All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on Instagram, TikTok and Bluesky. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

Later this summer, I am hoping to run an extra edition of Ultracold answering some reader questions about physics, science writing and science journalism. If you have questions along those lines please email them to ultracold.newsletter@gmail.com

MEDIA/DIET JUNE 2025

Thanks for reading my newsletter! This is a monthly edition of Ultracold where I share informal thoughts on media and food that I have consumed recently. A more polished longform piece, the annual Pride letter, will run on the 23th.

MEDIA

Recently, I read Michelle de Kretser’s novel “Theory and Practice,” a short but rich text about things as complex as academia and racism and as relatable as youth and friendship. Told in first person, it purposely plays with the trope of women writers being asked whether their fiction is just thinly veiled autobiography. But de Krester’s narrator is also so blunt and so unabashed in her imperfections that the sense of intimacy that comes from reading this book effectively makes the question of whether the writer and the narrator are one and the same unimportant. Because of this, when the narrator first finds herself at a party filled with aspiring bohemians and young people who otherwise want to be the arbiters of not just cool but righteous and transgressive cool, I felt her sense of both defiance and caution very personally.

Sure, the spaces in which I have experienced this were not populated with 1980s pretend Marxists nor was so much parental wealth looming in the background, but trying to be cool, or at least stay cool, among a new crowd where everyones is somehow more alt than you was a staple of my early teenage years when I so badly wanted to fit in with the metalheads and the punks of Rijeka, Croatia. And before the slightly older boys who complained about how “everyone in this town says they like Iron Maiden and Metallica,” there was the original cool alt guy figure of my dad. Though he would have never had called himself a Marxist, which would have had a very different connotation in post-communist Croatia, his commitment to Italian and Belgian comic books, his collection of film magazines, and all the endless stories of crossing the border between Italy and once Yugoslavia to buy heavy metal records that the communist regime didn’t like, makes me think he would’ve not been too much of an oddball at some Croatian version of parties from “Theory and Practice.”

By the time I was teenaged enough for music fandom to become my whole identity, the 2000s were underway but my dad’s idea of what was subversive or alternative in culture had managed to not change from his own teens. It stood still while I was growing bigger, older and more curious. We were a party of two trying to negotiate whether bands and music genres that were so well established as to be considered legendary could still have a bite. Did being a fan of AC/DC or Deep Purple still mean something? In my dad’s view of the world, this was still the best way, and possibly the only correct way to reject mainstream culture. When I was 16 we both got a tattoo of Derek Riggs’s signature, the one made famous by being hidden in Iron Maiden album art. But strife was imminent.

Even the newer subgenres of metal bothered my dad. He could never truly get down with blastbeats or death metal singing, and drone and sludge metal fell squarely into the category of his gripes that went something like why-does-everyone-make-up-genre-names-now. When I saw Boris and Earth and Cult of Luna in Chicago, and later Sleep in New York, and was deeply excited about it, he liked that I was still going to metal shows, but this version of it was nothing more than a signifier of only an almost-familiar rebellion to him. I listened to plenty of death metal without my dad but he never thought me uncool for that because the lineage of that music rhymed with his sense of art that is worth being different for.

But there was a whole universe of bands that were simply out of the question. Most were fronted by gangly, skinny men with sadness in their eyes and an affect nowhere near as masculine as the greats of the British new wave of heavy metal. This is to say that I never really listened to Nirvana or Pearl Jam. And until a few weeks ago I knew exactly one song by Radiohead.

Radiohead has always been a project that opposes not just the trends of their time, but also whatever the nostalgia behind those trends is. In their early days the band was in conversation not only with contemporary Britpop, but also the cultural worship of the 1960s that those bands were engaged in. On their early records, they were honest and emotionally raw to the point of what would be called cringe today. They were also nerdy before being a nerd was cool, they were guys who wanted to go to college and took interest in niche exotic instruments and odd rhythms.

I grew up worshipping at the altar of Iron Maiden where rebellion meant big hair, tight pants, an interest in World War II, a shallow flirtation with the occult, and being scholarly meant maybe sometimes reading Frank Herbert’s Dune. I still love many of Iron Maiden’s records, but no matter how much I wanted them to be expansive intellectuals when I was 16, they really were not. Radiohead, who released In Rainbows around that time, would have probably been a better match for my own nerdy, sad, queer personality. But at the time it never even occurred to me that their music could be for me.

I was a metalhead styled after the 80s, not some cerebral intellectual - or so I told myself while jamming a copy of Werner Heisenberg’s Physics and Philosophy into my backpack alongside printouts of Iron Maiden lyrics and R. A. Salvatore paperbacks. Look, my dad never talked about Radiohead’s frontman Thom Yorke, but I know for a fact that he would have called him whiny. Could you ever really be cool, and cool in a dark and subversive and deep way, while also liking someone whiny? I heard Creep on the radio here and there, and that was enough for me.

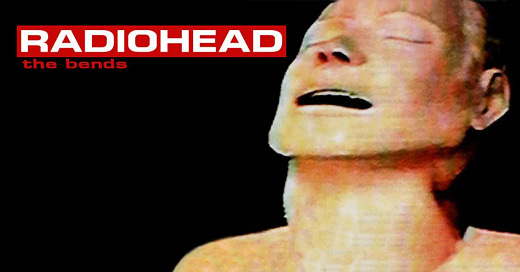

But a few weeks ago, one of my co-workers dropped the video for Just into a random Slack thread which spurred me to actually try to listen to The Bends, Radiohead’s sophomore album from 1995. And then I kept listening to it for the remainder of the work day, and then the next, and then the next, and so on, until it rang in my ears whenever I closed my eyes.

The strange thing about listening to The Bends thirty years after its release is that it immediately sounded familiar. This is because it has been tremendously influential. Coldplay, Muse, Snow Patrol and a dozen other bands were in the cultural aether, including the actual radio waves, when I was in my teens and twenties and they had all clearly never gotten over some of the quieter parts of The Bends. But The Bends also shares a surprising amount of DNA with records you may expect a traditional rock band to make. The main theme of the album is the band’s disillusionment with fame and disorientation at how fast they rose to prominence. What’s more rockstar than writing songs about how hard it is to be a rockstar? And there are some fairly legible sonic influences, like how Planet Telex occasionally reminds me of Pink Floyd, Bones has some U2 to it and My Iron Lung is clearly indebted to grunge in the best way possible.

Reading about The Bends, however, reveals that critics hear more than just strong rock roots in this record, so much so that writing about Radiohead seems to be its own genre of flowery language. The Bends is “fraught, compassionate, violently disturbed rock,” and “a melancholy hymnbook for alienated consumers,” while its songs are a“twisted pileup of grungy guitars and perky John Lennon verses” or “a panic-addled diary typed out on a computer screen.” The way people write about Radiohead reminded me of a scene where De Kretser’s narrator asks the man she’s having an affair with about what his girlfriend knows about them. He angrily retorts that they have a deconstructed relationship and the narrator comments “The calculated way he said ‘deconstructed’ amused me - he was producing the price of admission to the palace of cool. I remember him saying ‘bohemian’ with the same self-conscious air.” As the years went by, Radiohead became big enough to share another thing with the bands that my dad taught me to idolize - people not only started to love them but also to love talking about why they love them.

From all this commentary, all this critical baggage, you may think that listening to Radiohead with 2025 ears reveals a band that was always trying too hard, that The Bends would show some unseemly sense of the five skinny British men having done their homework and showing off their takes and notes. Except that by all accounts their recording process for The Bends was chaotic, it was unpleasant more than rehearsed. Studio executives doubted them, there was producer drama, there was in-fighting, and most stories of that time in the band’s history include unflattering accounts of Yorke if not severely depressed then at least habitually breaking down in tears.

In 1993 and 1994, Radiohead were not clueless and certainly not naive, but it is hard to believe that words like “hymnbook” would have been on their vision board. In subsequent years, Yorke always sounded annoyed at his perception as some sort of an anti-consumerist, alt prophet anyway. But if I had to guess what really motivates the press to write about The Bends in this flowery, gratuitous way, it is that regardless of how many years have passed, this album really does sound so very earnest. When Yorke sings “You'd kill yourself for recognition\ Kill yourself to never ever stop\ You broke another mirror\ You're turning into something you are not” on High and Dry or “I need to wash myself again\ To hide all the dirt and pain\ 'Cause I'd be scared\ That there's nothing underneath,” on the title track the way his emotionality resonates feels uncomfortably unrestrained.

I think this was also the sin that all the gangly, whiny frontman bands that my dad disliked kept committing. They did not shroud their feelings and opinions in sci-fi allergies or traditionally manly pursuits like, well, war or motorcycles. Their unhappiness and depression were clear, literal, audible, a rebellion not against some mainstream culture (because my dad came up in the 80s, he and his metalhead friends always positioned burgeoning Yugoslavian discotheque culture as their mainstream adversary) but against the idea that male rockers couldn’t sometimes actually just let their whine flag fly. The clash here is not just with the undercurrent of musical intellectualism in Radiohead, but also more basic notions of masculinity - and the way the two intertwine.

The more I kept falling down the Radiohead rabbit hole, and many of the records that succeeded the Bends really are replete with “Easter eggs” that you can just keep on reading about, the more I kept thinking about how relevant it feels to be thinking through this right now. I mean that in a very narrow, myopic, personal way in which I am more queer and more boyish these days so what masculinity means and can mean is top of mind for me, and I am a lot less committed to any fixed sense of cool. And I mean it in the sense of how mainstream culture, as much as any consensus about what that is exists anymore, is moving towards anti-intellectualism and the crudest version of what it traditionally means to be a man, especially for those men that want to have powerful platforms. It’s been a big year for cynicism, opportunism, and a whole swath of more horrifying -isms to such an extent that a little earnestness actually feels like a salve.

I was struck by this account of a 1994 interview with Yorke:

“I have a real problem with pop stars who work for charity, and say, ‘We’re gonna change the world,’” he says, dwelling on Live Aid-type fundraisers. “And places like Rwanda, where there’s a military government wiping out millions of people, where did they get the arms from? They got them from the West. We sell these poor little countries armaments, we make shitloads of money from them, they blow each other away, then we send them little bits of money to feed the starving. And I’ve never heard a pop star say, ‘Hang on, surely that’s what I should be writing about.’”

Watching the Live Aid DVD box set with my dad, all the many hours of it, was another staple of my teenage years, but it had always been a music event for me, we never talked about it as political in any way. My dad remembered watching it on TV contemporaneously and would talk about how amazingly large the crowds at Wembley stadium were. The rest of our discussion was being petty about the pop stars in the line-up. A take like Yorke’s would have rattled me back then. Now, it feels absolutely necessary.

And yet, Yorke publicly commented on the genocide in Gaza only very recently, with a lengthy statement that spends the first four or so paragraphs on how being criticised for staying silent on the issue affected him personally. The rest of the statement is not surprising nor is it all that radical. It may be braver than staying silent but not by much. There’s a disappointing flirtation with both-side-ism, there are more calls to not make assumptions about people who are not speaking up and more calls to not yell at famous people on the Internet.

Yorke has long resisted being put on any sort of pedestal, so maybe this is par for the course. Maybe this is the same self-centeredness that some found off-putting on The Bends. Maybe, to put it crudely, myopic whininess really has always been part of the project. Maybe righteous indignation and earnest rebellion just don’t age well, or at least not for anyone who does become a bona fide rockstar in the end, just like those guys that my dad liked. “I wanted to join the bourgeoisie and I wanted to destroy it,” says de Kretser’s narrator, who does become a successful, possibly famous, writer by the end of the book.

But I don’t want to end on a cynical note. The critics were right and The Bends is not a cynical record. There’s alienation and there’s pain on it, but its very last lyric is almost childishly positive: “Immerse your soul in love.” Radiohead may have changed since 1994, but I still think we may benefit from a little more earnestness, even if we have to find it elsewhere. The important part is, I think, to not forget to look for it as well as cultivate it in ourselves.

DIET

I meant to write this section about an almond and sour cherry cake that I keep baking for friends, moms and bake sales, but then I realized that I was eating a version of the same stewed mushroom dish for the fifth time this month and was still not sick of it. So, a few words on stewing mushrooms in a way that makes them amenable to being served over mashed potatoes, rice or on top of toast, after less than an hour on the stove.

Mushrooms are a popular substitute for meat in many restaurants that don’t necessarily specialize in meatless dishes or in those that do but without any particular cultural or philosophical focus (restaurants that use the label “vegan” as a way to not engage with their influences more explicitly). Often, this means that the act of substitution is not well thought out and the final dishes are not offensive, but not impressive either. Personally, I’ve rarely had a truly good portobello sandwich or “steak” and have been served many mushroom gravies that were mostly just grey or beige and salty.

Though mushrooms are not nutritionally similar to meat - a cup of portobello mushrooms does not contain more protein than a cup of broccoli - it is their soft-but-chewy texture that usually suggests them as a meat substitute. However, this is reductive as mushrooms come in all sorts of textures and the differences between maitake, enoki and shiitake mushrooms, for example, are significant enough that I don’t think all can be called “meaty” as a blanket term. If anything, “meaty” is a pretty non-descriptive word choice and does not lend itself to inspiration beyond naive imitation.

I thought about this whenever mushrooms showed up in our biweekly farmshare this past winter or when I grabbed them at an Asian supermarket where choices and prices are typically both stellar. When was I choosing to cook mushrooms because I wanted to taste mushrooms and when was I just chasing some other flavor, meaty or not, that they could be a vessel for?

Certainly, there are some winning ways of cooking mushrooms that are always worth returning too, like crisping up oyster mushrooms in a cast iron skillet, stir frying shiitake mushrooms with noodles or to serve over rice, shredding king oyster mushrooms and cooking them in a chipotle sauce for tacos or burritos, or taking the time to turn lion’s mane mushrooms into seafood-inspired patties. I do also really like a miso mushroom gravy, ideally heavy on rosemary, and crispy breaded maitake, like JJ’s Southern Vegan used to serve, do make for a fantastic sandwich. These dishes fall on the spectrum from “truly mushroom” to “kinda flavor vessel” and trying to place them within this gradient has generally helped me hone in on what about the dish actually makes it good - and needs to be turned up. Stewing mushrooms in red wine, as I have been doing a lot recently, splits the difference between my nostalgia for my family’s stews and how much I like the actual taste of shiitakes, king oyster and the like.

Because there have long been hunters in my family, the flavor of game stewed with lots of onions and a spicy red wine is as integral to my sense of taste as the fact that I grew up on the coast where fishing was ever present and that I hand picked vegetables from my nonno’s garden for as long as I can remember. Making a stew is as nostalgic to me as slicing a really good heirloom tomato and I rarely do it according to a recipe. It’s a dish that comes together through a confluence of memory, intuition, and whatever mushrooms I have at home have to offer.

My nonna or my dad would always start by searing the meat first then taking it out of the pan and piling on onions, but when I cook mushrooms, especially on a weeknight, I start by sauteing mushrooms and onions together, typically in a neutral oil such as canola. Searing the mushrooms first would add to their texture, but because they are not fatty like beef or venison, that would not impart flavor to the onions in the same way cooking them in a meaty pan does, and I find that the mushroom texture also benefits from more time in the heat. Shiitake are great for this, either sliced or whole caps, as are sliced king oyster or baby bella.

When I watched family members make stews as a kid, they would always dice their onions pretty finely but I tend to cut them into very thin half moons instead. Sometimes, I throw in some scallions as well. In addition to mushrooms, I usually also add cubed tofu or halved tofu puffs or seitan of some sort, to make the dish more nutritionally balanced and filling. Roughly, for two people and some leftovers, I use about half a pound of mushrooms, half a block of tofu (6 ounces or 170 grams), and 3-4 medium-sized onions. This is a very forgiving recipe and I am always mostly just feeling and tasting my way through it.

Once the mushrooms have started to sweat a little and the onions have turned a little translucent and a little golden, I add a few crushed cloves of garlic and then, after a few minutes, a generous splash of red wine. Ideally, enough to cover the mushrooms and onions about halfway. At this point, I turn up the heat and let the wine cook off so that some of its bite remains, but not the alcohol. If I can, I buy Croatian wine, like Plavac, which is rich in tannins and tastes like spices and sour cherries instead of being sweet. I like this dish to taste like mushrooms and be imbued with some of their own umami, but I am also a fan of layering different savory flavors so I typically also reach for a tiny bit of dark soy sauce or a slightly less tiny bit of tamari. Tomato paste is another way to add umami, ideally the kind that is very concentrated but not very acidic.

The other two additions are purely out of my family’s playbook: a few bay leaves and a tablespoon or two of plum butter. Bay leaves are just abundant on laurel bushes that grow all over the Croatian coast, and my nonna makes plum butter every year so it is no wonder that these are staples, in addition to pairing well with other strong flavors in the dish. I’ve never really left bay leaves out of this, but I have improvised lots when it comes to plum butter. Maple syrup works well, as do a few chopped up dates or, in cases of real pantry emergency, a bit of balsamic vinegar and brown sugar. Plum butter adds a sweetness that is more deep than cloying, so that’s what I look for when I am trying to use something else in its place.

I let the mushrooms, the bay leaves, the wine and all the seasoning simmer until I like the texture of the mushrooms and the tofu or seitan has absorbed some of the liquid. Whenever it all starts to look too dry, I add a bit of hot water or warmed up vegetable stock, all the while tasting to see if any spices need to be adjusted. I try to be judicious with salt and only add it at the end if necessary. A little bit of black pepper can also be nice.

On a good day, when my chopping speed is not terrible, this is a stew that makes it to the table in at most 45 minutes. I would never call it meaty, but it is savory and rich and full of texture in a way that is never not satisfying. When you bite into a mushroom, its flavor has not been fully obliterated, but it has also taken on some of the other flavors, striking a perfect balance between being a background player and the star of the show.

This was interesting - ‘I grew up worshipping at the altar of Iron Maiden’ - and when I thought about it more I think, Croatia. But then that is my projection.

Your deep dive into Radiohead and The Bends, the whole story you tell, is fascinating. I love hearing such reflections and close listenings to an artist and their music, especially a particular album (or even a song), when it comes to you years down the road, with new (you now, you then) eyes and ears.

For me, a similar artist/album experience would be John Coltrane, A Love Supreme, which I first truly listened to (vs ‘kind of knowing about’), with my mind then blown, only in my mid-30s, some 20 years after it was released and only bc I read something that said ‘listen!’, made me stop everything right then. I was just getting into bebop (Charley Parker!), after growing up on rock and at that time in life playing in a band where ‘new wave’ (Talking Heads! Blondie, Elvis) was our passion, but that album was a ‘free jazz’ adventure, and seemed quite intimidating lol.

Anyway, will now listen to The Bends. Maybe I will be inspired, having never been a big Radiohead fan (but just had to buy the OK Computer CD when it was released bc of all the excitement around me). Thx for all this, Karmela.

One of the things that was bracing about "The Bends" in 1995 (I was a junior in high school) is that Radiohead seemed like a novelty band or a one-hit wonder, or at least like one of the many bands that got a post-Nirvana record contract and would make one album before everybody stopped giving a shit about them. And it was just *so much better* than anyone had any right to expect. I remember my gothiest friend, at the time, told me that she was going to put a bunch of the songs on it on a mixtape she was making me, and I thought "the 'Creep' guys?" Like, I wouldn't have thought to buy their second album any more than I would have bought a second Spacehog album. And then I heard the songs!!!! Holy shit. They seem simplistic only in light of what Radiohead went on to do; at the time they were more emotionally and musically interesting than anything I was hearing on the radio.