Thanks for reading my newsletter! All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on X, Instagram and Bluesky. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

Later this summer, I am hoping to run an extra edition of Ultracold answering some reader questions about physics, science writing and science journalism. If you have questions along those lines please email them to ultracold.newsletter@gmail.com

CARNOT’S THEOREM*

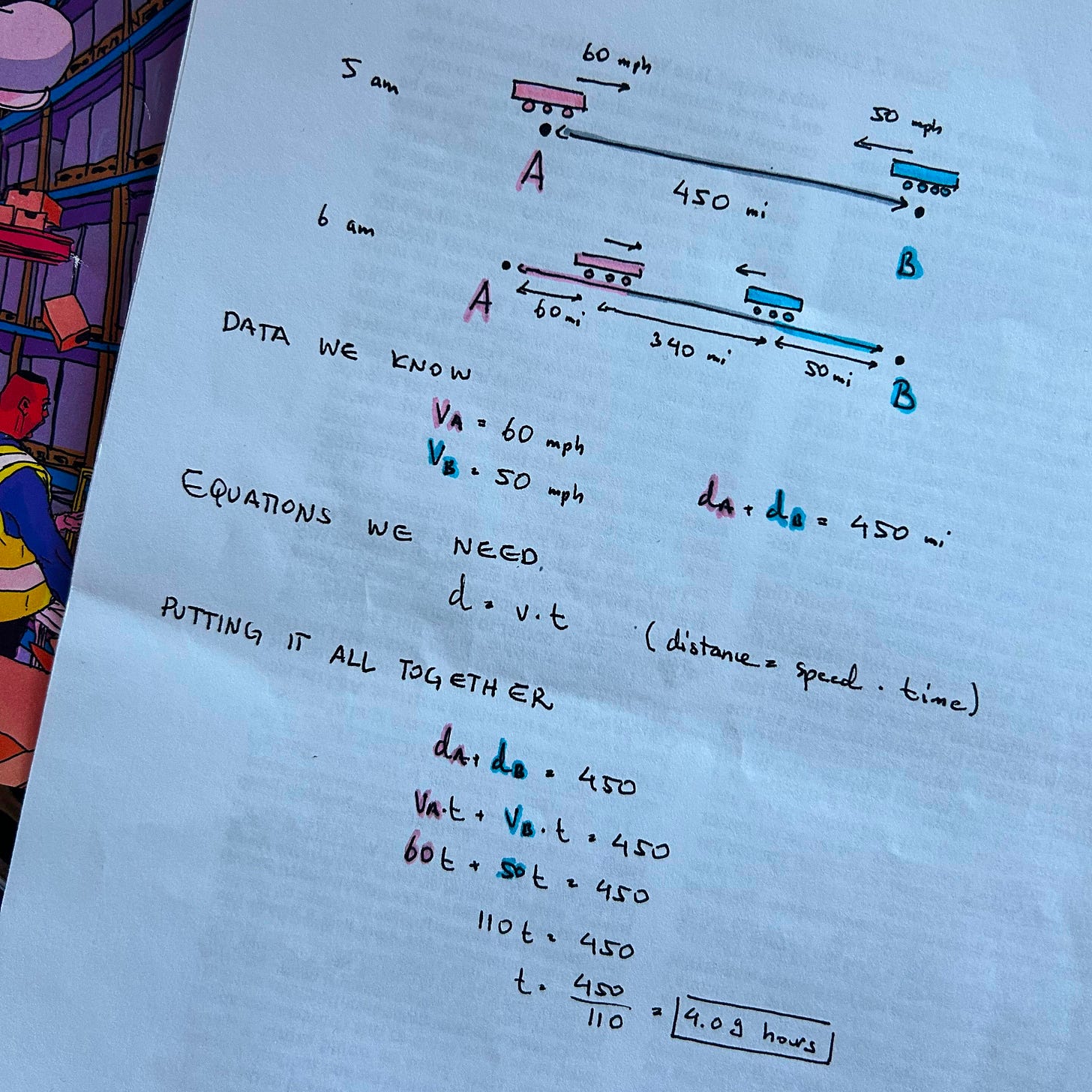

“Two trains are driving toward one another. At 5 am the first train leaves Station A traveling at the speed of 60 miles per hour to the East. At the same time, the second train leaves Station B, traveling 50 miles per hour to the West. The distance between station A and station B is 450 miles. At what time will the two trains pass each other?”

I could teach you how to solve this problem, I used to do it for a living.

First, you write down all the information, velocities in miles per hour and distances in miles, maybe you also draw a picture. Then, you need to either remember or find out from a textbook that distance is equal to velocity multiplied by time. This means that at any given time you can calculate where each of the trains is compared to the station it left. After one hour, for example, the first train is 60 miles to the East of station A because one hour multiplied by 60 miles per hour gives 60 miles. But you have one more piece of information: distances covered by each individual train have to add up to 450 miles or otherwise one of the trains would overshoot a station. Because you know to write distance as velocity multiplied by time, and you know each train’s velocity, this enables you to set up a one line equation where time “t” is the only symbol that you don’t have a number for. A few lines of algebra can now help you find this number and “solve for t.”

Students tend to dislike this sort of word problem until they learn how to break it down into steps. Once they do, they feel like they’ve been let in on some sort of a trick. And it always feels good to know what the trick is.

But what’s the trick when you’re on a train that’s suddenly making local stops or, worse yet, going express in some deeply puzzling sense of the word? What’s the trick when your M train unexpectedly turns into a J? When the G train becomes a shuttle bus? When you’re being momentarily held at the station because of a signaling issue, because someone on the train is unwell, because a station has mysteriously been shut down? What’s the trick when the voice that comes on from above to foretell and divine the faith of your commute sounds so distorted or so accented that you have absolutely no idea what’s going on and what if you actually had your headphones in and you were reading your book and now you have no idea what is going on and oh-my-god you are actually so not from New York City at all?

Look, I love this city. I’m not from here, but I want to be of here. I also know that what puts me through most tests as an aspiring New Yorker is the capriciousness of the city’s transit system.

In my first year of graduate school I resolved to stop running for buses and trains. I was too old for that now, and too serious, I told myself. The M train, which I now depend on to get to work three days a week, broke that resolve shamefully quickly. The hypothetical upper class cache of my PhD means nothing when I hear it rumble on the platform above the street and have to sprint up the station stairs. The train, and the city, do not care for my pride, my accomplishments or my self-made backstory. Even on days when I feel like I might be somebody after all, I still have to run for the train.

***

The train platform that I find myself reluctantly running to is unusually wide because the station closest to my home serviced a streetcar before it started servicing a subway line. The M train itself also went through a number of transformations. Its current route is closer to what used to be the V train than what was first designated as the M line in the 1960s. In 2010, the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) board members decided that riders had more affection for the M than the V so they only kept the former.

A dedicated subway blog put it less poetically: “The only reason the Orange M was created (and the combined route was not named the V train as an extension to this longer route) was to please local politicians, who didn’t want to remove the history of the M train as the subway route along Myrtle Avenue … the V train had no nostalgia.” The New York Times ran a cheeky headline “On The Subway, V Is For Vanished,” and that is exactly what happened. My partner says that he remembers the V train, which reminds me that parts of the city do not really vanish until they are also erased from everyone’s memory. It also reminds me that being from a place, and being shaped by it, often means being a chronicler of change, or loss.

As a relative newcomer, however, my memories of trains and neighborhoods that they serve are not tethered to their decades long history. When we lived in Williamsburg, I rode the L train, sometimes overlapping with grown up versions of people we called hipsters when I first started visiting New York in the 2010s. If any of them were getting sloppy at Union Pool back then, many now seemed to have somewhere to be at a respectable work hour, somewhere forgiving enough for a pair of Sambas but still demanding a nice shirt. On the early morning M train going from Queens into Manhattan I notice fashion trends less and people that look like my dad (Eastern European) or my nonna (on the way to a farmers market or a bank) more.

In other words, once our rent in Williamsburg rapidly rose to an unsustainable amount, we settled in a neighborhood where gentrification is creeping in rather than announcing itself with a gallop. We ride buses a lot more here, and the M is our only truly convenient train. Yet, much like every other part of the New York City subway, I’m always more grateful for the M train than I am annoyed by it.

Being able to live in a city where I could move around without the responsibility and risk associated with owning a car has always been an adulthood wish list item for me. The sense of the subway, and public transit in general, as a source of freedom is prevalent in how many people who grew up in the city speak about it too.

“For me, the subway was freedom. Being able to take the train to high school was a gift that opened the entire city, bringing me out of Brooklyn and to the Upper West Side and Greenwich Village, and bringing me together with classmates who came from all over the city, all five boroughs (yes, including Staten Island). The fantasy of the open road was nothing to me compared to the glories of the subway map,” wrote historian Kim Phillips-Fein in 2024. “You could do your homework or scrawl in a journal and then you could get out, anywhere you wanted, and simply be someplace new.” WNYC’s Brian Lehrer echoed the sentiment in describing his own teenage years in the city: “I felt a kind of freedom that suburban kids don’t have because I didn’t have to drive to be independently mobile.”

Unlike driving a car, which is a solitary activity for many working adults, riding trains is also inherently communal, even just as the most basic reminder that other people inhabit the city and move around it just like you. Whether you hate the closeness of bodies during rush hour or relish the opportunity for people watching, within the space of a train car it is hard to ignore the fact that to live in a city is to share space. I think of this in contrast to my mom driving to work and back every day and me sometimes riding home with her after school.

The car was our own little kingdom, or maybe she was the monarch and I an heir in waiting, both challenging the mores of her reign and learning how to eventually play her part. Whether we laughed or argue, the car’s interior was just for us and everyone else on the road was physically separate, walled off in their own metallic confinements. It was an “us vs. them” world by default, always a less collaborative effort than boarding a subway car. Because I left Croatia as a teenager, its car culture never got to me, and I have never had a drivers license. I have no aspiration to change that.

Because riding the train does not require the same kind of focus as driving a car does, a train ride can easily be spent reading a book, answering emails, resolving a lovers quarrel (or maybe starting one), revisiting a favorite record, crying because you’re sad, crying because you’re happy (a good subway cry is just underrated, a friend told me recently), learning the whole history of an ancient civilization from a podcast, discovering a new favorite song, or simply staring out the window and hoping that the moment when the train rises above the ground and the sun hits you will fix you a little. Whatever shade of self-reflection or self-maintenance you are looking for, a train ride can often provide a container for it.

Writing about train travel in Aeon in 2016 writer Margarita Gokun Silver posited that contemplation and travel are both means of constructing ourselves. Riding the subway offers daily chances for the two to intersect and intertwine. Each time the train doors open you have a chance to emerge somewhere new, as someone new. This process is not always positive - sometimes you really are stuck trying to maintain a coherent and self-contained sense of personhood on a train that is stalled, uncomfortable or shared with someone who is unwell or even hostile - but it is part of how the city forces you to be anything but static, to keep finding and expanding your edges. “A forgotten luxury in a society that moves with the speed of a viral post, this process of constituting ourselves has space to spark, germinate and unravel – only on a train,” writes Gokun Silver.

It is notable that public transit makes it nearly impossible to sever this germination from influences and presence of others. A seamless, frictionless world, the world promised to us by delivery apps, AI assistants and hyperindividualized hyperoptimized everything, is fundamentally at odds with riding the subway. It is a much needed source of friction, the kind that keeps us from becoming feckless automatons and forces us to continue being human.

On the first day of April I was on the M train early and I was tired and cold but next to me, a girl was curling her eyelashes. It made me think of reading Durga Chew-Bose years ago, while I lived in a small town where I refused to run for buses, there were no trains and I was always lonely. Chew-Bose wrote: “A woman on the C train pulling her ponytail through its tie, not once or twice, but six times. Six complete loops; her fingers closing into a claw each time. It'd been months since I'd been to a museum, but watching this woman mechanically tie her hair was softly enormous... Like Eastern Parkway on Labor Day; like Café Edison and Kim's before they were gone; like bodega cats and a bacon, egg, and cheese a woman grooming on her subway commute is a New York institution.”

From a quick, shy, sideways glance, I could tell the girl’s lashes were perfect. The iciness of the plastic and metal beneath me dissolved.

***

In addition to being main players in a myriad homework problems, trains played a significant role in the history of physics. The foundations of the theory of thermodynamics, which is the branch of physics that deals with energy, heat, temperature and entropy, were laid by the 18th century French engineer Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot, based on his studies of the steam engine. Though he subscribed to the “caloric theory,” which proposed that heat was a fluid and was discredited by the middle of 19th century, in trying to understand the sort of engines that powered trains and other machinery at the time Carnot seems to have glimpsed a deeper physical truth. Underneath an incorrect theory, he found the bones of a physical law that we still hold true today. Carnot was the first to identify what became the “second law of thermodynamics,” the famous one that tells you that entropy always increases.

One definition of entropy equates it to a measure of how disordered a system is, which makes the second law a favorite of poets and popular media. Carnot, however, was interested in more immediately practical matters. Thinking about an engine powered by hot steam, a machine that works because its temperature is being manipulated, he wanted to know whether any of its motions can be reversed without having to expend extra energy. Expending energy to reverse a process is not esoteric: a warm cup of tea will cool down without you having to do anything but if you want to warm it up again you have to put some energy into it. Carnot worked out that any process that increases entropy is not reversible ‘for free.’ Based on this, his eponymous theorem puts limits on the efficiency of any existing heat engine.

In 1927, British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington also used this line of reasoning about ever increasing entropy to define the “arrow of time.” His idea was that the cold tea is always in the future compared to the warm cup that is squarely in the past, that you could tell apart future and past exactly by measuring entropy.

This wasn’t the last time that the physics of trains intersected with the physics of time. Albert Einstein used a thought experiment where a moving train car is hit by two lighting bolts in two different places to dramatically illuminate the concept of “relativity of simultaneity.” Here, a person standing on the platform and a person onboard the train disagree on whether the two strikes happened simultaneously - one says that they definitely did and one says that they definitely didn’t.

There is no universal truth that resolves this disagreement. This was actually Einstein’s punchline: you have to acknowledge that the two people disagree because they are in different reference frames, one which is moving and one which is not. The motion of the train here serves to reveal that physics does not prefer one frame, that it does not mandate one absolutely correct way to see events. Frequent train riders can get used to this, sometimes you can even recognize when you’re actually standing still and the feeling of motion is fully an illusion sparked by a nearby train moving instead. It is nearly impossible to completely ignore the issue of perspective when you are on the train, whether it be a matter of physics or a matter of being reminded of other people.

The increased prevalence and popularity of train travel also led to the establishment of time zones. Until the late 1800s, American cities set their clocks according to the Sun, which led to the existence of at least 144 different time zones. Because there was no coordination between them, train travelers could find themselves disoriented by arriving in one town at a time that was technically earlier than when they had left. To add some order into the whole thing and avoid this illusion of trains traveling backwards in time, in 1883 railroad companies adopted a system of four time zones, Eastern, Central, Mountain and Pacific time, which we still adhere to in the United States today.

This was not like Eddington’s philosophically tinted arrow of time, not something mysterious that urges us into the future, but the exact opposite - a reminder that we are willing to chunk up time whichever way makes industrialized life more seamless. Train travel played a direct role in conquering geographical frontiers, allowing commerce and industry to expand westward and intrude into and exploit territory previously only inhabited by Native nations. Indirectly it also gave people enough arrogance to think they can conquer and reign in time. It was a symbol of a kind of steam-powered techno optimism that echoes in today’s shiniest new pieces of tech.

Though train travel did standardize time in a practical sense, it could not conquer it emotionally. The difference between physical and psychological time really shines on the train where the same ride can feel instant on some days and as long as centuries on others. If too many riders listen to music without headphones on your car, you find yourself painfully aware of every second in-between stations. If you’re engrossed in a book or a conversation, the stations often fly by too quickly. Sometimes it really feels like the subway is pulling a trick on you. The M train is the only non-shuttle service that starts and ends in Queens and its two endpoint stations are less than 3 miles apart, which is the shortest such distance within the subway system. Of course, if you get on close to one of the route’s ends at the wrong time of day or simply in the wrong mood, that distance feels monumentally longer.

After a few years of riding the subway almost daily, my body has also become conditioned to stir at certain stations and alert me that either they meant something to me once or that they ought to mean something to me still. The timeline of many of my days is determined by train rides, and the map of the subway has quickly found overlap with the map of my memories in the city. I guess this is part of how you claim a city, or how it allows you into its story, your history just one small thread in the incredibly dense fabric of its reality. (When I talk to my best friend about this, they tell me about a high school boyfriend who prom-posed with a hand-drawn map of the New York City subway annotated with locations of all of their past dates.) If the end of every train ride is a chance to exit somewhere new and be someone new then the predictable timetable of a daily commute is a reliable reminder of how dynamic, how changing, how moving a person gets to be.

Being in motion confronts you with the passage of time and the fact that you are hurtling towards the future. The second law would say that that future is a high entropy state. You may choose to read that as a suggestion that the future will always be more messy, but there is a more nuanced definition of entropy that physicists use in their work. A system with high entropy is one where more things are likely to happen. It is disordered in a sense that you cannot easily discern some order, or some hierarchy of most likely to least likely options. In that sense, a reliable rumble along the arrow of time is a journey towards a state of being where more things can happen, where more things could be possible for you. Of course, many could be terrible, just like the subway can turn hostile, dangerous and unpleasant, especially for those who are visibly different from the ever-narrowing sense of “normal.” But many could also be great.

I was trying to listen to a poet talk about craft on a podcast but the noise of an incoming train drowned his voice, previously so sweet and conspiratorial in my ears. By the time the noise of the train subsided, a preacher that had claimed a corner of the station stopped preaching and broke into a song. Another train noisily covered up the fact that he was off key. I forgot about the poet and his discussion of line breaks and empty spaces. There was no empty space in this station, no breaks in the noise. I got overwhelmed. I got on the next train.

In the dirty train car door I could see a fuzzy reflection of my short hair, my track pants, the cake carrier I was holding the way you may hold a dumbbell before you execute a curl. The person looking back at me from the glass was smudgy at the edges, diffracted through grease and grime of the city’s endless hands, so I could tell myself that they resembled whoever I wanted. Briefly, I thought that I could glimpse the silhouette of my baby brother as a teen. This pleased me. He has become a man, but I have been flirting with boyhood. The passage of time has been serving us differently. Of course I would realize this on a moving train, I thought. I gave my reflection side eye.

I remembered the podcast. Now, the poet was saying something about the sentence as an embodiment of keeping time.

***

It is impossible to write about the New York City subway without having to write about failings of the city government, about the repeated crisis within the MTA, about perpetually rising fares, about the even more rapidly increasing number of police officers at every station, about how many of the residents of the best city in the world cannot afford to sleep anywhere other than train stations. In the same way that riding the subway is a source of small frictions that remind you that a seamless world would have to be one devoid of people, it can also be a source of big shocks and existential crises. It is difficult to pretend that we live in a world better, or more equitable, than the one we do live in when you travel the city by train.

Subway ridership has been on a decline for several years now with the lockdowns at the height of the pandemic and the shift to remote work being one obvious culprit. But even before that, fewer people were using the subway and city officials were blaming rideshare apps. I always wonder how many people that chose to call a car, something which has been shown to make traffic and pollution worse at least in Manhattan, count not having to mingle with people who cannot afford to do the same as a perk. Tellingly, after lockdown ended, disparities in subway ridership mapped neatly onto neighborhoods' income levels and reports showed that “ridership through early 2022 remained much higher (as a percentage of pre-COVID levels) in lower-income neighborhoods than it did in wealthier ones.”

The Community Service Society estimated that “a majority of low-income essential workers living in the outer boroughs depend on public transportation to reach their jobs,” with the percentage hovering around 60 per cent. Access to public transit is correlated to better access to economic opportunities and lower unemployment rates. Continued investment in public transit is an investment in equity and New York City’s transportation system also produces fewer greenhouse gasses than our buildings, which additionally makes investing in the subway a real environmental win.

Ironically, some of the biggest threats to the functionality of the subway are a consequence of climate change, such as flooding from torrential rains and the high temperatures that can have impacts as dire as making the metal in the train tracks expand and cause misalignment. In 2024, the MTA put out a climate resiliency plan to the tune of 6 billion dollars over the course of next ten years. But the agency is always in some sort of a financial crisis, or on the edge of one, and its funds always seem to be tied to programs, such as congestion pricing, that state and city politicians play with as if they didn’t affect people’s lives at all. There are contours of a familiar story here: the impacts of a changing climate slowly chip away at the prospects of a better life for those who are already having to fight the hardest for it, for those who cannot just call a car when their subway stop is flooded or their train unexpectedly late.

There’s an old episode of Broad City where one of the characters nannies a rich kid. “Oliver, we don’t talk about Uber down here,” she instructs him. I laughed at this in 2015, before I lived here, but now it just makes me anxious. I worry that the subway could face the same fate as public high schools: if the wealthy, and the aspirationally wealthy, stop using it, those in power will feel more emboldened to let it deteriorate into being less convenient and less useful. I don’t want to live in a city where everyone is an Oliver Uber-ing to a charter school, where socioeconomic divides just keep deepening.

I think about this often when I am in a subway station where there are no benches, or no bathrooms, where no accessibility improvements have been made, or when I am on the train without a single trash can but a lot of actual trash. I’ve often heard older New Yorkers argue that we cannot have nicer subways stations and more amenities because someone would certainly immediately abuse and ruin them. People who say these sorts of things typically have an image of what “someone” looks like but they do not want to help that person, they want to punish them and then hope the rest of us channel our anger towards them too.

I’m not so naïve as to argue that everyone who exists in the subway system is a perfectly behaved angel, but I guess I am naïve enough to think that social norms can be leveraged the other way - that if the subway was nicer and we all treated it as a nice place, and a place that is nice to be a part of, then it would be a bigger psychological lift to want to vandalize it. As my partner once pointed out after I vigorously complained about a perfectly well put together subway rider throwing orange peels on the floor, if you want to argue that the subway is only for dirty people who do dirty things and don’t deserve anything but fare hikes and police surveillance it’s a pretty good idea to not give them trash cans and see how long it takes until someone lets a peel drop by their feet. People forget to pay attention to social norms when you put them in a place that looks like it could never sustain them.

It is also worth explicitly saying that very often who people complain about when they complain about the subway is New York City’s unhoused residents. It is in itself shameful that anyone wants to talk about architectural interventions for keeping them out of the subway instead of talking about the housing crisis and the scarcity of social services, but this is a talking point that is ubiquitous from dinner tables to city government. A little over a week ago, Mayor Eric Adams invited city and state officials to ride the subway trains at night alongside outreach teams that as of recently have the power to commit people to institutions involuntarily. His plans for a safer subway have always relied on this patronizing, forceful approach, on assuring “paying passengers” that everything will be fine if we just remove enough people. This does not address the root causes of why people are sleeping on trains today, it just means that most of us will have one more excuse to never think about it.

Here, again, the subway system viscerally captures the city’s truth, just the side of it that is much more dark and complicated than simply saying that you can see all types of people coexisting on the train. Here, again, the subway is a source of friction, the kind that could lead to contemplation and change on a collective and systemic rather than individual level, if we want it to. Riding the train every day can be contemplative, it can be a source of freedom, a source of relief, a personal journey, a journey to a better future, and it has the potential to radicalize.

New York is currently gearing up for the Democratic primary for the upcoming mayoral election, and one of the most talked about ideas put forward by rising star Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani is making the city’s buses free. While many major media outlets have dismissed him as a radical (the New York Post loves to call him a “socialist”), his campaign has been incredibly effective at fundraising and getting regular New Yorkers to get involved. People are excited about the simple yet concrete ways in which city officials could make their lives better, like making public transportation more accessible. There’s a lot that recommends Mamdani, but I would guess that anyone who stood firmly behind a similar promise would galvanize New Yorkers who may have never considered themselves radical lefties before.

Given what passes as moderate in politics of present day America and how much the idea of what is normal and possible has been shaped by right wing rhetoric, maybe making some portions of public transit free really is a radical idea. Taking it seriously, however, is, I think, part of the trick to being of a city - not forgetting that as much as it shapes you, you should not relinquish your power in shaping it as well. The future the train takes you too is not just one dictated by the second law, it’s one that belongs to you and your fellow passengers. Say “Hi” if I happen to be one of them.

Best,

Karmela

lovely piece. i had this sort of anxious tic for years where i'd wake up right at chambers street to get off for high school, and even to this day, i feel a surge of "wake up, you're gonna miss your stop" when i get there