Thanks for reading my newsletter! The breakdown: first a personal essay, some of my recent writing, then some thoughts on the media that I am consuming and finally some vegan food and recipe recommendations. All opinions expressed here are strictly my own.

If you are here because you like my writing about science or my Instagrams about cooking, you may not be interested in every essay in this space, but please do stick around until I loop back to whatever it is that we have in common.

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

QUANTUM ENTANGLEMENT

Quantum entanglement is a metaphor for love that is so obvious that a writer should almost certainly avoid it. The idea of two inextricably connected bodies, a connection that survives even across a large distance, neatly invokes the idea of entanglement if you’re a physicist. Equally neatly, it invokes the idea of a secure, steady relationship if you happen to be in love, or yearning for it. Because it is so neat, the chances of overlooking some subtlety when drawing the analogy between the two seem sky high.

But I have been trained to see the world through the eyes of a physicist, and for the past decade I have also been unabashedly in love, so I cannot escape it.

***

There is no counterpart to quantum entanglement in the classical world, which is the world of large and warm objects that we experience and participate in. Classical objects can be connected, like being glued or tied together, and they can interact across distance by being affected by each other's fields, like electromagnetic fields that connect cellphones. You can certainly affect another body without having to touch it, like yelling and letting the molecules of air wave and collide into them with the power of your joy or anger. But entanglement is different.

When I was first taught quantum mechanics, some of the lessons were about the correct symbols for writing down an entangled state. Understanding symbols really matters when you are attempting to translate physical reality into mathematics. To add forces, for example, you’re still allowed to use a plus sign but the answer you get depends on whether you know what that plus sign means when taken out of the context of adding 3 red apples to a basket with 3 green apples and finding that you have 6 apples total. It may not work out that way with forces - if they’re equal but pointing in opposite directions the plus sign will take you to zero rather than double. You can take the plus sign and put it between two quantum states too, but that comes with another set of caveats. Here, you don’t end up with a number, but something both more rich and less informative.

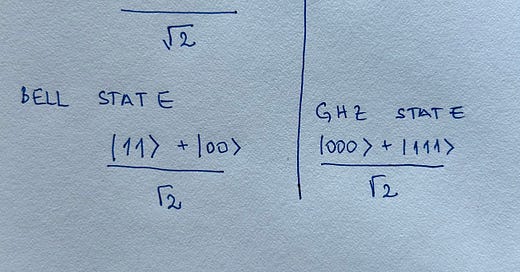

Each quantum state is a collection of properties, like which way an electron spins or what the wavelength of a chunk of light is. When you put a plus sign between two states you are expanding the number of possible properties a thing can have without really committing to any of them. Are your symbols standing in for an atom? You’ve just acknowledged that if you kick that atom or look at it with some instrument there are many options for what may happen next and the plus sign signals that sense of ‘more’. Consider the symbols below, with 0 and 1 being somewhat imperfect stand-ins for two different sets of properties.

For the gruesome example of Schrodinger’s cat, all qualities of being dead are flattened into the symbol 0 while 1 represents the cat being alive. You have a so-called superposition state which offers you options - if you do something to the state, like look at the metaphorical cat, you will either find it a lively 1 or a mournful 0. The plus signifies that the cat is multiple things at once, in multiple seemingly mutually exclusive states, until another party - you - enters the situation and interacts with it.

Entanglement suggests a different relationship between two objects, not so much that of a rich subject and an examiner who distills that richness into a single observation, as much as two connected entities on an equal footing.

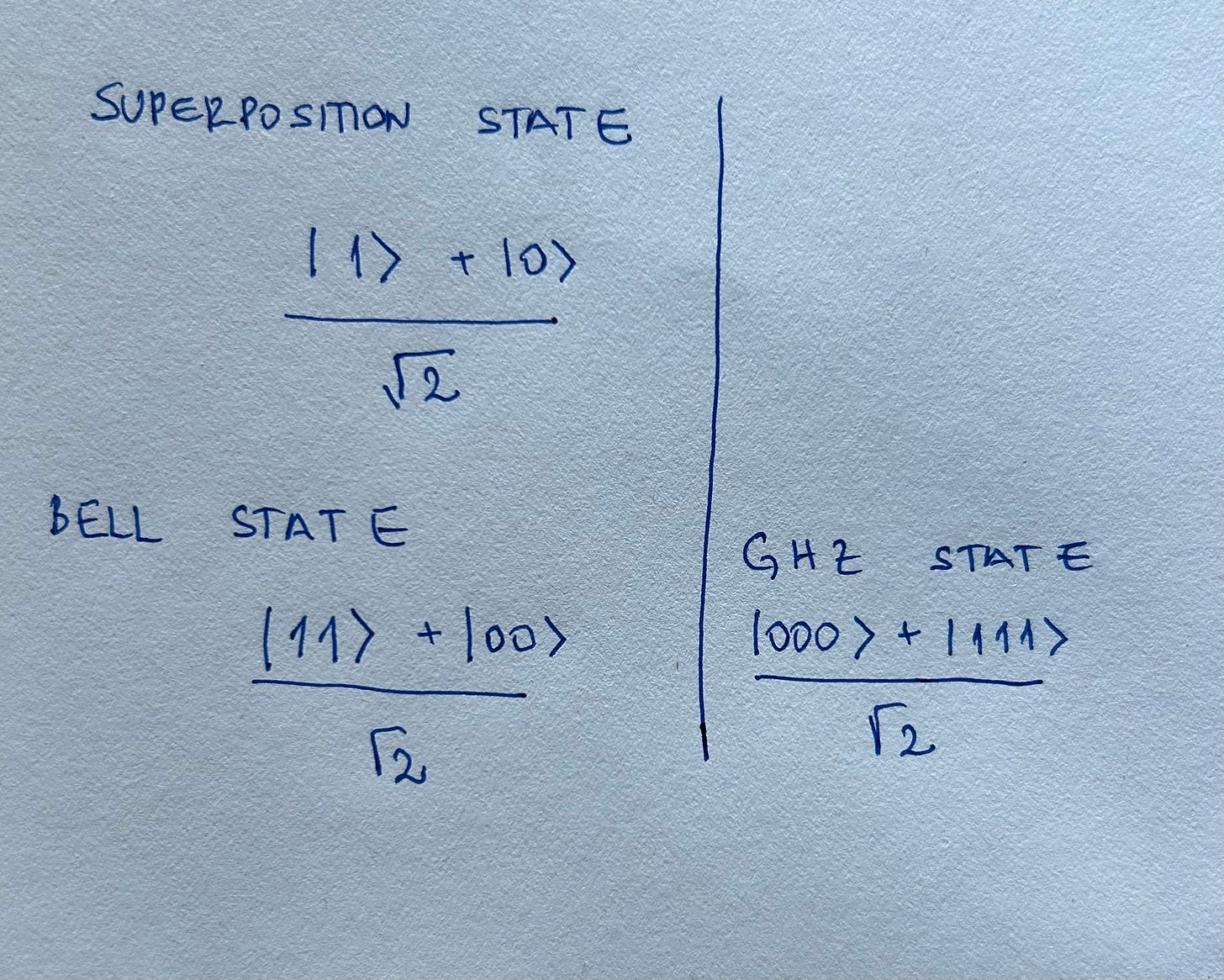

There are entangled states that are famous enough among physicists, mathematicians and experts on quantum computing that they have names, like Bell states, named after John Stewart Bell who had done foundational work towards experimentally proving that quantum mechanics, with all its oddities, does describe our world in the 1960s. In 2022, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger in part for experimentally validating Bell’s work by working with quantum light. One of these physicists features in the name of another famous entangled state, the GHZ state which has proven to be an integral ingredient for the quantum computers of the future.

Consider what the Bell state and a GHZ state look like within the same mathematical convention as above. The plus sign does show up again, but now the 1’s and the 0’s are never alone. Within the confines of their flat and kinky brackets, they cuddle another 1 or a 0, a shorthand for a set of qualities that belong to another that has somehow lost the independence that its own bracket would have afforded it. I am not going to ask you to imagine two entangled Schrodinger cats as I cannot bear the idea of both ever reaching the 0 state, the dead state, at once, but if you’re strong enough for that image, it would not be incorrect. Instead, consider the more impersonal case of two electrons where 0 and 1 indicate the direction of their spin, one being clockwise and the other counterclockwise.

Now, take the case of two 0s in one bracket with two 1s in another, connected with a plus sign. The plus sign is again here to tell you that the two electrons may be both spinning clockwise or both spinning counterclockwise and that you really have to interact with them to find out. But because they are entangled, their symbols cuddled up together, you get a break in just how much looking or measuring you have to do.

In the most extreme example, the two electrons are as far away from each other as the length of the universe and you only manage to examine one of them. If you find out that the electron on your side of the universe is spinning clockwise, without a doubt, even if you never ever manage to retrieve the other one, even if you never make a friend on the other side of the universe who could pick up some sort of cosmic phone and tell you what’s up with the other electron, you can be sure that that distant particle is always spinning clockwise too.

This is the crux of entanglement: one entangled object can never escape the correlation with its pair, it can never be ambivalent to its partner’s state. The states of the two, their material properties, and how they interact with the world are always inextricably linked. So, you can see the temptation of reading something sentimental and sweet into this situation.

Because this is a quantum phenomenon, it brings with it all the tensions around how quantum mechanics is interpreted. Physicists have been troubled by notions such as entanglement since the very inception of quantum mechanics. Lots of work has been produced thanks to that tension, including Bell’s work which, as we have now found, is not just meaningful for understanding how quantum our physical reality is but also useful for the-future-is-here kind of technologies like the unhackable quantum internet. Albert Einstein had thrown in his hat too, his “spooky action at a distance” objection to quantum physics, which is about entanglement, making it into the New York Times in 1935 under the somewhat hard to parse headline “EINSTEIN ATTACKS QUANTUM THEORY; Scientist and Two Colleagues Find It Is Not 'Complete' Even Though 'Correct.'” Making statements about what entanglement is or means is then fraught by default, even if your statements are mathematical and what physicists consider objective and rational, and not motivated by how big and soft your heart can feel day in and day out.

That headline from the Times offers a clue towards another tension in how physicists, and the spectators and commentators of the field, use their imagination when they interpret their work. Einstein’s attack on quantum theory hinges on a paradox called the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox, named as such because the famous physicist formulated it with two collaborators, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen. Because the culture of physics has long been shaped by narratives of lone geniuses and paradigms of singular great men, Podolsky and Rosen are made into the more anonymous “two colleagues”, inviting the reader, or maybe meeting the reader’s expectation, to focus on the most mythical of the group.

Collaborations like the one between Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen, whether they include thousands of physicists across institutions and countries like at CERN or just a few colleagues in their own academic bubble, are at the core of how physics is done today. Personal connections between physicists are also integral to how they find employment, start projects and share their work, and there is probably its own entanglement metaphor at play with how any researcher stays connected to the senior scientist that supervised their doctoral work (I will always and forever be identified by other physicists through my place in my advisor’s ‘family tree”.) Yet, the discipline clings to myths of meritocracy and self-made thinkers so much that all interpretations of what is found in the math and experiments are conveyed through cold and impersonal metaphors, or ones that hinge on shock like Schrodinger’s cat.

And as I buy my time on the way to committing to the metaphor that I opened this letter with, the one where being in love is like being quantum entangled, I can’t stop myself wondering whether what I am about to do does do the science a disservice. Regardless of my true belief in unlearning coldness and using rationality as a shield from how complex the world is, including its discomforting power structures, am I about to add fuel to an already troublesome heap of the word quantum being used to sell pseudoscience? Such misuses already range from harmful health claims, to fake psychics to dishonest consulting and coding businesses. In fact, misuses of “quantum” are so rampant and egregious that last year physicists Chris Ferrie had enough material to publish a book titled “Quantum Bullsh*t How to Ruin Your Life with Advice from Quantum Physics” which aims to dispel some of that nonsense. The claim that quantum mechanics is just perfectly cold and objective math is rooted in white, masculine, Western thought and can do us lots of disservice, but the flipside of it, the full boar commitment to turning it into something mystical, can be really harmful as well.

And so, the usual caveats. Most things you encounter in life will be too big and too warm to exhibit any sort of quantum behavior. For instance, the EPR paradox has been tested with a few hundred atoms a year or so ago and that was considered record breaking while your body contains something more like 7 billion billion billion atoms. In 2018, physicists broke the record for biggest objects that could be quantum entangled and they were roughly 20 micrometers in size each, which is approximately the same as the diameter of a single human hair. And you do actually use quantum physics an awful lot in your regular life, because the way electronics work in your phone and computer hinge on electrons being quantum entities - and that fact has not imbued you with psychic powers or an ability to teleport yourself like a quantum state can, and never will.

I have wanted to be a physicist since I was in the 7th grade, so much of my adult, and not so adult, life has seen me trying to learn how to think like a physicist. I talk about this all the time, about how being immersed in the science for so long and developing my sense of personhood alongside developing skills and practices necessary for being a physicist, changed the way I make sense of the world. Throughout all of the most chaotic, most confusing, most saddening and most disruptive times of my life, I have always found myself turning to an idea that came to me through the study of the physical world and finding solace and refuge in it, not as a distraction but as an assurance that physics is so rich and weird that I could never truly be that much of an outcast or an anomaly. This instinct has fueled many of these letters over the years, and it will be the backbone of my first book.

I have seen for myself, what a metaphor can do, or what can happen when seemingly disparate concepts are brought into contact, whether it be because they are parallel or stand to highlight the differences between each other. So, when I started reading physicists and feminist theorist Karen Barad’s “Meeting the Universe Halfway”, their critiques of using physics as an analogy stopped me in my tracks before I even finished the introduction. Barad writes:

“... if the goal is to think the social and the natural together, to take account of how both factors matter (not simply to recognize that they both do matter), then we need a method for theorizing the relationship between “the natural” and “the social” together without defining one against the other or holding either nature or culture as the fixed referent for understanding the other. What is needed is a diffraction apparatus to study these entanglements.”

And then, later, referring to the writings of one of the founders of quantum theory, Niels Bohr,

“According to Bohr, our ability to understand the physical world hinges on our recognizing that our knowledge-making practices, including the use and testing of scientific concepts, are material enactments that contribute to, and are a part of, the phenomena we describe.”

Within this perspective, an analogy will never go very far as it assumes that the things it is comparing are separate to begin with and unchanged by being connected, even just by theory, just by thought. In fact, Barad seems to discard the existence of things when they stand alone all together, turning to the neologism “intra-action” which, as they write, “signifies the mutual constitution of entangled agencies….the notion of intra-action recognizes that distinct agencies do not precede, but rather emerge through, their interactions.”

Barad’s book is rigorous and formal and dense, and I have not read a proper theoretical or philosophical text since college, so I am trudging through the ideas they pack into it slowly and carefully. The notion of things becoming what they are only through interacting, through being brought together in some way, and Barad’s own copious use of the word entanglement keeping sticking with me though. In my small narcissistic moments, they feel like they are pointedly prodding my own project of understanding how to exist in a physical world.

Has my training as a scientist in general, and a physicist in particular, given me more than analogies and metaphors? Have the intra-actions of my conception of self and my conception of an electron, of an entangled state, of a quantum chunk of light, or an atom being kept exceedingly cold, been what matters the most for how these words are making their way on the page right now, rather than some notion of a mind that I can even begin to keep separate? The romantic in me, the person that falls for every meme about myceliums and the magic of a tender, inter-connected life, would be perfectly happy to misinterpret Barad as saying that without my entanglements and interactions with others I am barely real.

The metaphor I wanted to start with, the one connecting quantum entanglement and being in love, at least deserves that I turn the order of connection-making the other way around. Maybe it is not that learning physics has made me compare entanglement to being in love, as much as being in love has made me see it in everything I encounter. And if immersing myself in physics for decades has changed the way I make sense of the world, then what has living a life filled with love done for that sense-making?

Recent years have brought me more grief than ever before and with that grief came lots of undoing, un-learning and unraveling that I can still feel loosening and tightening different knots of feeling and understanding within me. Some of it helped me let go of that cold person who strives for rational and objective understanding only and softened me to ways of approaching the world that may be less beholden to colonialism and whiteness than Western science is. Some of it opened me to more love, more being in love, more silly and hopeless infatuation, more deep adoration, and more security in the bonds that I had been forging for years. Like I wrote in September when my partner of nearly ten years and I celebrated another anniversary of our wedding, I say “I love you” to a lot of people these days and I am entangled to them by both choice and the incredible luck that allowed me to find a new sense of community even among some of the darkest times. Appropriately enough, not only is it possible to quantum entangle more than two objects, but multiply entangled states are often the ones with the richest physics, the ones that you want to create within your experiments and devices the most.

Whether the metaphor works or does not work, and whether I’ve escaped its pitfalls, may then not matter at all, because putting entanglement and love side-by-side imbues them with a different sense of reality, one that I want to keep existing in for the years to come.

I love you,

Karmela

Do you like Ultracold? Help me grow this newsletter by recommending it to a friend, sharing this letter on social media or becoming a subscriber.

ABOUT ME LATELY

WRITING

As a real milestone in a journey I’ve been on for almost two years, I was recently able to announce that I am writing a book, to be published by Beacon Press in 2025. Titled Entangled States: A Life According to Physics, it will be an exploration of how physics concepts and my life as a queer immigrant scientist and writer intersect, broken down in 12 chapters touching on everything from the arrow of time to path integrals to electron spin. The process of writing a book proposal and finding a publisher has been fairly harrowing and I lost faith in this project many times just to then fall back into it and fearfully try again. I am really lucky to have actually reached this current moment and still a little shocked that it actually happened. Writing Entangled States will almost certainly be the hardest thing I have ever done, but I also feel very deeply that it is something I want to and maybe even have to do. More than anything, however, I am grateful and I am especially grateful to all readers of this newsletter. Ultracold has been the place where I have done the most to find my voice, to build out my very small niche, and to allow myself to feel like a writer who just likes to write regardless of how they make their paycheck. If you have read more than a few of these missives in the last year or two, you have done more for me, and for Entangled States, than you probably know. Thank you!

At my day job at New Scientist, I was really excited to see my reporting on how ideas from physics like equilibrium and entropy connect to studies of what consciousness is included in a special issue of the magazine that focused on the brain. This story about a fundamentally new kind of cooling that does not require a refrigerator was also very interesting to pull together, especially because I had to translate a theory paper hinging on the mathematical concept of Hermiticity, not a word you’d use in everyday conversation, into something that makes sense to non-physicists.

READING

Before turning to Barad’s book, I read the short memoir Earlier by the music critic Sasha Frere-Jones. I have been a long time on-and-off reader of Frere-Jones’ newsletter and have encountered some great and challenging music thanks to his truly eclectic taste and incredible fluency in seemingly every genre. Earlier is a quick read, broken up into vignettes that rarely span more than a few pages, jumping back-and-forth in time in a way that fills in some parts of the critic’s life and leaves many intentionally empty. He writes of a New York that I only know from other stories and of bands whose names I recognize as iconic but have only engaged with shallowly, as happens when the moment passes you by. There is something very inviting in the simplicity and openness of the style in which Frere-Jones writes and something cautiously tender and optimistic even though he does also lay out a whole lot of heartbreak. This is probably a memoir with a fairly niche appeal, and probably would be boring to some, but it got me to listen to Sonic Youth and think about Brooklyn in the 80s while making my commute into the hellishly corporate hub of Midtown Manhattan and that was the kind of confluence that an over-thinker and a sentimentalist like me can enjoy.

LISTENING

My best friend got us tickets to see Mitski and though I had really liked The Land is Inhospitable and So Are We already, seeing her live really elevated the music for me. In anticipation of the show I took a bit of a dive into her past few records and found it really compelling, and then the theatricality of her performance, the precision of her movement and the more novel, folksier arrangements of songs pushed the experience way beyond my just liking the music. What impressed me most was how tight and well-planned the show felt with every little detail just right and perfectly in line with Mitski’s vision as an artist. Her voice and musicality were in themselves captivating, and her songs absolutely held up in a live performance, so much so that I went home and immediately started listening to them again.

At work, I have been listening to a lot of AI Lover and Jacco Gardner, both somewhat psychedelic, somewhat repetitive, on the edge of droning but in an invigorating way, types of musicians. I used to never listen to music of this sort but these days it is really getting me through marathon sessions of reading as many unpublished papers as I can, as quickly as I can, that my job regularly calls for.

WATCHING

My partner and I hosted a very small 1960s themed dinner party that culminated in a somewhat raucous communal watching of the 1962 film The Music Man. I am completely clueless about musicals so everything about this film was new to me, and much of it quite surprising. Later, we had a long discussion about whether the film was prescient about how people sometimes prefer to be entertained instead of facing the truth, about moral panics, and how much of it was meant to be taken tongue-in-cheek. While the songs may have not been the highlight for me, I really enjoyed that there was so much about The Music Man that we could discuss, and I was definitely not immune to its campy visuals and sharp caricatures of the Midwest.

We were also part of a very sweet pre-Valentine’s outing to see Lisa Frankenstein at the movie theater and had a much better time watching it than I anticipated based on the trailers. Written by Diablo Cody, this is a zany period piece about teenage angst, reanimated monsters, murder and romance across the veil. It is not particularly coherent nor offers any real depth of characters, but it is so campy, quippy and the bits follow each other in such fast succession that it was hard to dislike it. It’s a sort of a hybrid of Heathers and Clueless but for gen-Z fans of Riverdale, Cole Sprouse as the monster included, and queer folks of all ages, with a little less finesse than those two films and a whole lot of perfectly costumed, mildly manic energy.

Finally, we finished the second season of Good Omens on Amazon Prime, a show that I kept telling people I feel lukewarm about, and then also kept watching. This was an odd season in my view, with the main storyline much weaker than in the first season of the show and the relationship arc and relationship building between the two leads much, much stronger than before. In some way, I would have preferred a shorter and more compact show simply following the two characters ingeniously played by David Tenant and Michael Sheen both through historical flashbacks and present times with very little world building around them. The half-baked rehashing of some plot points from the first season and introduction of new, flat characters that are clearly just devices was just not compelling. I hope the writers of this show can strike more of a balance in season three. All criticisms aside, I did find John Hamm delightfully goofy, and the very emotional ending of the season did wreck me a little, probably just enough to keep me watching for another season.

EATING

A pineapple upside down cake adapted from my battered, thrifted copy of the Cake Bible. Veganizing it has been a bit of a work in progress, but it still got pretty good reviews after I served it with some milky vanilla frosting.

A sour stew with beans and black radishes, inspired by my grandma’s “repa i fazol” because these days my homesickness lives only on my tongue.

A chocolate cake with strawberry filling, strawberry frosting, almond frosting and vanilla frosting for my partner’s niece's birthday, visually inspired by her favorite One Piece character Tony Tony Chopper, a real first for a more chaotic and less literal cake baker like me.

An attempt at this sourdough bread with rye, but that is also still a work in progress as I would have loved its crumb to be just a little more holey.

Hibiscus tacos and incredibly juicy vegan tamales at Gordo’s Cantina in Ridgewood. Doughnuts and vegemite martinis at Dromedary Doughnuts and the associated speakeasy in Bushwick. Perfectly hearty and comforting, unfancy Mediterranean food at Oasis in Williamsburg with a dear friend.

I think I rarely walk away from your pieces fully grocking the physics concept you play with, but I do get a better understanding. An hour long read of even a good textbook probably wouldn't get me There, anyway. I completed whole college class semesters without fully understanding the semiconductor design I was allegedly there for, to my shame.

What I do get from your writing is good friction, and imagination. I reread those book quotes and your surrounding commentary several times, trying to get my brain to follow the same path and be hit with something special.

Whether I get There or not, that experience and effort encourages new understanding, and I relished imagining, even if naively, of the causality of physics in reverse. I appreciated pondering radical new possibilities of our actual universe.

I loved my notion of physics as firm, hard, applied mathematics being challenged (surely not for the first time).

I deeply value that these ideas can flourish in affirming spaces, and I lament that institutions haven't been.

It is genuinely probable that a revolutionary understanding of our natural world that feels feminine, and thus contrary to the vibes of centuries of white dude scientists, awaits discovery or mainstream acceptance.

And maybe it doesn't have to be a truth claim to be valuable. The metaphors we take from reality and its quirks also matter, as you show time and time again. Do we choose to harm imaginary cats or compare entangled particles to connected beings?

What I am left with this morning, unable to sleep so reading this at 5:30AM, is a sense of connectedness. To the hooting owl outside whose sound was familiar enough to normally be ignored or annoyed by. To the hamster in my home making little noises that I know by heart. To the wind, silent or causing creaks in my house's wood frame.

Thank you.

I bounce all over the place with these comments, so also thanks for your patience.