Probability Density

On being trans in 2025

Thanks for reading my newsletter! All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on X, Instagram and Bluesky. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

This Pride month, please consider donating to an organization such as the Trans Youth Emergency Project, the Transgender Law Center or the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, or directly, materially supporting a trans person in your community.

PROBABILITY DENSITY*

In the days after the 2024 election I felt more fear than I ever have since being granted my first student visa in 2008. Then, fear turned into grief. Beyond the fear for my livelihood as an immigrant, I felt like my options for who I could become as a queer person, as a trans nonbinary person, had shrunk in one quick moment, without much deliberation.

I told myself to stop being such a fatalist, but the seed of it stayed put at the bottom of my stomach, occasionally blossoming into a tightness in my chest. Two months later, an executive order defined gender in a way that rendered people like me non-existent. Who I can be wasn’t just to be constrained but rather who I know myself to already be was to be eliminated from all records, from all life that is seen, supported and dictated by the state. As I was finishing this essay, the United States Supreme Court upheld a ban on puberty blockers and hormone therapy for minors in United States v. Skrmetti, a decision that effectively aims to prevent transgender youth from growing up into transgender adults. Another wave of grief washed over me, more devastating now that it wasn’t about me and my inner monologue. I could talk myself into being more resilient and tough, but young people should get a chance at a life where that is not their only option.

Throughout this year, privately, non-queer people in my life have been telling me that I was smart to have never changed the gender marker on any of my documents or anything permanent or official like that. They checked in and offered sympathy. I felt that I had to be grateful, they were well-meaning neighbors bringing me the emotional equivalent of a beige casserole. Most privately, to myself, I admitted that part of what I was mourning was not just legal recognition but also the possibility of exploring parts of medical transition. I’d long been scared to admit this to myself, but now the sense of impending scarcity and danger made it unavoidable.

“It’s like an intrusive thought,” I told my best friend about thinking about hormone replacement therapy (HRT) as we were making an “in and out” list for the year back in January, giggling like teenagers. Living in the bubble that I live in, I talked about it to my barber and a tarot reader at my yoga studio. There was no resolution, but I felt somewhat soothed just by having been heard. “You have to do this on your own terms, at your own time,” everyone said and I tried my best to not feel like both terms and time were slipping out of my grasp. I made an effort to replace grief with a realistic assessment of my privileges. I live in New York, I have health insurance, I could still try a little T if I wanted to, if I felt that it would actually align my body with the rest of me in a true and necessary way.

The Earth kept spinning around itself, and politicians of all stripes kept using trans people to spin whatever hateful narrative suited them. Unease became part of the atmosphere. Yet, “We have always been here,” I was assured by Instagram carousels. And I knew it was true.

My queer and trans friends were still there too, still down to play board games and cook dinner and exchange memes about deep sea fish during long work days. This state of juxtaposition between love and fear, between care and intimidation, between faith in history and distrust of the future, became our reality. The horrors of the macro scale, be it planet-wide environmental destruction and man-made climate change or the genocide in Gaza, did not completely stop joy from popping up its head on smaller scales, like picnic blankets and dinner tables. There is hope in that, but also guilt and a type of incoherence - in what kind of world can I be so cozily eating bread with a friend while people in Gaza are killed while waiting in line for food aid - that simply breaks a heart. It’s Pride month now, and that heartbreak is still with me.

Over the years I have written lots about physics and queerness and how studying one and experiencing the other has helped me make more sense of both. As I write in my upcoming book, Entangled States, I believe that the kind of questioning, reimagining and the continued state of (self) discovery that being queer makes if not natural then necessary, cannot be separated from the curiosity about the world that led me to become a physicist.

Writing after the queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz, who conceptualized queerness as “the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality,” physicist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein once noted that “queerness is conceptually always at the edge of knowledge.” The only other people who live at the edge of knowledge with so much fervor are scientists. I think of it is a tremendous privilege that I have found a way, and have been given at least some space, to be both.

Of course, everyone latches onto a metaphor that is closest to them or resides in a field of work that they know best. Because the world of academic physics that I have spent all my professional life connected to is teeming with people concerned with the nature of physical reality, finding hints of queerness there hit me extra hard. I could make peace with being something other than a woman who is just woman-ing incorrectly in part because I could tell myself that particles are a little nonbinary too.

In the quantum realm, every particle, such as an electron, is also a wave and every wave is also a particle. Stating it this way is actually an over-simplification: some physicists argue that we cannot actually know what an object is until we interact with it, that its state when left alone is a lot more fuzzy than what words like “and also” can capture. As a physics journalist I learned to use the phrase “cloud of potentiality” to describe this fuzziness, a statement of expansive possibility and becoming that has always resonated with me. Proper physics jargon is only slightly less poetic as physicists speak of “probability density.” Drawing this line between this and my personal sense of queerness as a state of becoming and potentiality has often given me the most fundamental sense of “we have always been here,” one as old as our universe.

A few weeks ago, I picked up a copy of Patricia Ononiwu Kaishan’s Forest Euphoria: The Abounding Queerness of Nature and gobbled it across a few days of reading whenever I could. It’s a gorgeous book that skillfully and artfully expands on what many queer people have come to learn over the years by themselves - that nature is all but strictly heterosexual and binary.

Ononiwu Kaishan speaks of nature with a deeply personal tenderness but she is also a scholar that can point to myriad examples of gender and sexual diversity among species of plants, animals and funga. With a focus on reclaiming creatures that mainstream culture never learned to see as cute, such as snakes and slugs, and a strong throughline of interdependence and flux, Forest Euphoria is not just a book that shouts out queer theory, but is replete with the practice of it on every page. Ononiwu Kaishan writes about intersectionality, interdependence and community as well as how politics and economics shaped the natural science in which she is well versed and which she practices as the curator of mycology at the New York State Museum.

A few pages into the introduction, writing about her love of snakes, Ononiwu Kaishan notes: “Their habitats were also my refuge; their complication of category - somewhere between earthly and demonic - needed no explanation to me, a child who found herself within the dysphoric double consciousness of an amphibious personhood. Together we could slither between the rocky contours of the world, both natural and imposed,” and that was enough to strike a chord with me in the same way that thinking about quantum particle does. Another reassuring reminder that what we call queerness has always existed, and has always been part of our world. Forest Euphoria generously offers many.

But as time goes on outside of moments when I read or spend time with my queer kin, and the world goes on unraveling, I am finding it harder and harder to ground myself in this way of thinking.

Uncertainty, for example, is also a staple of quantum physics. In fact, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which states that given specific experimental circumstances, some quantities can never be measured arbitrarily precisely, is one of the postulates on which the whole theory has been built. I’ve learned about it, I taught it, it comes up in my work as a reporter fairly often. In my calmer moments, I find thinking about it invigorating and generative.

Why do we think nature owes us certainty? What does it mean to define knowledge in a world where uncertainty is unavoidable? For the most part, I like these questions, and I like hearing about them from physicists, philosophers and whoever else will engage me on them. Yet, lately, the word uncertainty has crept into so much of the coverage of the world outside physics labs, of American politics and public life, and hearing it has made me feel agitated and anxious rather than inquisitive.

Another facet of the uncertainty principle, as Werner Heisenberg and his contemporaries formulated it in the 1920s and 1930s, is that it is about trade offs. You can measure one thing incredibly precisely at the cost of only being able to measure another very sloppily. Certainty is never free, and it only ever follows from action. The act of measurement is also central to quantum physics as the only guaranteed way to know an object’s truth is to interact with it.

You have to pick your best tools and engage the thing that you are trying to understand. Standing around and theorizing from afar is of limited use, maybe even limited value. In the quantum realm, if you hesitate, if you hedge, if you subscribe to half-measures rather than direct action, truths tend to stay out of your reach.

This Pride month I am feeling restless and impatient when it comes to both standing around and strategizing, and when it comes to accepting trade offs. As a friend recently told me, grief and anger can often mask each other, and seemingly suddenly some of my grief has transformed into an angry intolerance for stasis and lukewarm compromises.

Famously Pride was a protest, another slogan that has become a popular snippet to share on social media, a meme as much as a call to action. But I started writing this essay while residents of Los Angeles took to the streets to protect each other from ICE, and before I completed it millions marched in “No Kings” protests so I know protests are still possible. Acting instead of saying empty words is possible.

And if corporations ever tried to distract us by trying to rebrand Pride as a party, they seem to have abandoned those efforts this year. Despite some of the most currently up and coming pop stars building their whole aesthetic on efforts of trans artists, like Addison Rae and her stylist Dara Allen, seasonal items that corporations are offering the rest of us queers are not glam, they’re not slay, they’re just beige honey.

Corporations will always want our money, but it is as if they are trying to profit from the atmosphere of fear that the United States government is deeply invested in right now, as if they are trying to tell us that what we should be buying is props for laying low and avoiding attention. Whether you want Pride to be a protest or a party, this year it really will be a DIY project above all.

Writing about how she understands the word “queer,” Ononiwu Kaishan writes:

“Importantly, "queer" is a call to action, charging us to reject the many binaries that shape our current reality to the detriment of everyone. And while "queer" is used primarily to describe categories of sex and gender that are not considered "normal" in today's culture, the term can also be used more broadly for anything that complicates our ideas of what is "normal" versus what is "deviant." Queer theory asks: What has been categorized as normal, and why? How does the structure of our society—in the forms of race, gender, religion, orientation, ability, and even species-reinforce this categorization?”

This is an expansive reading of the word, and one rooted in politics more than in individualized markers of identity. It is the version of “queer” that appealed to me even when I was scared of words like “bisexual” and “nonbinary” and “trans.” It is also the version of queer that I hope those who want to think of themselves as allies to the queer community can sit with, adopt in the most radical way, and transform into tangible actions and material change. Sanitizing interactions with queerness, limiting its potential to personal preferences and aesthetic identity markers does not lead to change, it does not collapse uncertainties into truths. It only perpetuates the uncertainty, and only brings about fear and restlessness.

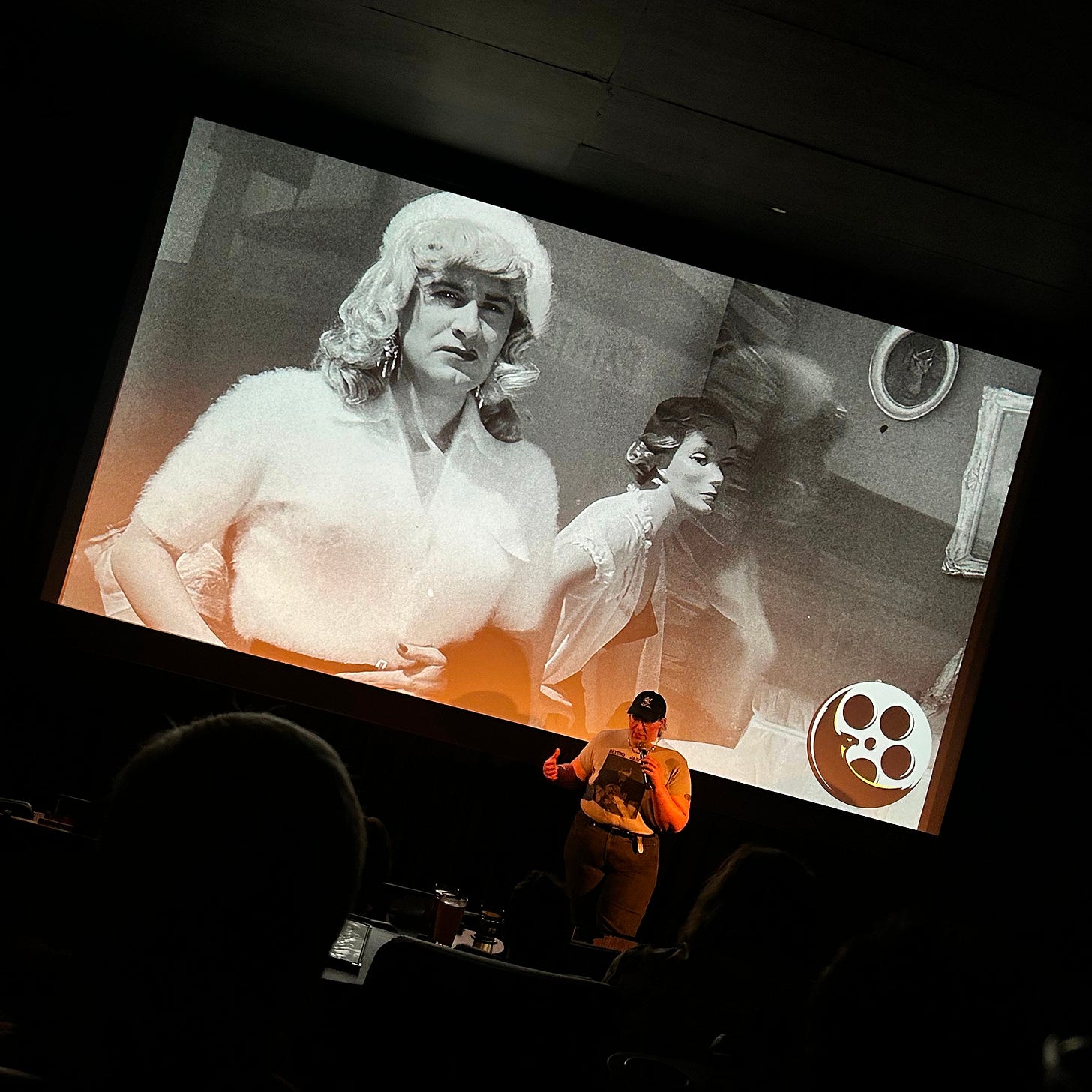

During the first week of June, I saw a screening of Ed Wood’s 1953 film Glen or Glenda, a movie which was commissioned as an exploitation flick inspired by the real life story of Christine Jorgensen’s transition but ended up something more like a cautiously sympathetic mockumentary, likely because Wood was known to cross-dress and may have had complicated feeling about his own gender. Though the film is often cited as the worst of all time, for me, the bad acting and cheap production did not take away from the fact that it is not outright cruel to transgendered people.

Certainly, Wood’s efforts to delineate between cross-dressing and being trans raises some complex questions as does the assertion that the former can be “cured” through therapy, but a portion of the film’s plot is set aside for a psychiatrist to recount a story of a trans woman named Anne for whom medical transition was an unequivocally correct thing to do and has led to a better life that the doctor character endorses. In fact, the story goes that studio executives found the film to not be exploitative enough so some versions include more explicit scenes that do not fit with the plot and were only cut in later.

Fairly early in the film, the narrator says: “Give this man satin undies, a dress, a sweater and a skirt, or even the lounging outfit he has on, and he's the happiest individual in the world. He can work better, think better, he can play better, and he can be more of a credit to his community and his government because he is happy.” I turned to my date and whispered “Is this the capitalist case for giving everyone free transition?” The joke may have been in a somewhat poor taste (I am not here to endorse a life centered on productivity), but this is the level of radical support that I wish I could see from self-identified allies going forward.

Instead of fighting tooth and nail for minimal freedoms on the back of poor faith rhetorical arguments about how few trans people are anyway, I want to see allies argue that, in fact, transition is not some last resort intervention for a depressed minority but a matter of bodily autonomy that everyone deserves access to. And I am not saying that trans and queer people need allies to save us, the historical record is clear on how we have resisted every attempt to be eliminated and erased, but a part of my restlessness lies exactly in the sense that being able to keep each other safe does not mean that we must let everyone else off the hook.

If we are to live in a society with some set structures of power, then people who have influence and possibility within those structures, and who want to be a force for the good, should be held to a high standard. The notion that our allies who have the most power in the government or mainstream culture are so lukewarm and so skittish that we will always do better by turning to our friends and other unofficial networks of support is another burden that is put on the trans community. In the long run we should all be hoping for a sea change, for nothing short of a revolution, and we should be working towards it. But in the meantime people who already have power and want to be the good guys do have a role to play - if they really are as good as they’d like to believe.

So many of the talking points that American right wing politicians are currently using to constrain the rights of women or destroy any semblance of affordable and equitable healthcare were first tested in anti-trans arguments, in framing the existence of a whole group of people as a grotesque political debate rather than someone’s actual reality. Had progressives, liberals and whoever else thinks of themselves as morally superior to the current regime in Washington been less worried about sounding radical and more cognizant of the fact that trans people are people too, maybe they could have at least slowed down the rhetoric that has now become policy.

Maybe they could have helped us understand concepts like bodily autonomy as a right, rather than something that even the most respectable cisgendered women increasingly have to fight for when it comes to pregnancy or birth control. As Andrea Long Chu wrote in New York Magazine, self-identified liberals are part of the problem, and they are part of the problem because their vision of liberty is informed and structured by the divisions of labor, power and resources that has already done so much damage to our planet and the people that inhabit it.

Chu skillfully identifies that liberals rarely object to the view of transgender people as either being delusional (so not really trans) or mentally ill (so being trans is a sickness.) “Every trans-identified person is either a participant in a craze or certifiably crazy,” she writes and notes how this opens the door for science, whether it be medical or psychological, to be used to wash the mainstream’s desire to keep the trans population small and pathologized. Skrmetti is a potent example of this as the arguments in the case portrayed medical transition as new and experimental, despite ample historical evidence to the contrary.

Moreover, argues Chu, it is not just that mainstream liberals get the ick from trans people or find the possibility of sex and gender not being strict, stable, unquestionable categories personally unmooring, but they on some level recognize that transness is a threat to the sexed division of labor that our society relies on. “I do not think it is an exaggeration to say that the anti-trans movement is driven by a deep, unconscious dread that society will not have enough working female biology to support the deteriorating nuclear family — and, with it, the entire division of sex itself,” she writes. This underscores feminist ideas almost as old as feminism where the demand is that no-one’s sex be used to confine them into a specific labor role in an unequal society. Yet, how many modern, mainstream feminists are true allies to trans people?

This type of argument, a material investigation of sex and gender, is uncommon in American politics and public life. Writing like Chu’s is decried as radical and unpopular. Well-meaning politicians and other holders of power within our system don’t want to sound radical and unpopular. They don’t want to learn about organizing from queer movements from history, they don’t want to learn about mutual aid from sex workers, they don’t want to learn about resistance from any labor or protest movement that was not perfectly peaceful and led by an easily digestible charismatic figure. This constrains their knowledge base and toolbox of resistance tactics tremendously (Raechel Anne Jolie often writes about this much more eloquently than I can).

But our culture is becoming increasingly conservative and the appetite for rubbing shoulders with anyone who may be deemed not just radical but simply a little weird, a little odd like the snakes and slugs and bugs from Ononiwu Kaishan’s book, is in short supply. A Supreme Court justice recently confused a woman wearing a leather jacket in a children’s book for a sex worker, that’s really all you need to know about the cartoonishly puritanical view of who should be not even listened to but simply shown which is taking hold in the United States so remarkably quickly.

P. E. Moskowitz recently wrote about how this particular flavor of small c conservatism manifests at Pride itself, noting that “every June, thousands of young people chime in to say that gay pride parades are too vulgar, that kink should be shamed and kept private, and that kissing in public is a form of sexual harassment because the people around the smoochers did not consent to witnessing it.” Would-be allies need to work through their ick of being faced with something that is an alternative to their idea of “normal,” then use it as a jumping off point for standing in solidarity with the rest of us and working together on structural and material changes for everyone.

Until this happens, we can all bemoan how uncertain the times are, but that uncertainty will always get reduced into a more restricted and dehumanising way of living. The radical conservatives don’t care about being radical, and they are not just standing around and thinking. They are collapsing possibilities into particular outcomes and they are not shy about interacting with issues that may be seen as controversial. Notably, the budget reconciliation bill dubbed “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” which is a hallmark of the current president’s agenda and was passed in the U. S. House of Representatives on May 22nd prohibits the use of Medicaid funds for gender affirming care like HRT, puberty blockers and a whole slew of surgeries specifically for trans people.

Medical interventions like HRT for cisgendered women in menopause or puberty blockers for cisgendered children who are going through puberty too soon or too quickly will not be similarly banned. Explicitly, the point of the prohibition is not to protect citizens from dangerous medical procedure but simply to make it harder for anyone transgender to change their body according to their own wishes. In 2022, a report from the Williams Institute noted that over 250,000 transgender people are currently enrolled in Medicaid, a fact that in itself reflects the material impacts of being trans in a world that is hostile to trans people, including difficulty with finding employment with benefits or decent pay.

Republican legislators unabashedly champion bans on transgender healthcare, but where are their counterparts on the side that purports to advocate for those of us who were not born here, or are not straight, or don’t hate ourselves for being trans? Hey, I know this may sound crazy, but I’d really love to hear a politician say “doing what you want with your body because it's yours is a right, actually, go for it.” I’d love to see a platform built on the grounds of securing material conditions conducive to a high quality of life for everyone, whether that means access to medical transition, universal healthcare, free public transit, more parks and affordable local food, less pollution - or, really, all of the above and much more.

Of course, all of these things are connected, and the material reality of transition would be a less fraught issue if all those other factors were already taken care of. Unfortunately, this too sounds like a radical statement in American politics where the fear of being called a socialist or a Marxist always trumps the fear of being seen shaking hands with aspiring fascists. As trans historian extraordinaire Jules Gill-Peterson recently told WIRED about liberal politicians and activists: “They’d rather plug their ears than admit that health care is a material need. It’s not a slogan. It’s not, like, a thing you support in your heart. It’s an urgent, lifesaving need.”

I am not writing this essay to announce something grand about my own identity or what I think I want to do about it. This is not any sort of a coming out essay and it’s not one that I can wrap up with some climactic scene at the doctor’s office. There is nothing about how I am feeling or what I am doing right now that could be packaged into an Instagram carousel or an easily digestible anecdote about “trans joy.” The truth is, I am still trying to digest what I have learned about myself in the past several years and incubate the person I may become next. I can’t offer a neat, tidy or triumphant narrative; I don’t think that’s how being a person works, especially away from the internet and the creator economy.

Certainly, it is not how it works in this particular moment where any decision about changing my body is inextricably connected to thinking about my status as a foreigner caught in a years-long immigration process and my ability to access healthcare in a sustainable and affordable way even in my blue state. These are practical concerns, but there are also many more on the side of family, coworkers as well my own internal reckoning of where my desires come from (the old irrational fear that I am also either crazy or crazed) and how critically I should assess them (what does it say about my world that I can’t trust myself to know myself?). I am asking myself many questions that I do not yet know how to answer. In a different world, finding those answers could be invigorating. In this world, I continue to oscillate between fear, grief and defiance.

What I do know is that I don’t want to be a frog or an electron anymore. I want to let myself be more than a profound metaphor that still serves to dull the edge of the material truth of who I am. Certainly, many of my trans kin do not have the privilege of nebulously existing in the discourse in the same manner that I still can, and it is on me to be their ally as well.

Right before Pride started I saw the activist and artist Tourmaline read from her book Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson, the first biography of the legendary trans activist, at the Brooklyn Museum. Afterwards, in conversation with Phoebe Robinson, she spoke about the process of writing the book and what it meant to have it be published right now, amidst unfiltered hostility towards trans people. It was a moving conversation, gentle in its encouragement that none of us give up on dreaming of a better future alongside our community, and firm in asserting that we also have to honor our rage. But what most stuck out to me was the way Tourmaline spoke of Johnson’s death.

“She didn’t believe in a binary between life and death,” Tourmaline said. “For Marsha it was not life and death, it was life and life and life.”

I wrote this down in my notebook. That assertion that it really can be life, and life, and more life, felt like the most radical ask of all. And life is never actually a theoretical matter. It certainly wasn’t for Marsha P. Johnson, who worked tirelessly to keep her community housed and otherwise materially taken care of. It is worth not forgetting that history, and following suit.

Happy Pride,

Karmela