Extra: You Can’t Network Your Way Out of Oppression

On being a gender minority in a professional setting

Thanks for reading my newsletter! This is an extra edition reflecting on my recent experience of being a “gender minority” in a professional setting, a somewhat rough first person piece rather than a deeply researched essay. The next regularly scheduled edition of Ultracold will be a Media/Diet roundup on February 10th.

All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on X, Instagram and Bluesky.

Extra: You Can’t Network Your Way Out of Oppression

“Next year this conference might as well not exist,” I say to a friend over tahdig rice and stewed eggplant.

We’re catching up. They tell me about their transmasc support group and the happy trail they grew from testosterone shots. I open a box of cookies I used to eat as a child in Croatia and talk about having written a book’s worth of words recently. Inevitably, we talk about moms and ill-fated crushes. The conference, a yearly gathering for “women and gender minorities” in physics sponsored by a national professional organization, is among the least interesting things I think to bring up, it’s just the next substantial block of color in my calendar. Our long and relaxed dinner color-coded in purple touches the three day long block of orange for work related travel.

This is happening before the president blames Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) for a tragic accident in Washington, DC and before many scientists see their funds frozen while someone is presumably trying to find out whether they were aligned with the new administration’s rightwing agenda1. It is also happening after an executive order that has rendered all transgender people in the US, for now, effectively nonexistent. For two people fully invalid according to the ideology of those in power, my friend and I are having a great time. We barely speak of the executive order. But the next day, on my long train ride to the conference, which unambiguously falls under the DEI umbrella, I can’t help thinking about it.

What scares me the most is the new administration’s language: the use of phrases like “biological truth” in the executive order invites the government to adjudicate how observations from science should be interpreted. The word “biological” is meant to convey scientific objectivity and wash the whole thing of its ideological stink. But it's paradoxical here: if something is so true as to be a “biological fact,” it should not have to be enforced by an executive action.

Of course, science has been put into service of ideology many times before, and governments have never not at least dabbled in declaring what a scientifically provable fact is, but the directness of this latest attempt feels exceptionally sinister. I start to worry about the undergraduate women and gender minorities that I am about to spend the weekend with. Do they stand a chance to mature into scientists whose truths will not be imposed by politicians and bureaucrats? And then there's the other part of it. In a reality that is quickly being reshaped by a slew of rash and radical actions from above, what is the meaning of being a “gender minority”?

I don’t mean that in an existential or an emotional sense; I know those things intimately. I mean it in a professional capacity, if there even is such a thing as being a professional and a person who may not legally exist at once.

I’ve been attending conferences like this one for long enough that I remember when “and gender minorities” was not spelled out on flyers and invitations. And I remember when those words became more mainstream. One memory that stands out is of a trans man in one of my past physics departments objecting to being invited to the ‘lunch for women in physics’ and the name of the event getting changed. Behind the scenes, there were conversations about the best words the group should use to signal inclusion. In retrospect, they were missing the point - the man’s concern wasn’t with the name, it was with the assumption that the group that would speak to his experience of physics was women.

Later, I would meet many more queer people who find phrases like “women and gender minorities” or “women and femmes” to be too vague to make anyone feel all that safe or seen. These days, I feel exactly the same. Language that is imprecise, like “gender minorities,” always makes me worry that organizers are looking to disengage from true efforts at inclusion as they are signaling that anyone who is not cisgender belongs to one homogenous group. In women’s spaces specifically, I worry that it is a code word for transmisogyny, that trans women would otherwise not be included.

Phrases like “women and gender minorities” are meant to facilitate solidarity but the idea fails almost by default. A cisgender woman and a transgender man, for example, will likely only rarely experience the same kind of discrimination or live under the same material conditions. This is not to say that they should not be in solidarity, but it does mean that putting them in the same space may require lots of education and patience before that solidarity can become meaningful. Practically, this makes participating in some spaces more onerous than beneficial for some people; including them fails to produce empowerment.

The practical impact of how one identifies (who they are) is something that is always top of mind for me as a trans person who has not changed my body through medical intervention2. My experience is materially so different from that of my trans kin who need access to medication or to afford surgery and be able to take time off from work to recover from it. These are also the people who will be most affected by this latest slew of political attacks on trans people, again it will be the concrete conditions of how they live their lives that will become harder. Spaces that are created for broad and vague groups of people are often ill-equipped to address this sort of distinction, or even purposely shy away from it, though the differences in how each of us is affected will be impossible to not bring with us into those spaces.

Still, for all my worry and skepticism, I have never declined an invitation to a professional event where I would be folded into the amorphous mass of “gender minority.” The situation always strikes me as lose-lose: if I decline the invitation because the space may not be truly inclusive, that will only make it more homogenous and less likely to ever become more inclusive. If someone whose experience is similar to mine does show up, they will only be more lonely. And those people are the ones I really want to offer not just solidarity but a material intervention in the shape of my presence and whatever help, professional or otherwise, is available to me.

“It’s really ok for women to have their own spaces, it’s ok to not invite people like me,” I say to my partner as I’m packing. “But if I’m invited I guess I should go. Me from a few years ago would have loved to see me from now speak.”

***

At the conference, it quickly becomes clear to me that I am not here to engage with my gender identity or my identity as a scientist but that it will all, instead, be about being a professional.

I miss the opening speeches because I am working late at my job and the train ride is very long, but in the morning the first plenary talk is by a physicist who became a speechwriter for a dean at a powerful Ivy League institution. She says this makes the storyteller within her feel valid. The keynote speaker is a physicist who became an analyst, consultant and an entrepreneur. She seems to specialize in advising on AI, but I quite frankly do not understand most of the words in her bio. Across the talks, the young people in the room are encouraged to recognize all parts of themselves as important then turn that into something they can parlay into a career, in physics or otherwise. Most parts of me, right now, are scared of the government.

When an undergraduate asks one of the speakers whether she regrets anything about her career path, she tells an anecdote about not networking enough with the C-suite at her first job. Naively, I expect her to say something like ‘I wish I’d gotten a dog,’ so I am surprised at the narrow career focus of her answer. When another young person asks how she would deal with gender discrimination in the workplace, the speaker refers them to official channels for reporting such incidents that all companies must have. “Sometimes it’s not that straightforward to tell that they’re being discriminatory,” she acknowledges but no actual advice follows.

At dinner, I am feeling rattled by the sheer amount of business jargon I have witnessed, and ask the students that I am sharing the meal with if they understood what the speakers of the day actually did in their day-to-day. Heads shake over poorly seasoned Brussels sprouts and a jarringly pink salad dressing. We bond over our confusion a little, then someone asks me about what quantum field theory (QFT) classes are like and I feel just a little less out of place. “I hate bra-ket notation, but I love integrals,” a student says. “You will love-love QFT then,” I say and briefly find hope in how wide she smiles.

***

Other than one panel featuring queer physicists and a few questions across other panels, which were not mandatory and many of them happened in parallel3, I witness very little discussion about gender or the politics of it. There is a lot of networking and our gender is almost incidental to it. There is some talk about the material conditions of labor of young scientists, but those words don’t really get spoken out loud - these conversations are all about moving up, seeking success through efficient connections and well-timed follow-ups, creating opportunities for yourself and by yourself.

As a panelist, before I set off for the conference, I am instructed to not talk about getting lucky in my career. Instead, the organizers would like me to emphasize how I created the conditions for my luck, how I courted luck until it was ready to relent and swoon into my arms. I understand that it can be demoralizing for young people to think that they have to be lucky to get ahead. I have also personally experienced the disappointment of thinking that working really hard was all it took to succeed then getting personally unlucky and not succeeding at all. This instruction then doesn’t sit well with me; it feels too simple and too rose-tinted. But various speakers keep referencing it, mostly to reaffirm how they did in fact have a hand in their own good fortune.

Can you create your own luck if you’re being harassed for who you are? Can you create your own luck if you don’t have generational wealth? If you’re an immigrant on a precarious visa? If your parents are undocumented? If the government says your gender doesn’t exist? None of the talks that were mandatory for every conference attendee engage with these issues.

“Maybe luck had something to do with it, but I busted my ass every day,” says the last speaker of the conference, a physicist who went to work for the Air Force. I learn that the Air Force has a lot of great internships for physicists interested in ultracold atoms, which I wrote my graduate thesis about. Throughout the talk I can’t focus on ultracold atoms, which I love, because every mention of an aircraft makes me think about Gaza.

***

After each of my panels, students come up to ask me about getting a start in science writing, and to ask if they could add me on LinkedIn. Sheepishly, I give them all my business cards. I am trying very hard to be an adult and a professional.

When a student shares that she sometimes feels like she should stay in academia because leaving would prove that women just are not cut out for physics research, I find myself telling her that it’s not her responsibility to represent every woman physicist, that she should not feel that pressure and make big life decisions based on it. “Would a cishet man feel like that?” I say with an edge in my voice. The other panelists enthusiastically agree.

It’s not that this is a fully wrong sentiment, but it is a reactive one, and it centers individual decision making in the face of a system that always wins against the individual. I am ashamed of speaking so rashly and giving such narrow advice. In response to a similar question the next day, I try to talk more about organizing and finding strength and possibility of change within a collective, about connecting with other women in real, material ways instead of taking on the burden of representing them all, but there is less enthusiasm for that.

This is another lose-lose offered to us by the sociopolitical system that we live within. Minoritized individuals are made to feel like they are responsible for everyone in their group and that is part of the burden of being minoritized. But missing the opportunity to take that instinct and turn it into collective action and instead double down on individuality keeps the system going and sustains its ability to minoritize people.

The irony is not lost on me: I’ve partly come to this conference because I didn’t want someone else to feel alone and like there is no future on display for them.

***

On the last day of the conference a student thanks me for ”being the only nonbinary adult here,” and I am briefly rendered speechless. Then, we bond over being unsure whether including us “gender minorities” in the weekend was an afterthought. I tell them to reach out to me about anything anytime. It’s all I can offer, really. (It’s probably not enough.)

At work the next day my manager tells me that their manager expressed concern for how I may be affected by the current political situation. Again, I’m not sure what to say. I offer thanks and a reassurance that I’ll be fine. I keep working even after everyone leaves the office. I understand that this is the exact wrong way to cope.

***

In line for lunch at the conference I chat with a friendly particle physicist. We both dislike some of the New York Times’ coverage of particle physics and she inadvertently gives me some great language for writing about hadrons when I ask about her research. I learn that she’s not speaking about particles at this conference but she did just moderate the panel on queer physicists. She’s not a member of the queer community but she has a trans child and she’s worried. I’m worried too. Allies are incredibly important right now, I try to say, but we’re both awkward about having this conversation, unsure of just how upset a person is allowed to be in this professional setting where everyone is seemingly happily networking.

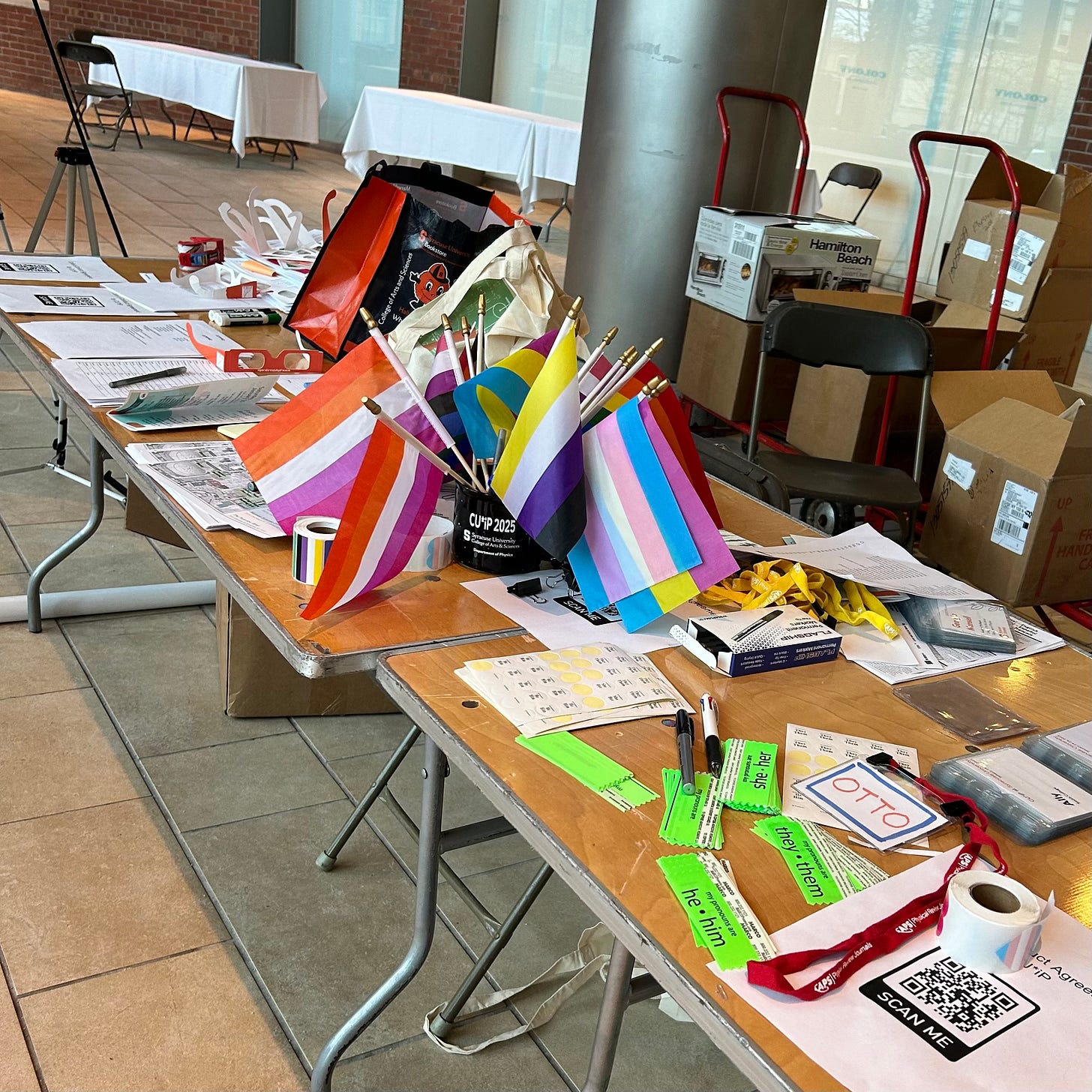

Lunch is served right next to the check-in table which is littered with a variety of rainbow flags, some so specific that a lifetime of being terminally online does not help me decode them. There are pronoun tags that conference attendees can affix to their badges but this is not mandatory so many of them didn’t. The optics of inclusion are halfway there, but that is not enough for them to translate into anything close to comfort for me or the particle physicist. By the time we each grab a dubious chickpea wrap and head to separate lunch tables, neither of us has said the word “trans” out loud.

***

I spent my time on the train ride to the conference and back reading Metastasis: The Rise of the Cancer-Industrial Complex and the Horizons of Care by Nafis Hasan. This book, upcoming from Common Notions Press in February is a somewhat dense but very necessary exploration of how the political ideology within which science happens influences that science. Hasan focuses on cancer research, which is both his background and affects many, but one of the book’s chapters takes on an analysis of the labor of modern-day scientists more broadly. Having attended graduate school at a large research university, I have some firsthand experience of this, especially because I was active in the graduate employees labor union. I am less naïve here than when it comes to the world of corporations. Still, seeing all the arguments laid out in one place was rather serendipitously well timed and helped me understand just why the weekend left me feeling deflated.

Hasan writes:

“[Graduate students and postdocs] who are “fortunate” enough to enter academia suffer exploitative labor conditions. The lack of academic jobs and prevalence of exploitative conditions have not stopped the universities from churning out more and more PhDs. The year 2022 saw the highest number of doctorates awarded across US universities in a single academic year. Now that migration to the private sector is the norm, the PhD is seen as a marketable skill that can be utilized in every sector.”

This was the part of being a professional scientist that I had experienced as a graduate student. I was overworked and underpaid and faced a scarce and hostile job market. At the conference, one of the speakers shared that only 1 out of 6 physics PhDs goes on to become a tenure-track professor. Choosing to highlight this unfairly centers tenure-track positions as the only respectable academic outcome, but the statistic is concerning even if you can’t get past that. It suggests that pursuing science for the sake of curiosity, which academia still somewhat makes room for, is less and less of a realistic goal, and it is becoming a true practical necessity to teach curious physics students how to recast their personal drive for knowing as something more marketable and utilitarian.

I worry that only presenting young women and gender minority physicists with examples of professionals who more or less left physics signals that they are not allowed to dream of studying physics just because they want to know things, but that worry really speaks to my own inability to accept the realities of doing science under late stage capitalism. Partly then this weekend upset me because I found very little evidence of others mourning that loss of, for the lack of a better word, romance with the cosmos. An acquaintance who I used to organize with voiced frustration about the state of the job market when we spoke privately, and that was about it. Everything that was presented to the young people at the conference just encouraged them to learn how to play by the rules of the game instead of questioning why it has to be the way it is.

The fact that the game is typically rigged exactly against women and gender minorities did not come up because it would endanger the idea that the game simply has to be played. I’ve heard it said that identity precedes politics, but here really it was the belief in a false meritocracy of the market that was strong enough to overshadow identity completely. What does it mean to be a gender minority in a professional setting in 2025 then? It doesn’t seem to mean much at all, maybe just that you have to try a little harder in your already aspirational program of trying extremely hard.

It would seem that scientists, people famously good at thinking about complex systems, may have the tools to know better, but Hasan offers a valuable historical insight:

“In the decades following the McCarthy era, anticommunism continued to influence social views of science. Therefore, scientific research in the US was carefully and deliberately sterilized of politics through the lens of rationality and neutrality. The void left behind has been filled by a liberal politics, which promotes the individualistic view of society and misunderstands the levers of power. Politics has turned into “voting harder” for candidates who “champion science” (e.g., the leading magazine Nature endorsed Joe Biden) or advocating for policy-based changes through congregations like the March for Science—acts that rely on scientists as individual members of society”

Not surprisingly, he ends this section by underlining that the only path towards true change lies in collective organizing and mass movements. I underlined the words and tried to imagine a different kind of conference, one less rooted in individualism and neoliberal values and more in-tune with the revolutionary potential within womanhood and queerness.

I thought of sessions centering labor organizing, about events with elders who had fought hostile governmental regulations before, about trainings on how to protect fellow scientist and science students in the face of immigration raids, sessions with lawyers who may offer information on what an employer, like a university, legally can and cannot do, how-to’s for setting up local networks of mutual aid, for preserving data that may disappear from federally run websites, for supporting colleagues impacted by lack of healthcare - and a few sessions on science that is genuinely inspiring whether it leads to attainment of marketable skills or not. At night, maybe there would be stargazing or, if it is especially chilly out, workshops on writing speculative fiction as a way to imagine the futures we want to live.

Maybe that sounds overly idealistic, but I have attended gatherings that had this type of programming in the past4 so I know it can’t be done. Those gatherings, however, were always organized by students, many of them queer and people of color, and without the oversight of some large, national body. They may have been less polished and there may have been fewer flags and pins and offers of internships, but they always left me feeling inspired and hopeful. But even if I didn’t have those experiences to use as my reference, I think I’d always choose idealism over the notion that what can save a young minoritized person right now is getting a great job in some nameless corporation or the military.

Best,

Karmela

Addendum: As I was putting finishing touches on this essay, reports came in that CDC scientists have been asked to retract any papers that they may have submitted to journals and that contain terms like “gender, transgender, pregnant person, pregnant people, LGBT, transsexual, non-binary, nonbinary, assigned male at birth, assigned female at birth, biologically male, biologically female.” In my mind, this makes it all the more necessary that we move away from inclusion as a way to bring people into the system and towards learning how to dismantle it before it fully erases us from history and all of its means of knowledge production.

This may have changed by the time this essay is published as it seems that several judges have tried to intervene.

For the past year or so I have been sitting with the notion that I may want to experience some aspects of a medical transition, but after the election that curiosity has, quite frankly, been replaced with fear.

I was disappointed to find that I was speaking on a panel that happened at the same time as the one focusing on queer physicists.

Here is a vintage edition of Ultracold where I discuss facilitating a workshop on owning your privilege in academic spaces at an Access Network assembly in 2019:

Constructive Proof

Hi and thanks for subscribing to my newsletter! The breakdown is as follows: a personal essay on top of the letter and some more concrete life updates, current media favorites and a recipe at its bottom (pancakes!) so feel free to skip to whatever interests you. (Please feel free to hit the Reply button at any time, for any purpose.)

Oh wow I was at cu*ip this year too! Loved hearing your perspective, beautifully written <3

So many illuminating statements of truth here. Thank you.