All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on X, Instagram and TikTok. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

MEDIA/DIET JANUARY 2025

Thanks for reading my newsletter! This is a monthly edition of Ultracold where I share informal thoughts on media and food that I have consumed recently. A slightly more polished essay will run on the 27th, roughly centered on the idea of how winter vacations, and how we imagine them, are changing as the climate does.

MEDIA

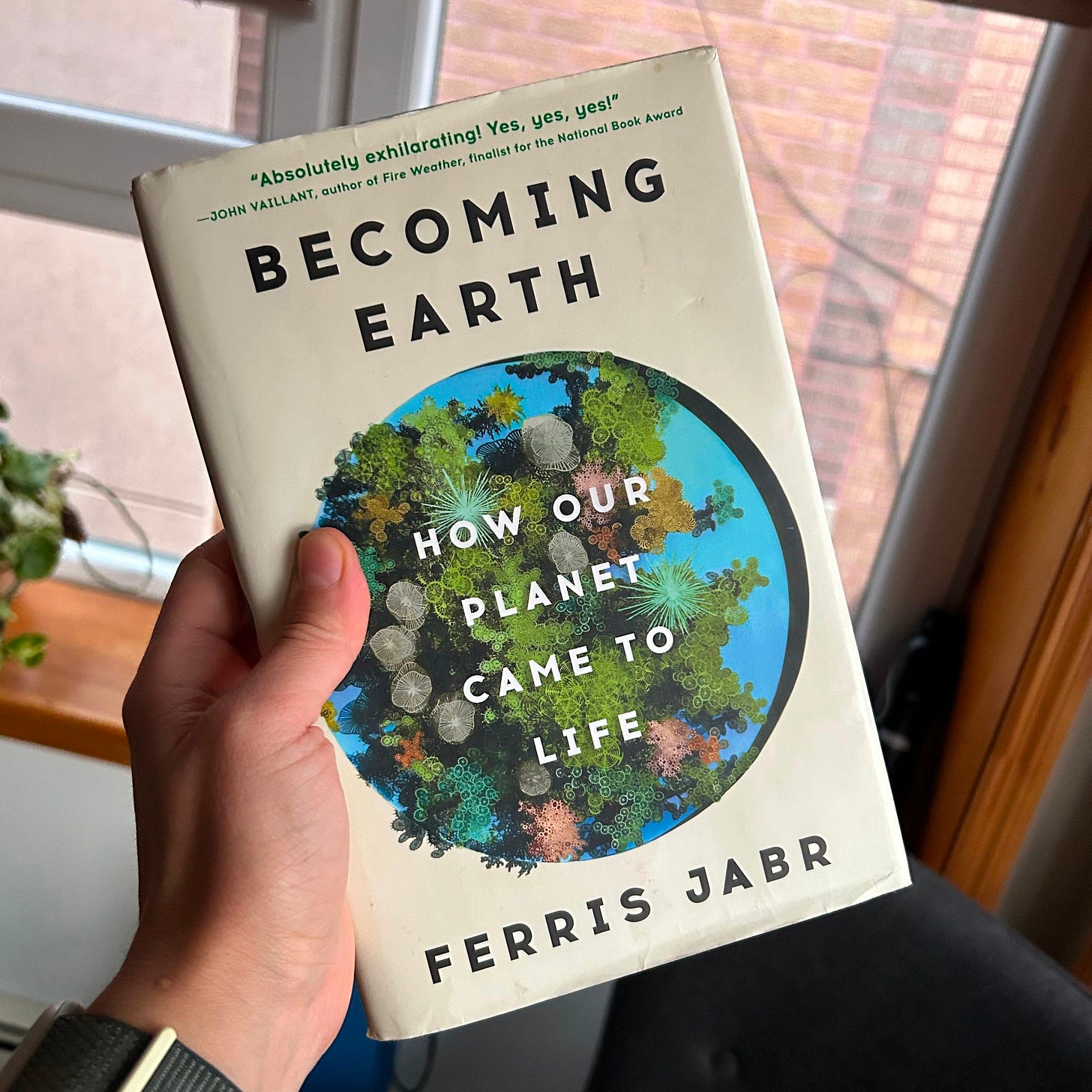

I often worry that my reading habits will be my downfall as a writer. Specifically, I worry that I don’t read enough science writing and journalism in order to be a good science writer myself, even though this is the work that pays my bills. But I am also weary of narrowing my focus so much that it becomes a sort of tunnel vision, and believe that best writers find inspiration across genres. When I read popular science books then, I gravitate towards topics that are outside of my niche, a sort of middle ground between reading to learn more about science writing as craft and reading out of pure curiosity. I learned next to nothing about geology in school, I found biology classes dull, and my understanding of geophysics is very shallow so Ferris Jabr’s Becoming Earth: How Our Planet Came to Life, seemed like a great fit.

The book centers on the assertion that the Gaia hypothesis, the idea that the Earth itself is alive because we and other living creatures “are Earth - an outgrowth of its physical structure and an engine of its global cycles,” which was first proposed in the 1960s, ought to have a renaissance. Many scientists are quoted throughout the book, but this assertion is also Jabr’s own and he spent years gathering information that would help stand it up, traveling, interviewing, observing and otherwise going above and beyond simply reading research papers. This is commendable work and his thoroughness shows throughout the text.

I appreciated the conviction with which Jabr argues in favor of a revived Gaia hypothesis, often expressing it in his own voice, without hiding behind the presumed authority of a quote from a research paper or an interview. This is one of the selling points of the book - it is not what BDM recently criticised as “timid writing,” including the sections where Jabr writes about the climate crisis and his view on how we should meet it. But the structure and the style of the book, which I would argue are always correlated, made it difficult for me to fully appreciate the strength of his arguments.

Jabr is a magazine writer and though Becoming Earth is divided into three sections, each of which is subdivided into chapters, I could not shake the feeling that it would work better as a collection of essays, essentially magazine pieces, and less of an effort to weave them all into one narrative. Most chapters open with the story of one scientist or one phenomenon which is then elaborated on and put in context through very detail-rich, lush and lyrical writing. As the book progresses, Jabr is strengthening his argument through an abundance of scenes, anecdotes and facts. This allows him to take detours into both ornate nature writing and more dry recaps of geological history and planetary science, but it also forces him to spend many words on repeatedly reminding the reader what exactly his argument is.

While reading, I would get really caught up in a description of some exciting and gorgeous landscape or happening (corralling musk oxen in frozen Russian lands, climbing an incredibly tall tower above the Amazon, diving through kelp forests, looking for microbes deep, deep under the surface of the Earth… the journeys that Jabr takes to accompany scientists featured in the book really are exciting), just to then be shaken out if it by Jabr’s voice reminding me that I should be thinking about the Gaia hypothesis. The more I read the more I found the references back to the Earth being alive repetitive, the same kind of paragraph recapping the book’s central argument over and over again, even after dozens of pages had already convinced me of it. At some point I started to feel like the book’s narrator just did not trust me to connect the pieces of the story on my own. But I am not sure that this could have really been avoided without restructuring the book or sacrificing some of Jabr’s stylistic flourishes.

Almost certainly this is a biased assessment: my taste is shaped by my work and I work in news where brevity and clarity are often two sides of the same coin, and tight word counts rarely make room for flowery prose. In other words, as a science writer I am used to letting go of beautiful sentences when I can identify1 that they serve my thinking, or my aesthetic preferences, more than they serve the reader. Books are a different medium, and can allow for a lot more liberty and enjoyment of language, but even with that in mind I kept noticing sections where Becoming Earth could have been a more impactful read had it been edited just a little more tightly, and with a little more faith in the reader’s interest and understanding.

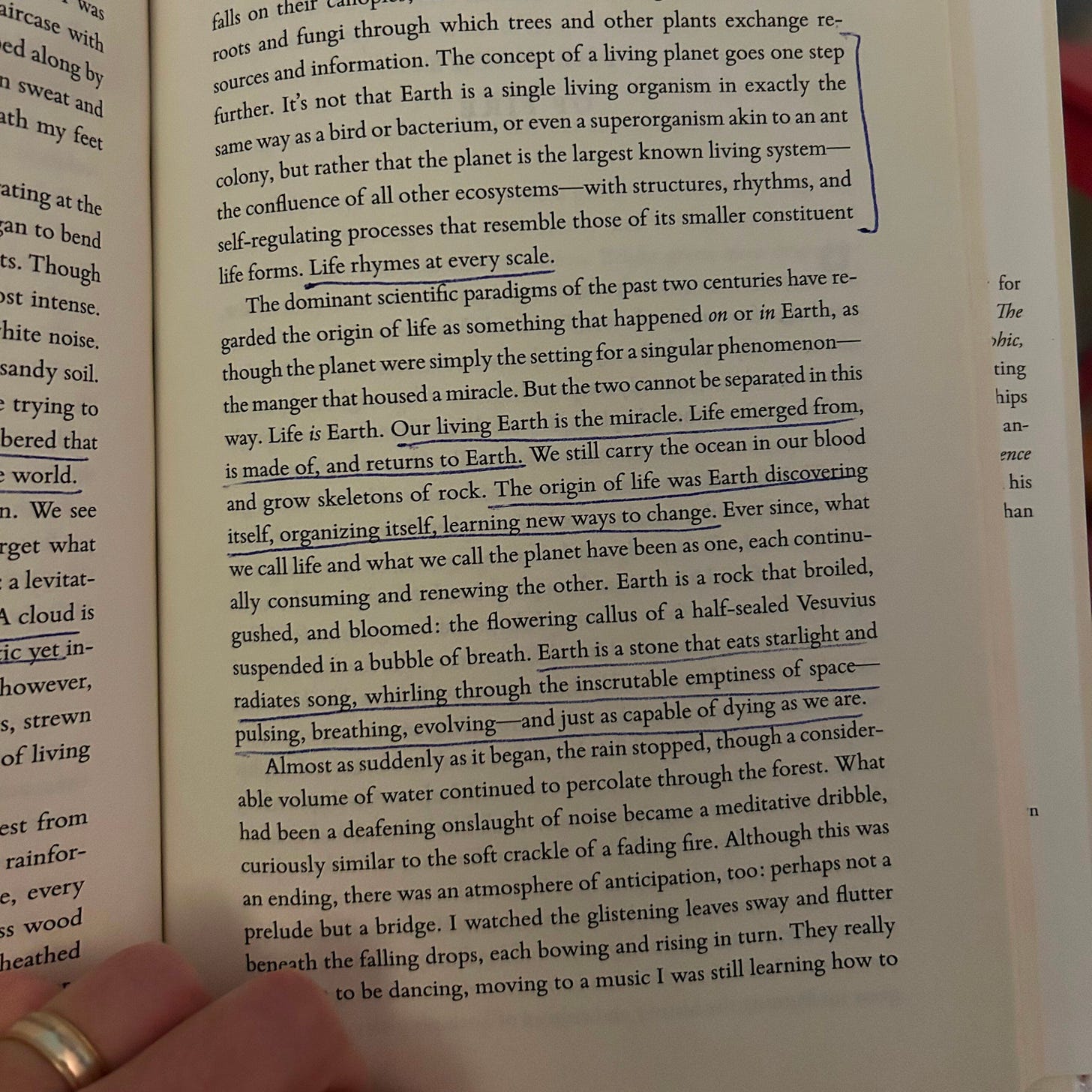

One repeating motif that stuck out to me in this way was how often Jabr’s introductions of scientists included describing their physical features, their clothes and often a science-related anecdote from their childhood. A conservationist is “tall and lean with glacier blue eyes, a boyish mop of brown hair, and a small scar on the right side of his chin,” an oceanographer is “dressed in jeans and a diamond-patterned sweater” while a colleague of theirs is “wearing maroon corduroys and a gray cardigan, her blonde hair pulled back into a neat braid,” another is a “dark-haired woman who animates her speech with quick, fluttering gestures,” and so on. Everyone wanted to be a scientist ever since they were a child, or they at least grew up adjacent to science.

I understand the function of these details - they are meant to quickly humanize the scientist and give the reader something to hold onto while a more abstract or technical idea heads their way - but I also very rarely find that they are employed successfully. This is a mannerism that well precedes Jabr and tends to be standard in magazine writing about science.2 It is something that science writers often learn to do by reading others. I was once a scientist and cannot help projecting my insecurities3 on how Jabr describes people that could have been my peers in another life, but I also worry that science writers detour into these flourishes because, again, they don’t have faith in their readers. That they worry that the reader will grow bored and overwhelmed by the kale salad of science if they’re not intermittently offered a cupcake in the form of a beautiful tree or a quirky researcher. I have had my share of arguments with editors because I believe that most readers can, and want to, handle more challenging and more abstract writing than institutions like magazines and publishers offer them. Reading Becoming Earth made me wonder how many such arguments had been had during its production.

Consequently, finishing the book left me with both awe for our planet and convoluted, and somewhat uncomfortable, thoughts about science writing. Was I too harsh with Jabr and maybe his style is what can get people excited about science for the first time? I could have simply been the wrong reader - too critical, too in-the-know, too much of a believer that science matters already. It is difficult to disentangle whether this style of science writing comes from writers and their own convictions, from editors and publishers who harbor doubts about selling and profiting from science books4, or whether this really just is the kind of science book that the average reader can complete and love.

Jabr is clearly awestruck by nature and has both tremendous knowledge and love for every species that he encounters and every breath, wink and shudder that the Earth executes under the watch of him and his companions. Should he not write about this earnestly and beautifully so that readers who do not love the Earth as deeply yet can get enticed to do so? The answer is probably some tantalizing “yes and,” in favor of keeping the feelings but streamlining the style, a line that is always very difficult to both find and walk.

And though I wanted to love this book more than I did, the idea that the Earth is not just a static, dead stage upon which life can thrive but that life is in fact an integral component of the Earth and keeps making and re-making it at all times, is absolutely stunning and touching. The notion that firm boundaries between “planet” and “life on the planet” simply do not exist, and that we can only have a future if we never stop thinking about that, is something that will stay with me. In this sense, I am grateful to Becoming Earth for giving me a new sense of kinship with our planet. But I think I would have been as grateful had this powerful message, which likely didn’t need that much sparkly varnish to begin with, been delivered more leanly and with less hand-holding.

What are your favorite popular science books? Let me know in the comments.

DIET

A few years into graduate school, I decided that the best way to stave off a nascent mental health crisis was to “clean up” my diet and double-down on fitness. What happened next was both very predictable and very complicated, which is to say very representative of being on the health side of the Internet in the 2010s, of being in graduate school without generational wealth in the 2000s, of living in a feminized body at almost any time in this century. But before the calorie-counting, the short lists of safe foods, and negative effects on both my mind and body, there were some bright spots. Most notably, I started eating breakfast.

Instead of occasionally grabbing a croissant and a cappuccino from my favorite campus coffee shop on the way to doze off in a course on mathematical methods for physics students or stumble through teaching laboratory exercises to equally sleepy undergraduates, I now had a breakfast regimen. Two times a week I ate a roasted sweet potato with a handful of chickpeas and some tahini, and for the rest of the week I had a green smoothie. Almost ten years have passed and an awful lot changed, but the breakfast smoothie stuck.

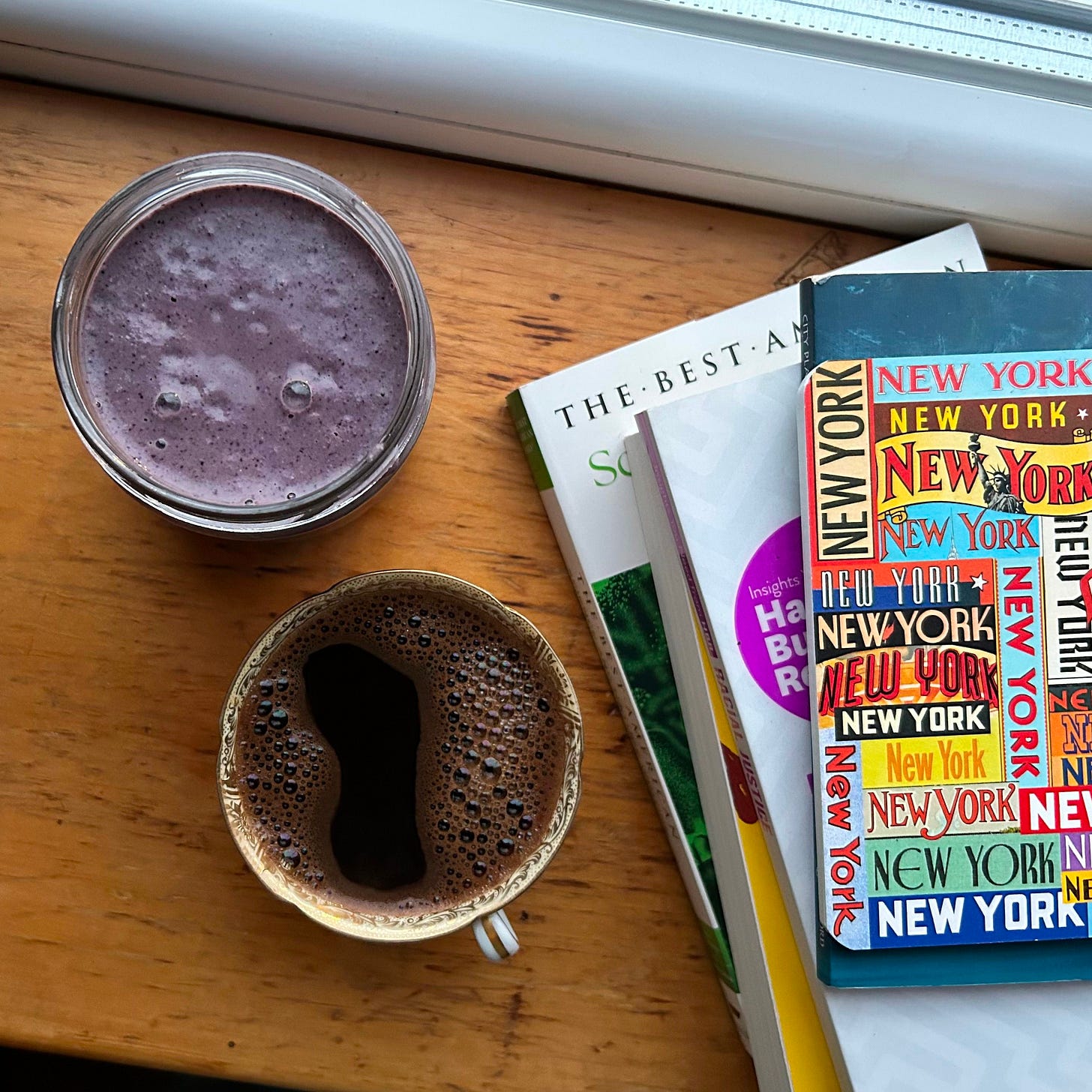

I have excuses for this: it’s quick to make, it’s easy to eat even when I don’t feel like it, you can cram all sorts of food groups into it, it tastes nice if you have a sweet tooth - and I very much do. I think this is all true but there is also a factor of habit, of something adjacent to ritual, and also of what I imagine reclamation feels like. No, I am not dieting anymore, but I don’t have to be so scared of falling into old habits that I could not have a smoothie for breakfast. And it is a breakfast that my partner and I can make for each other and share without taking a lot of time or dirtying many dishes, which makes it an easy-to-lean-into act of care to start the day with. I often think about going to his apartment for the first time and noticing a very green splotch on the kitchen floor; he was also trying to make it through graduate school by briefly flirting with health.

The smoothies I make now are not green because I got used to making them with whatever vegetables we have at home and, thanks to our local farmshare, that usually means many, many rainbow carrots. I still think frozen bananas are the only base that produces truly creamy smoothie texture and that frozen blueberries are the only berry that offsets their sweetness without becoming too cloying or too acidic. I add rolled oats because I care about fiber more than I used to, and because they help the smoothie thicken as it sits. For protein and fat I rely on chia seeds, hemp hearts and a generous serving of peanut butter, though I will sometimes indulge in pea protein powder instead. I tend to favor almond milk, but light coconut milk, coconut water, oatmilk or even just cold filtered water all do the trick.

I like to keep most of the ingredients in the freezer - chopped bananas, berries, seeds, and the oats - so that the temperature and texture of the finished smoothie is even. I’ve never had a more expensive or more high-performance blender than the kind that you would give to someone for their first apartment after college, and I still use one from that era of my cooking. It is loud, but I only really have to tolerate that for a minute or two, a trade-off that does not actually bother me. I like to sit down and eat my smoothie with a spoon, but adjusting the amount of milk can transform it into something that you can sip on the go when necessary. It doesn’t keep for more than a day (in a closed container, like a jar, in the fridge), and because of the oats and the seeds, it takes on a pudding-like consistency as it sits, almost like if you blended up overnight oats, chia pudding and some extras.

Here are some very rough guidelines for how to make approximately two servings, but I am rarely careful with measurements and find the routine satisfying even when the final product is not exactly identical to what I ate the previous morning. In other words: please tweak it to work for you.

1 chopped then frozen banana5

2 medium to large carrots, peeled and chopped6

1/2 cup of frozen blueberries

1/3 to 1/2 cup old fashioned or rolled oats

2 tablespoons of chia seeds

2 tablespoons of hemp hearts7

1-2 tablespoons natural peanut butter

Enough almond milk to cover everything else in the blender, adding more as necessary

Combine everything in a blender, starting with the bananas and carrots and ending with the milk, then blend until it reaches the desired consistency or you cannot see whole chia seeds anymore.

Or, much more often, my editors can. This is the kind of editing that is the most painful, but also the most valuable.

Here is an example from the New Yorker, describing the mathematician Peter Shor: “Shor wears oval glasses, his belly is rotund, his hair is woolly and white, and his beard is unkempt. On the day I met him, he was drawing hexagons on the chalkboard, and one of his shoes was untied.”

Just imagine it: “Padavic-Callaghan is tall, wears lots of inky eyeliner and speaks in a low voice with a faint Slavic accent. They wear slacks and a button down shirt offset by a casual skateboarding sneaker, an androgynous and slightly rebellious take on a sensible shoe.”

I have only tried to sell and eventually sold one book, but the experience was illuminating.

Whenever I buy bananas, I chop them up and put them in the freezer right away so that I always have some at hand.

You can use a few handfuls of kale or spinach instead, but I would again recommend washing and chopping your greens then storing them in the freezer so that you can add them to the blender at as cold a temperature as everything else. I find that this also suppresses some of the more vegetal flavor, if that’s something that may bother you.

When I buy protein powder, I tend to replace the hemp hearts and one tablespoon of chia seeds with about one and a half serving of it.

Made your breakfast smoothie, and omfg it is SO good, can see why it has been your thing for 10 years

Now I’m going to read that story you reposted on the origin of the lab mouse

there is so much in your review and observations on science writing more generally that had me smiling or nodding, or got me pondering, but for starters there was this:

‘as a science writer I am used to letting go of beautiful sentences when I can identify that they serve my thinking, or my aesthetic preferences, more than they serve the reader’ — omg this has always been for me so hard, letting go of all my beautiful sentences! To be fair, I have not done much science writing for audiences beyond the academy since my younger years (and it would have then been the human sciences, where your writing starts with certain advantages over the natural sciences that are at the same time real challenges - essentially, every human on the face of the earth, past or present, is a lay sociologist/anthropologist!), and that writing was for a book rather than a research journal (and you note the expressive liberties that a book affords). But even when writing research papers I am prone to spending huge amounts of time on writing and perfecting (?) sentences that are, well, beautiful. I like to believe that my desire here is to make even my professional writing truly alive, something that will absolutely grab or even inspire the reader. But I fear it is often enough simply my aesthetic preferences, which are so hard to resist expressing. So thank you for reminding me of this painful fact, this hard reality!

And then there is this somewhat related observation on science drifting, particularly in magazines, which you perfectly capture: ‘One repeating motif that stuck out to me in this way was how often Jabr’s introductions of scientists included describing their physical features, there clothes, and often a science-related anecdote from their childhood’. You go on to note that these details are intended by writers to ‘humanise the scientist and give the reader something to hold on to while a more abstract or technical idea heads their way’ but yet find they are rarely employed successfully. I think you could also make the same point about descriptions of places, details of their sounds, smells, colors, and more.

But I have to say that I absolutely love it when these things — people and places — are brought to life insofar as you can imagine being right there with that person in that place. That is, when they are used successfully. I am pondering this because I have been re-reading Summer Brennan’s The Oyster War (having been inspired to do so by several recent things she has writing on this platform), and her method of starting a chapter with a person (often enough not scientists but characters somehow involved in the war), using not just the techniques you note but there, as well throughout the chapters, providing detailed descriptions of places on the coast north of San Francisco, the locations where the oyster war was fought, where these characters in the story live and work. But your review has made me quite curious, if you have read Brennan’s book, about what you think of her story telling techniques, or of other writers who in your view have used such techniques successfully.

Finally, thanks so much for the recipe and methods in your morning smoothie. When you said you enjoyed this pretty much every morning for 10 years now, I was very keen to learn what it was that won your heart so totally. Now I will get a chance to try it out!