Thanks for reading my newsletter! All opinions expressed here are strictly my own.

If you are here because you like my writing about science or my Instagrams about cooking, you may not be interested in every essay in this space, but please do stick around until I loop back to whatever it is that we have in common. Find me on Twitter and I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

Note: I wrote the bulk of this letter before the shooting at Club Q in Colorado Springs and did not expect to be writing about connection at a time when a place where authentic connections, and safe, often life-saving ones, could be made would be so brutally assaulted. I do not have words for this, but recommend this devastatingly beautiful meditation on queer spaces by John Paul Brammer.

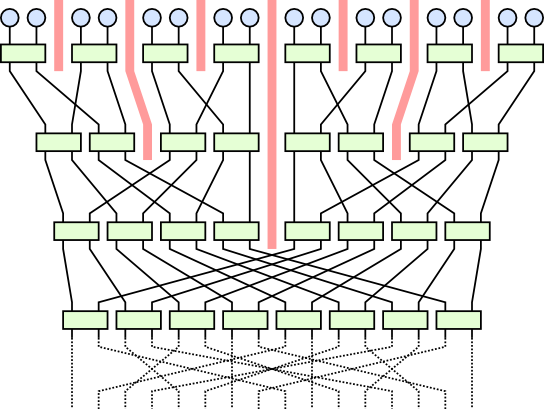

TENSOR NETWORK*

A diagram of tensor network, as they are used in quantum physics, by Andy Ferris

A few weeks ago, I was interviewing a seasoned scientist at a company with name recognition. It was an unseasonably warm day and the sunlight that made it through the many tall windows in my office was deceptively faint. I squinted a little, thinking about shrugging off my cardigan. It was close to lunch time, and somewhere in my torso a small irritation of a nascent hunger was taking form.

“I am also a condensed matter physicist by training so I hope we can speak the same language,” the scientists said.

I asked a very broad, generic question, the kind that, as I often say at the start of an interview, benefits the “very general reader”. The scientist answered broadly as well, alternating corporate speak and physics vernacular with a solid measure of genuine enthusiasm throughout.

The interview was about a new device that holds lots of promise for doing lots of things, but after some back-and-forth I realized we were deep in a detailed discussion of what were essentially very fancy wires. Later, the third person on the call, the relations, publicity and optics (not the physics kind) professional showed me the company’s promotional materials and photographs of these wires did actually look quite cool. I was amused by imagining the next one-on-one meeting with my immediate superior where I would let them know that we’ve really, urgently must publish something about fancy wires.

***

There are simultaneously too many and not enough wires in my home. In the kitchen, I have a charger for my watch and one for my phone permanently plugged in right by the glass vase we use to store ladles and large wooden spoons. In the bedroom, my partner’s bedside table is a tangle of chargers, converters, extenders and more wires. The perimeter of our living room is covered in thin copper wires held down with masking tape, crawling up our walls to keep the very bulky amplifier in one corner connected to the very bulky speakers in the two others. In the summer, when my mom visited, both she and my partner bought a fan and cables for it which made them confront the scarcity of both outlets and space in our apartment. Our floor was, for a few weeks, a tangle that reflected, albeit poorly, the tangling of live that was happening between the three of us.

***

The scientific journal Science recently published a special issue dedicated to brain connectivity. On the cover, set against a dark blue background, was an illustration of nerve fibers that sit between the two hemispheres of the brain. A C-shaped collection of thick and thin, curving and bending cylinders colored in red and yellow, it looked almost like bristles on an old toothbrush or an utterly deformed broom. It reminded me of those smaller colorful cables you can uncover by stripping the black outer coating off thicker ones.

“The human brain has ~86 billion neurons, each with up to 10,000 synapses. Neurons form hundreds of cortical areas and subcortical nuclei, which are connected by nerve fibers,” informed an article by Markus Axer and Katrin Amunts. Neurons are the nerve cells that serve as fundamental building blocks of our nervous systems and synapses are the way they are connected. The number of neurons cited here, all in your one single head, is about 11 times larger than the number of people currently on Earth.

Another article, by Peter Stern, put the issue of brain connectivity more poetically. It was titled “No neuron is an island” with Stern writing that

“The brain is so much more than its constituent cells. Each neuron in the brain connects with thousands of other neurons—but instead of a cacophony of connections, we have a synchronized symphony.”

Review and research papers in the journal made a coherent argument: many scientists now think that it is the wiring of the brain, the so-called connectome that all those fibers belong to, that makes a difference for cognition or disease.

“The imaging of connections in the living brain has provided an opportunity to identify the driving factors behind the neurobiology of cognition,” wrote Michel Thiebaut de Schotten and Stephanie J. Forkel. They went on to explain how studying connectivity differences between different species and between different humans helps elucidate steps in the evolution of the brain as well as different levels of cognitive ability. Cognitive functions deteriorate, or at least change, when there are short circuits and glitches and unexpected crossings in the brain’s wiring.

***

In my day job, I often engage with work that brings physics in close contact with computer science and engineering, and the intersection of the three is often a fertile ground for devices and systems that are described as neuromorphic. Neuro-morphic as in structured like the brain.

You may build your system out of silicon or you may build it out of extremely cold atoms, but you have to build something that can stand in for a neuron. Then, you have to connect these artificial neurons together. Only if they are connected can you begin to think about gaining and harnessing brain-like properties within this system.

A researcher aiming to do that by studying neuromorphic computers once told me that the brain is so attractive as a model because it is exceptionally good at doing a lot for what is, if we were talking about computers, not that much energy. Scientists who are not physicists balk at the idea that the brain is just like a computer, but the comparison is tempting. (A psychologist recently asked me, with some bewilderment, whether physicists like to call things brain-like because we all have brains so it’s the most familiar place of mystery and wonder for us to go to.)

Brains use electrical connections to process information and they do so in a way that requires wiring small parts of it (neurons) together. Computers are, at their most basic, made by wiring small circuits into bigger circuits then pushing electric signals through them. If you consider a simple enough computer function, a scientist that is oldschool enough may be able to convert it to a circuit diagram. Researchers that are working on developing quantum computers are also drawing so-called quantum circuits which also encode how different parts within the computer connect to each other. As noted in that special issue of Science, techniques like certain types of MRI scans allow researchers to map out the brain’s “wiring diagram” extremely precisely as well.

***

In physics, systems whose behavior is marked by electrons moving around and grouping together, or maybe keeping each other stuck in place by exerting repulsive forces on all their neighbors, often feature emergent properties. Emergence is a shorthand for something being bigger, richer, more complex than a sum of its parts.

If you jam a lot of electrons together in the correct arrangement of atoms, under correct conditions, you can see them display behaviors that they really should not unless there is something more happening than there just being many of them. A key example is superconductivity. Here, materials that do not conduct electricity well can start to conduct electricity perfectly, without losing any energy or heating up as currents pass through them. This only happens under special conditions, but when it does happen, physicists believe that it is a consequence of behaviors electrons can take on only as a collective.

Electrical currents and electrical signals in your phone, computer, and wires behind your fridge are related to how electrons move around. In the brain, charged particles that move between its parts are different from electrons, but the idea of something novel and rich emerging from all that coordinated electric action remains compelling. In fact, Thiebaut de Schotten and Forkel write that

“What we know, who we are, and how we communicate with others are ascribed through integrative brain mechanisms. Therefore, to understand the origin of our identity, we need to decipher how connections between brain regions orchestrate our brain functions at the individual level.”

In other words, who we are to ourselves and to others, as defined by our thoughts and actions, it all emerges from how the brain is wired. It’s a bolder claim than saying a chunk of ceramic can suddenly conduct very well, yet one that evidence seems ot be pointing towards more and more.

***

The wires strewn all around my home are, also, mostly there to enable me to define myself to myself and others. While I cannot directly wire myself to another person or find a way to transmit an electrical signal into their mind, many of the wires keep my phone and my computer going, the devices that allow me to project and connect myself to others electronically.

I hate describing myself as being very online, but I can be easily found and perceived on multiple social media platforms, none of which paint an ambiguous image of what kind of connection I am seeking. While Twitter is quickly devolving into uselessness, it is the place where I am a person full of wonder for science who gets to exercise that wonder professionally. On Instagram, you can see that I eat the same smoothie every morning, dress according to a slacks-button-down-cardigan formula for work, and cook dinner on all days except Friday. (It’s a dishonest platform meant for highlight reels and performative vulnerability, but I am not immune to its mores.) On LinkedIn I am all business. On Facebook, I am just making sure my parents still know I am around, doing well and being productive.

Social media and its algorithms flatten you into being just one thing when you are really a lot more than a few templates can hold, but I have still been making a lot more friends on the Internet than in physical spaces for years. As long as my phone stays connected, I too can stay connected. Connected to people who may be highly curated and responding to who I am within a niche, but the chance of a deeper connection some day is still always there.

***

A meme about mushrooms sharing memes recently made me chuckle because so many of my friendships are maintained by the daily sharing of funny or, at times, tender Instagram posts of screenshots of some other very-online content, a trick that briefly works even when we are all feeling as muddy and low as some mushrooms look. Certainly, this form of communication will never replace an in-person dinner or a long walk, and relationships do stagnate without those more tangible experiences, but it helps to keep a pathway for our electrical signals open.

Mushrooms do not have a nervous system at all, but they do stay connected to each other through electrical signals, so much so that some scientists have interpreted their mushroom experiments to mean that mushrooms are sharing language. A Guardian article on the topic immediately makes the comparison with the brain:

“fungi conduct electrical impulses through long, underground filamentous structures called hyphae – similar to how nerve cells transmit information in humans.”

Another, on the Conversation, paints them as a protective social network for trees, whose roots they connect with, instead:

“Experiments using plants connected only by mycorrhizal fungi have shown that when one plant within the network is attacked by insects, the defense responses of neighboring plants activate too. It seems that warning signals are transmitted via the fungal network.”

The phrase “woodwide web” gets bandied about, and I want to be annoyed by the need to compare everything to the Internet just like my friend was annoyed by the ubiquity of the brain as a reference point. But there is also something inspirational about the mushroom network.

Mushrooms can seemingly grow out of nothing more than a little dirt, and in that dirt they can find nourishment from dead and discarded debris of past forest lives. Activist and writer adrienne maree brown calls them a “great detoxer” and says we should learn from their ability to find nourishment even when things are breaking. Food writer Alicia Kennedy contrasts them with “tech-foods”, the kinds that need monocrops and labs before they can show up on your plate, as a food that is naturally as sustainable as it gets because of how humbly but powerfully it grows.

There is very little about the worldwide web that connects people that is optimized for finding nourishment even in a world that seems to be steadily breaking. Our networks are also meant to constantly grow so that corporations that make them can constantly grow profits. There is nothing sustainable about that. Except that in moments when we wrestle away the algorithm’s grip on our feeds and stop daydreaming about growing our personal brands, we can cultivate small moments of emotional sustenance. For me, this is why I have a hard time letting go of social media, even when I know it is often truly harmful.

This past summer I made an oyster mushroom dish for my mom based on a recipe my Instagram friend Lin wrote drawing on food from her own home and parents. I’ve never met Lin in person because we have always lived on different continents, but putting that meal together, without an expectation of getting a shout-out from an influencer, just feeling grateful for a friend’s work, then watching my mom discover the mushrooms’ flavors made me feel like the three of us were able to share something. Like the electric impulses in our hearts and minds maybe briefly synchronized across distance.

***

As a physics reporter, I have always written a lot about quantum computers, but recently quantum Internet has been showing up on my to-do list rather regularly as well. Both are in an early stage of breaking into public consciousness so my editors and I tend to debate whether I need to define what they are in each article. Saying that a quantum computer is a computer that is quantum is not informative; the word quantum just hides too much complexity. For the quantum Internet, however, saying that it may end up being like the Internet we have now, but using quantum technology, is a little more accurate.

The book on the quantum Internet is that it will be more safe than the “regular” Internet. This is because quantum cryptography is much harder to break than any cryptographic protocols that banks or online retailers use now. Ultimately, however, it will still be a technology that keeps us connected.

The creators of the Internet were probably unable to imagine everything it would come to be used for. Similarly, there are already ideas about how the quantum version could be used for things bigger than communication, like research that could uncover details of physical reality, the fundamental constants that dictate the way space, time and forces are structured, with new clarity. But physicists, computer scientists and engineers that are building the quantum Internet right now have a fairly solid template for how a communication network comes about and how it evolves. In fact, a sizable portion of them seem to be my age and remember the Internet showing up in its slow, screechy modem form when they were teens or pre-teens. I imagine at least some remember it as a new tool for finding and talking to other weird or nerdy kids.

In talking to researchers about the quantum Internet I have consistently been wowed by how much has been done already. A researcher recently told me that many cities are already “more quantum” than I might think because different labs are successfully sharing quantum signals. A team in China even used similar technology to link up with a satellite. Responding to my faux-naive “will we make this happen in the next 5 years” researchers have consistently assured me that it will take significantly less long. One startup founder even promised I’d get to visit their company’s devices once they’re installed within New York, bringing a quantum network to my backyard, sometime very soon.

It’s odd to daydream about the quantum Internet while Twitter, a huge chunk of what seems to constitute the loud parts of the Internet that we have now, is being reduced to a crumbling mess. In addition to bringing into question issues of public safety (how will agencies communicate with broad swaths of people in real time during emergencies?) and actual revolutions, the quick decline of this network is having repercussions on careers and businesses, especially among journalists who have found both editors and scoops on its pages.

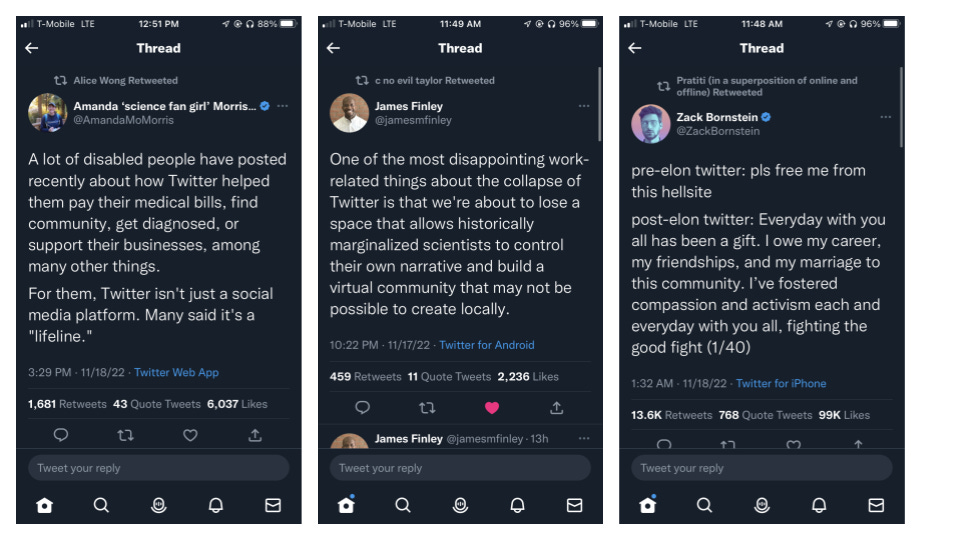

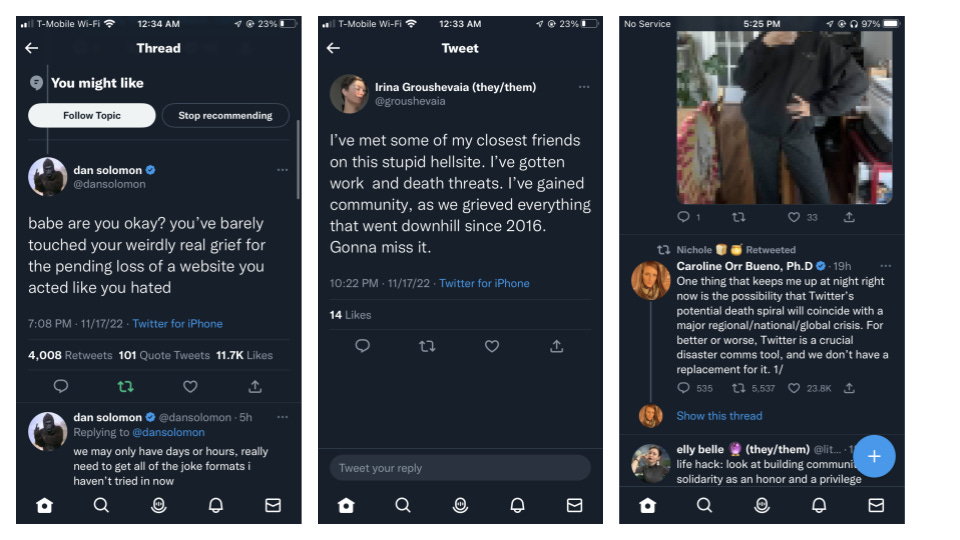

Yet, many Tweets that are still being served up to me when I succumb to the temptation of the infinite scroll are also lamenting an expected loss of community. Platforms like Twitter changed how we think of who gets to be a culture critic or a public intellectual or even just someone who we go to for laughs, and they once provided a way to connect people with similar interests or who were navigating similar concerns.

For me, I saw and still do see a much more nuanced and caring discussion of academia, mental health among young scholars and issues surrounding graduate labor on Twitter than I ever heard when I was physically rubbing shoulders with academics on the daily and trying to become one of them. I have also learned of many queer writers and scholars on Twitter, and their Tweets both inspired and educated me. I am almost never surprised when I hear friends recount meeting other friends on Twitter. It’s easy to be cynical and dramatic, but the fact remains that no matter how toxic many social media networks are, they are still a quick and easy way to connect with someone, and many of us need that.

In a capitalist world where our control over our time, and at times our bodies, is constantly challenged, and our personhood and health reduced to culture wars and issues of mind numbing bureaucracy, do we really have enough energy and resources to resist the promise of thousands of potential, if not friends then at least friendly acquaintances, just a few posts and clicks away? Not every friendship that starts as being “mutuals” on social media manages to become a genuine connection, in part because genuine connections also require time and energy, but the feeling of its potentiality can be mildly intoxicating.

“We may not like the fact that we are wired such that our well-being depends on our connections with others, but the facts are the facts,” psychologist Matthew Lieberman told Scientific American a few years ago. His research straddles psychology and neuroscience and he combines the methods from both disciplines to hypothesize that there is objective evidence within our brains for how miserable we are bound to get when we are not networked into friend groups and connected with others.

Social media is addicting because of its persuasive design and all the algorithmic tricks companies like Twitter and Meta play to keep us scrolling, but we all know and hate that by now. And we are all nostalgic for times before the algorithm, for chronological timelines and less polished posts and fewer aspirational influencers. Most of us are not really looking to abolish social media, we just want to remove the parts that trick our brains into discomfort and exhaustion and keep the parts that, as Lieberman implies, are hardwired into us.

“I always think building genuine connections with people will be easy and casual, but then I am mortified when it never is,” a friend I had made on the Internet texted me a few weeks ago. I understood - building channels for rich, complex, sometimes mysterious communication that is really necessary for closeness is so much harder than making better wires for odd, futuristic machines.

Best,

Karmela

*In mathematics, tensors are objects that take many inputs and act on many independent variables at once. A tensor network then refers to a collection of tensors that are connected i.e. if you feed numbers or information into one, some of what comes out will then be fed into another. Typically, tensor networks are used to conduct and graphically keep track of multi-dimensional calculations, for instance for systems containing many particles where each may be considered as adding a degree of freedom or a slot in the tensor.

Do you like Ultracold? Help me grow this newsletter by recommending it to a friend or sharing this letter on social media.

ABOUT ME LATELY

WRITING

I attended IBM’s Quantum Summit and wrote about two of the company’s announcements from the event - the completion of the biggest quantum computer yet and the fact that IBM researchers have run the biggest quantum program yet on one of their machines. It was really interesting to spend the day immersed in both quantum science and the business of quantum as an emerging technology and I loved running into colleagues and acquaintances from my past research life and getting to hear their takes on it all.

I also loved reporting this story about researchers using a microscopic sample of extremely cold atoms to emulate a curved, expanding universe. In our universe, the speed of light and the way light curves around planets reflects the fundamental structure of spacetime, all of its flats and nooks and crannies. In this experiment, the team worked out how to make sound play the role of light, and because they could manipulate sound by pushing the atoms around with lasers, they could build a “tiny universe” that had exactly the structure they wanted. They set out to see whether in such a universe, and our own universe is not dissimilar to it, pairs of particles and antiparticles get produced out of nothingness, a phenomenon that cannot be directly observed in actual space. Remarkably, the experiment was successful, opening the door for more universes and more phenomena that are typically out of the reach of space-based studies to be tested in the lab.

LEARNING

How to approach researchers at awkward receptions without being more awkward than the event’s baseline. How to speak to people that were my superiors in the past without treating them as such now when they are only really older than me. How to pick small fights with editors without letting them occlude big ideas we agree on. How to make it through five rounds of edits on a 400-word story and not completely lose all confidence. How to spend time with corporate leaders without feeling like a child and talk to them with a realistic sense of expertise.

How to see a famous owl in Central Park even though I know nothing about birds. How to relax at a party where everyone is cooler than me, and everyone’s mouth is full of food in every conversation. How to visit a friend whose cats look like literal demons. How to deal with a roll cake that won’t roll. How to skip a workout without spiraling too deeply into body negativity. How to recognize when I am picking a fight only because I am tired and anxious and how to go to bed and have a great day tomorrow instead.

What an air resonance is for a violin and what combination tones are, because I forgot everything I learned in music school a few decades ago.

READING

This essay by poet Carl Phillips for the Yale Review on finding community as a writer where he powerfully notes:

“The larger importance of a writing community, at best, is as an ongoing reminder of likeness: not that we makers of meaning are interchangeable, in any way the same, but that we share something… Likeness, then, as a system of exchanged support, community—again, at best—as a space of generosity, which can take many forms, including just being there, like taking another’s hand in one’s own for a time, and holding it, no words required.”

This brief letter by Stacie-Marie Ishamel where she writes

“Let go of the conviction of intent. Do the reading. Cite the authors who enabled your comprehension. Ask who gets left out of the footnotes of history. Consider who you’re writing out of the story”

and then

“It’s hard to ask different questions if your perspective hasn’t changed.”

This issue of Blackbird Spyplane about how “be yourself” is terrible fashion advice. It really resonated with me to read that

“It’s a point worth reiterating: The power to change the way you appear — and, with it, the power to shed, inhabit and experiment with different identities — is one of the most fundamentally liberatory things about wearing clothes, period.”

And I was equally struck by the essay ending with the very Blackbird-Spyplane-like assertion that

“Because the true GOAT-tier writer, much like the true GOAT-tier clothes-rocker, keeps shapeshifting — albeit in more sophisticated and self-assured ways, and with a firmer bedrock of self-knowledge — long after they’ve become goated.

The only alternative is to BE(come a dusty, fossilized version of) YOURSELF.”

This Vox story about astronauts and social media that features the surreal sentence:

“Still, the line between astronaut and influencer is only set to grow more complex as we enter this next space age.”

LISTENING

Beauty and the Beat by the Go-Go’s and Substance by New Order because I am in some sort of a new wave phase and these two bands sit on opposite sides of the broad spectrum of this genre. The former is bright, poppy, almost cheesy in that California way that is easy to quickly acknowledge and then immediately forget while the latter is more stripped down yet somehow more emotional.

On a similar note, this post-punk playlist that Sasha Frere-Jones put together to accompany his style guide on Shfl has kept my attention for more than late afternoons at work.

WATCHING

I’m still really enamored with and wowed by Andor which continues to deliver everything that’s ever been good about Star Wars and then some. I was blown away by the direction and acting in episode ten which featured both a prison break and a really impassioned speech by a character we actually still know very little about, but even the quieter parts of the show have, so far, managed to pack quite a few punches. I partly sunk so much time into the animated Clone Wars series, presumably a kids’ show, because I am a sucker for worldbuilding and a filling in of gaps, whether they be in galactic empire politics or Jedi lore. Andor takes that project a step further and forgoes Force magic in favor of the real nitty-gritty, messy, human details of how both dictatorships and rebellions are made. This is quickly becoming a show where it is easy to both root for and severely judge almost every character, where many are sympathetic, but no-one is unambiguously likable. I am inclined to believe that this is the closest to real politics that this particular fictional universe has ever gotten.

We spread the second season of Reservation Dogs over a few weeks and not binging the show really gave me the chance to appreciate how good and devoid of filler episodes it is. Certainly the shorter than usual format as far as so-called prestige TV goes, helps pack in substance. But the writers also did not take that as an excuse to become more gimmicky than in season one nor to suddenly take an unexpected turn towards overly self-aware or dramatic. The obvious reference point for this show is Atlanta, but Atlanta eventually got bloated and heavy with a self-awareness that was too much and too meta. Reservation Dogs, on the other hand, is still very earnest, and very earnestly funny. It deals with both issues very particular to the Native experience and very general to what it’s like to grow up with more tenderness than irreverence, and this makes it feel more meaningful. The auntie episode is fantastic, the psychedelics episode is fantastic, the influencer episode is fantastic, the group home episode is fantastic and they are all, as is the finale, both devastating and revelatory at once.

As is often the case, on the movie front my partner and I have been reaching for classics. We recently spent a night with Paul Verhoeven’s 1987 Robocop and another with the 1973 The Exorcist directed by William Friedkin. I had never watched either in full and was surprised by how much I liked them both. The plot of the Exorcist barely makes sense, but the atmosphere and character work alternate between being immaculate and comical, often striking just the right balance. Robocop, in contrast, is a very deliberately executed satire that would make a great double feature with something like Videodrome - you can misguidedly enjoy its violence, but the commentary is so pointed and so cleverly self-aware that it eventually inevitably catches up to you. Really, it had me in the bag from the moment it opened with a Frank Miller Batman-esque news segment and only got better from there.

EATING

Tomato bisque with sticky tempeh and roasted broccoli and then about a thousand more soups at a very joyous soup-themed potluck at a dear friend’s home.

A pumpkin cake with chocolate ganache topping and sprinkles, the recipe for which is in one of the master documents of vegan meals, projects and tricks I had put together a few years ago.

A full Thanksgiving dinner a few days before Thanksgiving because I wanted to share a big meal with a friend who will not be around on the actual day. This was my first time eating stuffing and I was lowkey blown away. And the mushroom gravy from the Mississippi Vegan cookbook still stands undefeated.