unconventional thinkers that are allowed to jump and intersect various niches.

***

Q14. Which of the three science fields—biology, chemistry, or physics—would you say is the most fundamental? Explain by describing in what sense one of these fields may be more fundamental than the others.

The Physics of Everyday Phenomena, W. Thomas Griffith and Juliet W. Brosing, 7th edition

***

Is it factually true that biology sort of rests on a foundation of chemistry and chemistry sort of rests on a foundation of physics? Sure, ultimately everything reduces to just electrons and protons moving around. That simple fact, however, should not be taken as a signal of some physics exceptionalism. Many scientists, doctors and engineers do very well without a deep knowledge of physics or only a cursory familiarity with the bits and pieces that are folded into their work without much noise. The desire to convey to a young student that those bits exist and that the study of physics can be valuable even for those whose heart is not set on a future in physics is understandable. At the same time, there must be a way to motivate them without asserting that physics is a science that carries many superlatives and that everything else absolutely depends on it.

This conviction and an often not-so-subtle assertion that physics is somehow better than other sciences further plays into the ideas of the physics community being unwelcoming and cold or physicist being awkward or conceited. Just imagine it – in a science so fundamental and so important how could successful scientists be anything other than geniuses? As with so many things we think should be meritocratic, this attitude opens the doors for exactly the opposite of meritocracy. In other words, it is not so much that the smartest and the bravest and the most committed succeed as much as it is that everyone who has not been brought to believe they could be a physics genius ends up struggling. As physics has historically been overwhelmingly male and white (something not mentioned in either of the textbooks I have been consulting while designing my course), the conflation of a physicist with a lone, independent genius becomes a conflation of both of those persons with a white man. There are still fewer than 20% female faculty and fewer than 10% Black faculty in physics departments across the United States. If the field were seen as more friendly, more accessible and less invested in being the purest and most important, maybe its culture would not be an obstacle to more talented scientists from these traditionally underrepresented groups to join in and genuinely succeed. It is in no way a coincidence that many successful physicists have one or more parents that are also successful academic scientists and that they often couple up with other academic scientists (something I am also guilty of). Looking from the outside, many facets of science can look like closed loops to such an extent that they cannot be anything other than exclusionary. The problem is partly that those of us on the inside tell ourselves that what we project to the outside is nothing but pure curiosity, wonder and enthusiasm for knowledge and invention. The reality simply does not always reflect that.

***

In the scientific spirit, a single verifiable experiment to the contrary outweighs any authority, regardless of reputation or the number of followers or advocates. In modern science, argument by appeal to authority has little value. Scientists must accept their experimental findings even when they would like them to be different. They must strive to distinguish between what they see and what they wish to see, for scientists, like most people, have a vast capacity for fooling themselves. People have always tended to adopt general rules, beliefs, creeds, ideas, and hypotheses without thoroughly questioning their validity and to retain them long after they have been shown to be meaningless, false, or at least questionable. The most widespread assumptions are often the least questioned. Most often, when an idea is adopted, particular attention is given to cases that seem to support it, while cases that seem to refute it are distorted, belittled, or ignored.

Conceptual Physics, Paul G. Hewitt, 10th edition

***

While I do not think that many physicists are rude on purpose or that they set out to be unfriendly, I have often gotten the impression that many just buy into the heavily idealized version of physics a bit too much. This ten leads them to never question how their own behavior contributes to sometimes not-so-great norms of the whole community. Peer review is in part such a sticky topic exactly because it is supposed to keep us honest and make us rely on science rather than unfounded reverence for some personality or fear of some authority. When an author writes about scientists not caring about opinions of authority figures and relying on their empiricism only, they probably have in mind Galileo Galilei or Giordano Bruno fighting religious persecution. They do not imagine a talented young physicist unable to publish revolutionary work, or find a well-paying research position, because no one who is famous in the field is attached to their name or they come from a small institution or they just stumbled upon an unfair reviewer who is, again, likely to be a figure of authority. Within the field of physics, we certainly have our own figures of authority and our own internal trends which we are not immune to. These notions again trickle up towards those that determine what sort of physics is worth the monetary support thus creating even more of an imbalance among us.

The most striking thing, to me, has always been that so many older, more established, physicist claim that they are friendly and that they want to talk to anyone about their work. They all want to be inspiring and light a science fire in the hearts of the youth. I am sure that this what they truly feel and that this is what they think they are sinking their energy into. Those same people however will often feel fine teaching “weed out” courses, claiming their science is the most objective, and arguing that one’s identity and personal background do not matter for their success in physics, or science more generally. In part, I believe, this is why so often diversity issues in physics are addressed with countless outreach programs and never-ending talk of broken pipelines. These approaches to making the face of physics look differently do not solve cultural issues within physics. They only bring more people into a position to be convinced that they are not good enough, or not wanted enough, to be the kind of physicist that inspired them to join in in the first place. It is absolutely true that if our science were so pure, so fundamental and so objective that all that is on display is its beauty and wonder, then these programs would work and every traditionally underrepresented kid that gets inspired would go on to be a big deal physicist. But in reality, people are messy, and communities are messy and so our science too is, at times, quite a huge mess.

***

Physics is more than a part of the physical sciences. It is the basic science. It's about the nature of basic things such as motion, forces, energy, matter, heat, sound, light, and the structure of atoms. Chemistry is about how matter is put together, how atoms combine to form molecules, and how the molecules combine to make up the many kinds of matter around us. Biology is more complex and involves matter that is alive. So underneath biology is chemistry, and underneath chemistry is physics. The concepts of physics reach up to these more complicated sciences. That's why physics is the most basic science. An understanding of science begins with an understanding of physics.

Conceptual Physics, Paul G. Hewitt, 10th edition

***

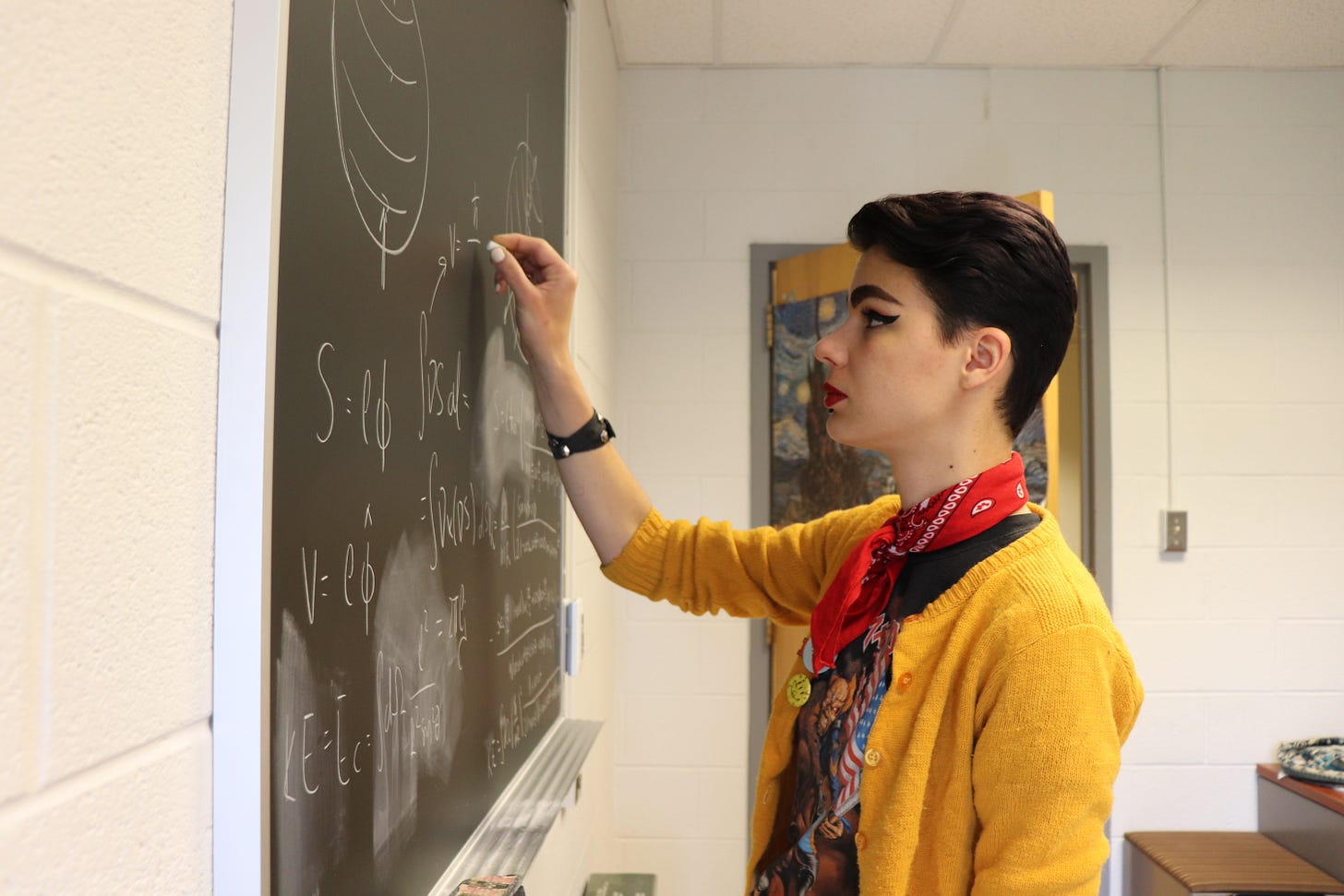

Photo: me, a real life theoretical physicist, hopefully not a bizarre character

A month ago, when I was researching my profile of Prof. Debbie Jin for Massive Science, a collaborator of hers mentioned that she never felt comfortable giving big speeches about the status of women in physics, but still cared about it deeply. They insisted that she invested a lot of time into thinking up the best way to address the issue. As in her science, she wanted to be precise and use her strengths effectively. Ultimately, she settled on expertly leading by example. Weighing all the possible means for bettering her community led her to think that she should be a dedicated mentor, a stellar communicator and by all means a role model. While having this conversation about Jin, I was struck by how correctly she judged her skillset: I had personally been inspired by her. I saw her give one speech and immediately decided she would be one of my heroes going forward, a hero who did not seem that far removed from what my future might be. I am grateful for that – for her clarity, her positive presence, her friendliness and her being a different kind of success story than the many, frankly, old white men I had always imagined myself growing up to be.

Getting ready to step into my 9th grade classroom in a few weeks, I am thinking about Debbie Jin much more than I am thinking about whether physics is the most fundamental and the most mathematical or whether scientists are the most honest profession and most tightly policed by their peers. In my time training to become a physicist I have certainly not benefited from being intimidated or afraid and, much as I imagine a parent might, I worry about passing those bad feelings on to my student, even just unconsciously. What I do want to pass onto them is hope and conviction that though it’s a tough field at times, it is possible to make it through, the certainty that if you have curiosity then you should belong even though some of your peers may not think so. I want to be a one-person PR firm for the good things I encountered as a physicist: the camaraderie among women and queer folks, the openness of unexpected collaborators, the rare administrator that was actually willing to listen, the long distance acquaintance that always checked-in on ongoing projects, and so much of that famed inquisitiveness and love of discovery that can sweep you up off your feet even when it feels like the system is rigged against you. Nevertheless, I also don’t want to sell them some idealized idea of science, something very near to ideology that can serve to cover-up our human failures that undoubtedly affect our intellectual successes. Finding balance between these two impulses is tricky.

I have been frustrated with textbooks that turn a blind eye to the homogeneity and the bad reputation of physics. The fact that textbooks represent figures of authority and they do not address anything but a very particular, one could argue masculine and Western, vision physics only further symbolizes the problem I am grappling with. Despite years of mentoring experience and my having been something of a leader in many mentoring efforts within my past department, this feels like a brand-new challenge. However, what gives me the most hope and energy is that while I am preparing to take it on, I have been able to practice what I want to preach. I have been inspired by some of my Access Network colleagues that have found ways to teach physics in a manner that is more authentic, equitable and inclusive. I have gotten advice, tips and encouragement from past coworkers and future ones. I have been able to rely on communities I have invested in time and emotion into over the years in moments where it felt like collective wisdom will surpass my own (which is very limited). I am not saying my class won’t be a mess, but it will certainly be less of mess due to folks that have very little in common with the cold absolutists I have encountered in textbooks.

Best,

Karmela

*In mathematics, the absolute value of a real number is its magnitude or “size” regardless of the sign. For instance, negative three and three both have the same absolute value (equal to three). The absolute value is a simpler equivalent of what may be called magnitude for a vector or a tensor – a quantity that has more than one component and has to be represented by more than one dimension. For instance, if one imagines a vector as an arrow in two-dimensions, its magnitude is equal to the length of that arrow. The absolute value of a real number is a similar measurement, but for a single number that is essentially a one-dimensional quantity or a point.

Programming note: Ultracold now includes a paid subscriber option. All future letters will remain free, but if you want to offer small financial support for the writing that happens in this space, you can click the button below.

A monthly subscriptions costs 8$ while subscribing for a whole year costs 90$. Most of my letters are longer than 5000 words which makes for at least 15,000 – 20,000 words monthly. Clearly, a monthly subscription makes for way, way less than a dollar a word. Of course, I am not comparing these essays to the kind of work I may be able to sell to a magazine at a dollar a word, and I love writing these letters more. Whether I have many paid subscribers or none at all really does not make a difference for my desire to keep writing them. However, what you get in your inbox as a subscriber of any sort is a product of labor and you can click below if you want to acknowledge that past being a reader which I do appreciate an awful lot to begin with.

ABOUT ME LATELY

WRITING A story of mine ran on the Scientific American website a few days ago and I am elated to have seen it go from a pitch to a commission to a published piece. The study I have written about, connecting statistical mechanics and concepts from out-of-equilibrium physics to composed music, caught my eye while I was looking for something else in a Physics Review journal and I pitched to Scientific American only because I thought it was very cool and creative. Luckily, my editor was equally intrigued ad it was really fun to dive deeper into the subject and get to talk to quite a few other scientists that also thought the whole thing was fascinating. I really hope I’ll have the opportunity to write more of these in the future.

LEARNING My husband got whisked away on a small vacation with friends from graduate school at the end of last week and through the weekend which resulted in me taking a pilgrimage to a vegan deli in Bushwick for half of one day and spending the rest of my solo days in a writing and planning frenzy.

Through the process of writing for Scientific American, I learned that I really like having an editor. Having my writing taken a part in a way that feels productive was intimidating, but I could see how it made my work better and felt challenged to grow. A few days of back-and-forth on a little under 1000 words taught me an awful lot on what I can do and what I still need to learn to do. I did do some panic baking simultaneously with filing my last set of revisions before the article actually ran, but at the end I mostly felt energized to try again soon.

When it comes to planning my course, I have been in something of an opposite situation since I have a lot more freedom than I have guidelines. I am sure there are parts of the schedule (that has to be appropriate for both a blend of in-person and remote learning and full-on remote only instruction if something goes wrong) that I spent too much time thinking about and some that I can’t quite see the importance of yet. Having just completed all of the lectures, assignments and activity worksheets for Week 1, I am sure the same applies to my treatment of subject matter and my design of problems. Teaching in this way and under these chaotic global circumstances is bound to be a trial by fire and whatever I think I am learning now probably cannot compare to what I will be learning in a month or two. I am still optimistic, however, even with the familiar fear of running out of time creeping into my days. I think I just might have no other options than to learn how to stick with optimism going forward.

LISTENING Poet Marilyn Nelson on On Being discussing poetry as a communal effort, poetry as an escape deeper into ourselves and poetry as a gateway into finding inner silence under the noise of the outside world. It all sounds cliché, but sometimes clichés are very fulfilling.

All of Music Exists on The Ringer podcast network which I enjoyed more than I expected. I consume a fair amount of audio content from The Ringer (owned by Spotify), partly for insightful criticism, but to a large extent also because many of the podcast hosts on this network are something like industry insiders and have access to knowledge that surpasses just talking about whether a piece of media is interesting or well-made. I appreciate this context as much as I do the fairly uncensored banter that is quite strong across the music, film and TV shows The Ringer produces. This podcast, however, was a little less loud and a bit more personal while also tackling some large questions about music as a cultural phenomenon (How does criticism change our perception of music? Why do we go to live shows? What does it mean for a song to be heavy? What do someone’s fans say about their artistic output? What did rock’n’roll do for our culture and society?) which made it engaging and relatable. In its best episodes it reminded me of Supercontext, and not just because co-host Chris Ryan likes to talk about the Boston-area hardcore scene. At fifteen episodes, this is a worthwhile binge-listen.

Parallel Lines by Blondie because Debbie Harry’s singing makes me feel like being at all the summer New York parties that we are missing out on.

This Ash Borer record and my playlist of space-themed death, black and sludge metal. For the first time in a few weeks I have been in the mood for heavy, crashing, grinding music that makes your stomach bounce and your throat itch, and it’s been very enjoyable to revisit that world.

READING Raechel Anne Jolie on love and pleasure activism during the pandemic in one of her recent radical love letters. I have come to really appreciate her writing. She is clear, direct and unwavering in her politics, but also rather tender and thoughtful, and this letter is not an exception. She writes:

“Just as my queer elders didn’t, I’m not suggesting we move forward with a reckless disregard for human life. As a Leftist, I see it as part of my raison d’etre to care most about the people for whom our system cares the least, and that’s many people who will be hardest hit by Covid: incarcerated people, immunocompromised people, houseless folks, and the elderly. Still though, it behooves us to pause when we are told that protecting human life must simultaneously uphold systems that harm us. (This, of course, is not so different from arguments we hear about the police.) And we might also want to give pause at abstinence-like models of remedy. And we have to think critically when the onus of stopping a pandemic falls to individuals and their actions rather than structural forms of care and support. In acknowledging this, we have the opportunity to find nuance that I think could be life-saving as we move into another month of Covid times. ”

And, later,

“How can we make life-enriching things accessible to people during Covid, and also remember this as a model toward more inclusive spaces for our immunocompromised comrades, even after the pandemic has passed? How can we continue to fight for a world that provides us the means to stay safer, like paid time away from unnecessary work and a health care system that actually serves everyone?

Can we keep each other safe and also keep joy alive? Can we both make responsible individual decisions that protect the most vulnerable among us, and also direct our ire toward the State rather than toward our friends who have decided to consensually hang out with other friends without masks? ”

This letter in particular has been a potent reminder of how fortunate and privileged I am to be not only housed with my partner, but also to be in a legal partnership that the state (and capitalism) looks favorably upon.

This poem by Jose Olivarez in Sonia’s Poem of the Week that resonated with particular potency while my husband was briefly out of town. I was both reminded of how beautiful it can be to be alone and how much I don’t want us to be apart long-term ever again.

Finally, two years after I first bought two giant copies for me and my husband to lug around and read together, inspired partly by an episode of Supercontext and partly by my friend Lauren once including a Thomas Pynchon quote in her newsletter KFZ and me still thinking about it two days later, I got around reading the first twenty-something pages of Gravity’s Rainbow. I imagine finishing this book by the end of the year is a lofty goal, and I am not particularly interested in trying to say something new or profound about it, but I am going to give it my best shot.

WATCHING We finished watching the second season of What We Do in the Shadows. Though I enjoyed a lot of this season, and this show, I was slightly underwhelmed by its finale. If more episodes are released in the future, I’ll be quick to seek them out, but I do wonder whether the series has become a little too invested in its own worldbuilding. Watching it complete the arc it has been hinting at for a while, I missed some of the more dry and more simple humor that made it so refreshing in the first place.

My father-in-law started watching Halt and Catch Fire on one of the nights when we were all home and up late so we made it through three episodes together and got invested. A show about early days of computing is something that appeals to me, at least in theory. I have eyed this series before but, for one reason or another, never quite got around committing to it. Judging by the first three episodes it occupies some middle ground between emotionally heavy and overly aesthetic-focused prestige TV and your run-of-the-mill cable drama, which is not necessarily a bad thing. It is rife with tropes that I don’t love: an anachronistically punk coder girl who is very much not like the other girls and given a somewhat uncomfortable and unrealistic prodigy treatment, a craven executive who also happens to be a bisexual that uses sex as a cajole and manipulates his coworkers seemingly without as much as a smidgeon of guilt, a couple that settled for a marriage instead of living their engineering dreams and are now both suffocating slightly (and the wife’s talent is painfully unrecognized at every step of their partnership) and that guy who played an old rich Texan on Glow playing another old rich Texan. However, it is also these exact things that make Halt and Catch Fire dynamic and inro some visual equivalent of catchy (though the soundtrack shines through as well). The four seasons of this show will likely make for good I-guess-our-day-is-over watching so we’ll probably stick with it for a while. I’m not expecting to be wowed, but it will be an entertaining story to keep coming back to.

EATING A few team efforts with my husband helping with trying to make new dishes from South America: this empanada dough stuffed with creamy spiced black beans and corn, served alongside a big massaged kale and avocado salad, and the simplest arepas from the back of the masarepa package smothered with more creamy beans and corn (this time in an ancho chile sauce) then topped with roasted plantains, cilantro and parsley chopped and quickly marinated in red wine vinegar and garlic infused olive oil, and a good dash of mango and habanero hot sauce. We were not great with shaping either of the doughs, but tastes and textures delivered.

This marinated tofu, sort of feta-adjacent, recipe paired with a big salad heavy on fresh tomatoes, a good drizzle of thick espresso balsamic and some roasted beets dipped in hummus. Motivated by a similar desire to eat things that are cold and soft, but having a completely different flavor profile: this super simple cold silken tofu (I left out the bonito flakes to keep it vegan, and topped with a mix of chopped scallions, cilantro, lime juice, sesame oil and toasted sesame seeds instead) together with a sticky zucchini, shiitake mushroom and green bean stir fry and a pile of rice.

Another foray into Indian cooking with this moong dal recipe and this cauliflower fry (cutting down the amount of oil by about a half) which I again served with a pile of greens very simply dressed with lemon juice and black salt.

And a great Italian-style sandwich and an even more amazing vegan croissant from Seitan Rising, a vegan bakery and deli that opened this past week in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn. This is a small business owned by two queer women where everything, including vegan meat substitutes and all breads and pastries, is made from scratch. I was familiar with the owners from some of the pop-ups we’d occasionally check-out when visiting New York in the past and loved the idea of them getting to do their thing more permanently enough to brave an hour-long train ride to their new location. I sanitized my hands about a thousand times before getting to the shop but, in the end, it was great to leave our neighborhood for the first time in a while and the food floored me like it has in the past.

Finally, I tried to remake one of the signature snack cakes of one of my grandmas, a simple sweet batter made moist and tender by the addition of yogurt and studded with ripe stone fruits like plums and peaches, with vegan ingredients. The result was really good and uncannily close to the tastes and smells I remember so fondly which brought a lot of joy to me and everyone else in our household who suddenly had something sweet to incessantly snack on. I have made the recipe available to my paid subscribers earlier in the week.

Keep up the good work. You are obviously quite gifted and I will be promoting your content to my students moving forward. -bd