The Standard Model

On trying to write poetry as a recovering physicist

Thanks for reading my newsletter! All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on X, Instagram and Bluesky. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

THE STANDARD MODEL

Would it have been worth while,

To have bitten off the matter with a smile,

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it towards some overwhelming question,

T. S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

I. DETACHED

April is national poetry month and on April 1st I decide to participate in a challenge where you receive a prompt for writing a poem every day, but I have to squabble with my best friend first.

I tell them that I feel like I’m not loose enough to really write poetry. I’m not saying this part out loud, but I am playing an archetype here and invoking my training as a scientist without saying the words. My best friend says that they don’t like it when I talk about myself like that. They are right to not like it, but it is always easier to flatten yourself than open up to something new. Saying “I was trained as a physicist so all I know is how to analyse from a distance, and that is not poetry,” is an easy way to build a wall around myself, a wall that I hope will keep out the embarrassment of trying and failing, or even just trying hard enough to meet some part of myself I’ve managed to avoid so far. (In a poem in Joshua Jennifer Espinoza’s I Don’t Want to Be Understood, the speaker says: “Poems are where I used to hide parts of myself I was afraid of, so they couldn't touch me.”)

My best friend says that I talk about myself not being “xyz enough” more often than is kind to myself and instead of absorbing the concern, I write back something snappy and sharp enough to sting through the blue-white glow of the smartphone screen. This is now an argument and it is not at all about poetry. I’m at work and a tension sets into my neck as I arrange Word documents across my three screens. When my phone buzzes with messages, the words are textureless and grating in their artificial flatness. This is not the right medium for a serious conversation about friendship, resentment and self-worth. “I think we’re missing each other here which is why I think we need to talk live,” reads the next text and amidst the ever-present sense of urgency that comes with working in a newsroom a touch of gratitude asserts itself and pushes down on my shoulders. My heart opens a little. We make plans for the weekend.

On my lunch break, I try to write the first poem of the challenge. The prompt is a “self-portait poem” so I scribble some statements starting with “I” in my little notebook. I don’t write by hand very often, but when I do it is in a scrawl that is tiny and almost always proves illegible when revisited. My hand is already pre-emptively obscuring whatever it is about the “I” that it was meant to be recording. It’s sort of always been like that, my own hands making my own words a problem once they hit paper. As a middle schooler I wrote everything in all caps. My notebooks were filled with block letters as if I wanted to yell at any teacher that chose to grade me. By college, I turned to the other extreme and my letters started to shrink and crowd each other, like tracks made by some erratic, lost and inky creature that keeps retracing its steps. I felt validated by how many of my math and physics professors operated at a similar level of illegibility. Writing things down, in a notebook or a blackboard, was for the sake of a ritual, sometimes also a performance, more than utility. When you zeroed in on a discovery, maybe even a truth, you turned it into a crisp equation that could hold its own in a peer reviewed paper and kept the notebooks and the scribbles strictly for yourself.

“My writing practice is too detached to really jive with poetry,” I said at the beginning of that squabble. Staring at the ruled notebook page against the unpleasant mix of yellow indoor lights and gray counters in the office cafeteria, as I was writing my self-portrait, I tussled with the word “detached.” I had meant to say that my writing practice allows me to have distance from myself, to withdraw the connection between me who is feeling and me who is writing, the me who observes the universe and the me who contains it, as if it was a tenuous bridge that only sometimes has a purpose. Now, however, my physical writing practice, the scribbling and the inkiness, was starting to feel detached from clarity and meaning, and overly attached, overly connected, to some vulnerable part of me that had to scuttle across the page in a way that could not be leveraged to peer into me more closely later.

This, of course, was ridiculous - I just finished writing a memoir. Something about centering the “I” in a poem, rather than an essay, made the act of writing feel tremendously risky. But essay comes from the French word for “attempt” or “trial,” it is related to “assay,” it sounds almost like performing a scientific experiment, just with words. A physicist like me would be comfortable there, they would love the essay’s Latin forefather “exigere” - to test or to measure.

A few days later, my best friend drove us upstate and we spent a few hours walking by a river. It was rainy and a drizzle kept following us, making light refract before it got to us wherever we looked. Surrounded by the soft and shiny magic of the moment, we talked things out and promised to read our poems to each other at the month’s end.

I didn't write a poem that day.

II. RESIGNED

On the second day of April I actually try to write a poem, but I just end up arguing with the prompt.

Today, the list wants me to write about anger, fear and grief but I am too sad and tired to follow its prescribed steps

Write a letter, it says

Circle your fears, it implores

Look for connections, it nudges

There is an equation: Anger = Grief + Fear

I am an equation kind of girlie, an equation kind of boi, but right now I can’t compute anger

Am I grieving? There’s a step in the list where I am meant to enumerate all my losses, create the dataset at the bottom of my grief, my grief emergent

Do you know that Le Guin story where a sorrowful narrator is caught in an indeterminate state like Schrodinger’s cat?

I just learned about it yesterday

I think I’ve known about it my whole life

II. LOCKED

In 1907, philosopher and logician Bertrand Russell wrote an essay titled “The Study of Mathematics,” in which he implored his colleagues to remember the ideals of their profession instead of focusing on its utility. Not pulling any punches, he designated the pursuit of the latter to “dry pedants” who misunderstand the purpose of their knowledge so strongly that “though they spend their lives on the steps leading up to those sacred doors, they turn their backs upon the temple so resolutely that its very existence is forgotten.” Russell did not discount how important mathematics is for making machines work, getting from one place to another in the most efficient manner and the many other practicalities of life that can be optimized or better understood after being recast as equations that can be manipulated on paper or, nowadays, on a computer. But his essay elevates something else: beauty.

He writes:

“Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show. The true spirit of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than man, which is the touchstone of the highest excellence, is to be found in mathematics as surely as in poetry. What is best in mathematics deserves not merely to be learnt as a task, but to be assimilated as a part of daily thought, and brought again and again before the mind with ever-renewed encouragement.”

Later, Russell describes the practice of mathematics as an entryway into a world of pure thought, one where our “nobler impulses can escape from the dreary exile of the actual world.” The sense of being more than man can lead us here, and so, he seems to imply, can poetry. A notable difference between physics and mathematics is exactly that while some mathematicians feel comfortable doing their work in abstract realms far from the actual world, the actual world is always hanging over physicists’ heads.

Physicists and mathematicians certainly mix within academia, but there are disagreements on the exact position of the fundamental boundaries between their work. Russell was a logicist, which means that he believed that all mathematics can be reduced to logic and exorcised of all signs of human intuition - stern perfection that transcends man. Maybe poets could get there too, but certainly not physicists. Weighed down by the muck of the actual world, the one where every experiment has statistical errors, all numbers have to be rounded past a certain decimal place and many equations remain unsolvable, what sort of beauty could their tools possibly unlock? What sort of poetry?

The situation in physics has for the past hundred years been further complicated by quantum mechanics, the most successful physical theory we have ever managed to write down and test in experiments, yet one that no-one really knows how to translate into clear mental images or truly accurate words. When the mathematics of quantum theory leaves the abstract realm and makes contact with the tangible world, who is experimenting with quantum objects, even who is watching them, really seems to matter. There is no such thing as transcendence or detachment.

Physicists like Nobel laureate Anton Zeilinger go as far as to say that the theory has nothing to do with objective reality, just everyone’s very subjective gathering of information about however reality presents to them. Others, like Carlo Rovelli, posit that no object really exists and that the only thing that is true and real is the relationships between them. Over a thousand physicists were recently surveyed on their views on how to best interpret quantum mechanics and found to both disagree with each other and trust their own views only very weakly. Ironically, one of quantum’s forefathers, Niels Bohr, compared physicists' work to exactly that of poets in an attempt to underscore his belief that interpretational questions simply cannot be answered definitively and exactly. “When it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry. The poet, too, is not nearly so concerned with describing facts as with creating images and establishing mental connections,” he is reported to have said in 1920.

“Truth beyond facts,” I made a note to myself. I wrote a poem about Walther Gerlach discovering the quantum mechanical property of spin by shooting silver atoms at special screen. It’s last line: “Caution. Lust. For knowledge. To be certain.”

III. WEIGHTED

In 2011, New Scientist published a series of poems by prominent Victorian scientists with a snappy preamble which asserted that “When formulae failed them, James Clerk Maxwell and other eminent men of science turned to verse, with often hilarious results.” In 2022, Physics Today ran an essay about physics and poetry that grappled to find connections between the two in such a dismissive way that I wondered why the piece had been commissioned in the first place. “To research this essay, I trawled the Poetry Foundation’s online collection of poems for instances in which physical phenomena are put to poetic use. I found barely a handful,” wrote its author, an impossible statement given that the world as we know it is largely composed of physical phenomena. I tried to trawl too, turning to both the Internet and my bookshelves.

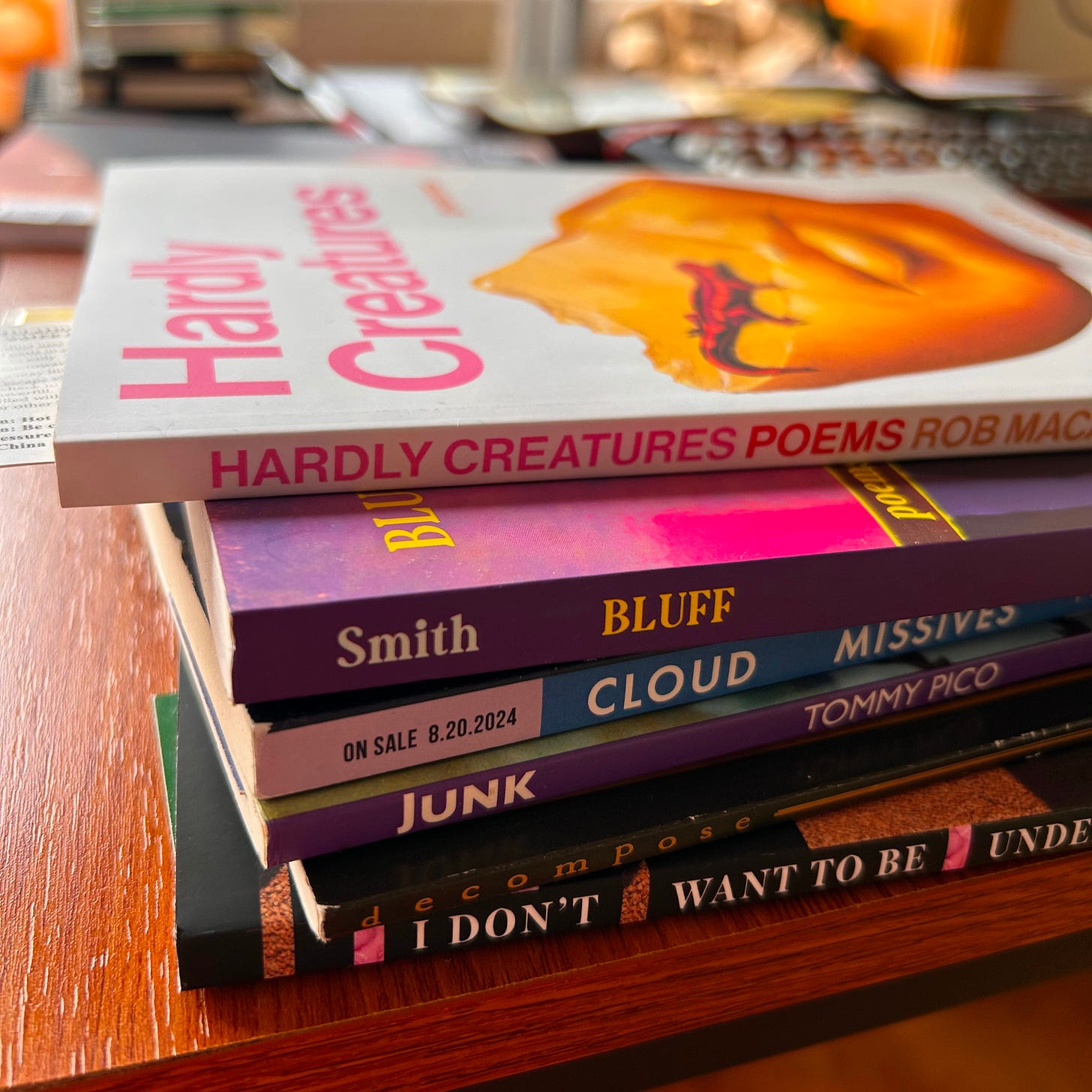

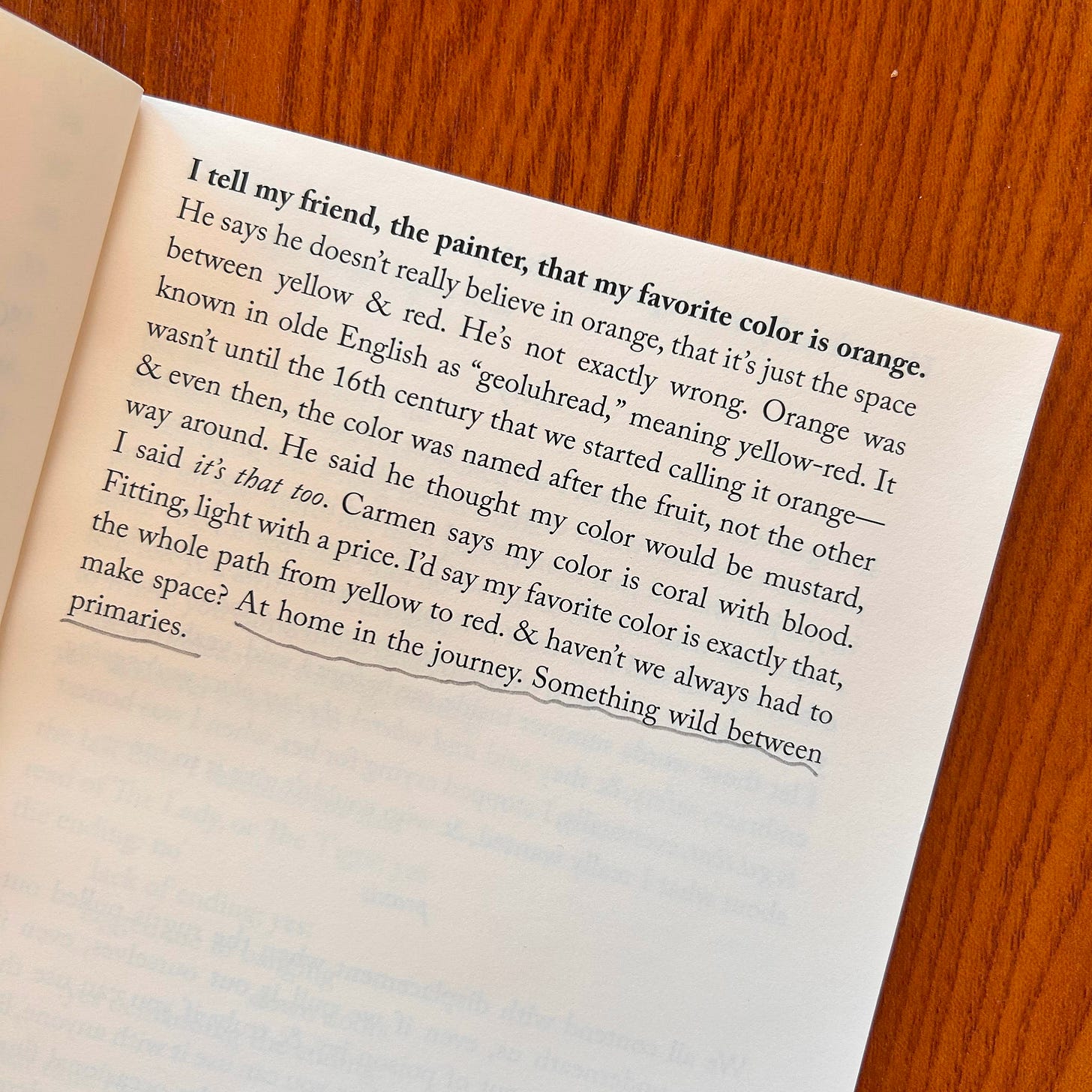

I found Rebecca Elson writing “Sometimes as an antidote\ To fear of death, \ I eat the stars.” and Tracy K. Smith chronicling the world as it was when the Hubble Telescope showed us stars more clearly than ever before. I found June Jordan capturing the essence of Bell’s inequality with heartbreaking accuracy. I remembered that my friend Seamus Fey wrote about the color orange as the range of wavelengths and frequencies between mustard and scarlet, just without ever saying “wavelength” or “frequency.” When I opened my copy of Tommy Pico’s Junk, I found that I had underlined “As Junk I’m less an element n more the entire periodic table,” back in 2018 and wedged a physicist’s business card between the pages so I’d not lose the spot.

I felt for Russell. The point of physical phenomena in poetry did not seem to be one of usefulness. All their tricky connection to physicists’ experiences and intuitions aside, they were cyphers for a world of truth more than they were tools.

I didn’t set out to write poems about physics back in April, but those that I can still read certainly betray some of its vocabulary. This is not surprising: the language of physics is the language in which I built my career as a writer. Had I not become a writer, it would have been the language with which I’d have composed my story of the reality. Grappling with whether my practice of using those words, whether scribbling them illegibly or typing them on a screen, was too detached from my own feelings and spots so soft that they feel dangerously vulnerable or not detached from them enough, made me realize how inevitable their weight is in either case. In-between the mucky actual world of physics and the pure mathematical world of transcendent truths, a world of words that can’t decide exactly which they want to belong to started to take shape.

I tried another poem that could be mistaken for a self-portrait. The prompt encouraged me to “Be wild, be slippery, be brash in ways that are both you and not-you” and start every line with “I am.” I wrote:

I am the cosmic force

I am the white hot power

I am the bright light that tears the world apart at the microscopic level

I am the kernel of energy at the core of existence

I am inflation

I am expansion

I am the only constant in your cosmos

I am the cloud of probabilities, all of them breathtaking

I am the collapse

I am the grand theory

I am the big unification

I burn in reality’s bowels

I scoffed at it. Then I loved it. “Oh wow,” my best friend said when I read it to them. I was a little embarrassed. Inside of me something loosened a little, maybe a word became a little more heavy with truth.

***

I tried to read Ralph Waldo Emerson’s discussion of the “true poet” from the 1840s, but when he wrote:

[T]here is a great public power, on which [the poet] can draw, by unlocking, at all risks, his human doors, and suffering the ethereal tides to roll and circulate through him: then he is caught up into the life of the Universe, his speech is thunder, his thought is law, and his words are universally intelligible as the plants and animals. … if in any manner we can stimulate this instinct, new passages are opened for us into nature, the mind flows into and through things hardest and highest

I was stunned by how much, to me, he sounded like a physicist.

III. CREATED

I love to listen to poets write about writing poetry because I love learning about process. It is the equivalent of the Methods section in any good paper, the one where the nitty gritty of why we think we know what we know is made most obvious.

“Probably the most unsexy thing about Hardly Creatures is that I wrote the whole thing using a big spreadsheet, which was really helpful for my Virgo Moon. Or maybe my Virgo Moon made me do it. Each spreadsheet, I would essentially draft a poem in a column where the top cell would be like the big main idea I was trying to get at. Then each cell below would have a line I thought might fit, a general idea for the form, a concept I wanted to make sure was included in some way. I just collected these columns for months,” says poet Rob Macaisa Colgate on a podcast and though he finds the method to be “both wildly uncool and the opposite of poetic,” it strikes me as ingenious. I don’t have a Virgo Moon, but I did spend my whole life studying physics and so many objects that physicists love are spreadsheet’s philosophical cousins.

Consider, for instance, the Standard Model of particle physics. You can think about it as a cookbook for the universe or a catalogue of all of its ingredients accompanied by in-depth information on how they mix. It puts together all the particle types that we know exist as well as all the forces that we know them to exert on each other. Pick an assortment of particles and the Standard Model will tell you whether there is a force that can make them stick to each other, whether they can combine to make another particle, or whether they are absolutely incompatible. A proton, for instance, hides three other particles, and the Standard Model will tell you about them, as if the proton was a pea pod you can unshell to reveal smaller and more concentrated bits of the same stuff inside it.

The “model” part of the Standard Model is of the mathematical sort, which is to say that it is abstract and needs to be translated into symbols that are not fully detached from meaning when presented to us. There are equations that capture the Standard Model, but most often you see it represented as a table, as rows and columns oddly reminiscent of a spreadsheet. You put all the particles that carry forces into a column called “bosons” and the particles that comprise stuff get sorted in a column called “fermions.” The columns have been named for long enough that even the empty cells within them carry meaning. For instance, we have not yet detected a particle that would carry the force of gravity, but physicists that believe that it exists are saving a spot for it in the boson column. They hope to eventually have enough experimental evidence of this particle’s existence to place it within this table, just like happened every time we have seen a particle in an accelerator or some detector caught particles that travelled to us from outer space. You can’t really see a fermion or a boson, at least not with the naked eye, but they seem to be integral for the way we feel our world, the way to manifests to us at the scale of human experience and nothing more transcendent. The Standard Model is like a cosmic spreadsheet that just makes it easier to keep track of it all.

In Physics magazine, poet Amy Catanzano recounted how visiting the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland was, for her, just another way of practicing “poiēsis,” an activity that brings something into being, a process more akin to creation than discovery. “When physicists construct the conditions for discoveries, such as the Higgs boson at CERN in Switzerland, and when poets construct interventions into culture and consciousness, both are practicing poiēsis, the artistic activity of making,” she wrote about it. But what exactly is being made in a particle accelerator?

Certainly, there must be a sharp line between discovery and creation. Within a particle accelerator, chunks of stuff that we are very familiar with like charged atoms of lead or gold are smashed together at such incredible speeds and energies that they break apart and produce showers of other particles in the process. You could argue that those particles were there the whole time, hidden within the atoms and the collision forced them out, like applying pressure to a pea pod makes the pea jump out. You could also say that by combining the ingredients of atoms and energy, physicists create the particle for - or from - their grand spreadsheet. Where you fall, and even whether you think there is an ambiguity here, depends on your philosophical stance towards empirical science.

A few weeks ago, I reported a story about another famous spreadsheet - the periodic table of elements - and how physicists are using another set of giant machines to create elements that were at one point pencilled in at the table’s lowest row and their place there was confirmed not by finding them in nature but rather creating them in the lab. There is something of a race currently going on between several research teams, in California, Japan, China and Russia, to add the next element - element 120 - to the periodic table. It currently goes by the unceremonious moniker of “unbinilium,” but once it has actually been created it will be named something more descriptive, like “ununoctium” becoming “oganesson” in 2016, honoring the nuclear physicist Yuri Oganessian. I have a favorite in the element 120 race, I told my partner, but he was stuck on whether an element that only exists for half a millisecond in a highly specialized lab gets to be called real. It feels like the physicists are cheating, he said. You can’t just bump into these elements out there in the real world.

Yet, much like particles in accelerators, once the conditions are exactly right, when the right physical mechanisms are triggered under optimal circumstances, these elements do become a part of the real world. They fit into the spreadsheets, they fit the general themes and uphold relationships, even if they did have to be nudged into existence. This nudging is where the physicists’ expertise really shines. As Catanzano suggests, this is where they are doing poetry. Poetry is an intervention in making words that seem universal suddenly become extremely specific, pointed and personal and it is a way to take a word that feels so narrow as to be a wound and blow it up into pieces that undergird everyone’s world, that don’t belong to anyone in particular. Physics shares this dual property, it makes the abstract tangible, pulling the bits of a word that seems to transcend us down into the greasy, sputtering world of experiments and machines, and it gives us permission to take small observations and dream up their most grand generalizations. In Cantanzano’s words “Poetry is an advanced technology like a particle collider or a telescope, extending the senses, intellect, and imagination.”

***

When I learned physics it came to me neatly packaged as a rigorous field of study with practical, respectable aims. I knew many physicists were actually dreamers; I had read the popular science books and romanticized it all as much as I could. But a hundred years after Russell’s essay, in a field less pure than mathematics, I was being nudged into being more of a pedant than a poet. This was expected and so it could also easily become comfortable. Trying to write poetry, even as a purely self-imposed challenge, because I wanted to share a creative practice with a friend and stretch myself as a writer, on the other hand, never allowed me to become that complacent. I got mired in the very human work of ordering, assembling, nudging, and hoping for something like creation. When April ended, I dropped the practice, but kept thinking about it.

In meetings, I would open my little notebook to jot down a deadline or the name of a scientist that I really ought to call and a poem would stare at me from the opposite page. “Don’t forget that you are not just a gatherer of facts,” it seemed to say. “Don’t forget that what you sometimes do is an intervention. Even a spreadsheet can foster poiēsis, so why couldn’t your words?” I’d feel a little called out, a little mocked even. Surreptitiously, like shame-eating ice cream with the freezer door still open, I’d feed myself one last bite of self-pity, a bittersweet assertion that I was right to think I wouldn’t ever make a great poet. Then, the thing that had come loose within me would rattle again and I knew that what I really need to do is stop talking to myself like that.

Best,

Karmela

Piper Alexis Harron has written interestingly in ways that connect with your thinking and feeling.