All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on X, Instagram and Bluesky. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

MEDIA/DIET MARCH 2025

Thanks for reading my newsletter! This is a monthly edition of Ultracold where I share informal thoughts on media and food that I have consumed recently. A slightly more polished piece, on outfit repeating as a means of obtaining and reaffirming self-knowledge, will run on the 24th.

MEDIA

In Wojchiech Zurek’s interpretation of quantum mechanics, an observer can extract information from a quantum object through the act of measurement because that object imprints itself on its environment. Writing in Aeon, Phillip Ball offers an analogy:

If we were able, with some amazing instrument, to record the trajectories of all the air molecules bounding off the speck of dust, we could figure out where the speck is without looking at it directly; we could just monitor the imprint it leaves on its environment. And this is, in effect, all we are doing whenever we determine the position, or any other property, of anything: we’re detecting not the object itself, but the effect it creates.

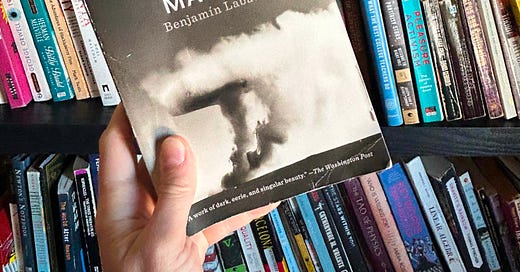

In Benjamín Labatut’s The MANIAC, at first glance, the role of the speck of dust is played by the celebrated mathematician John Von Neumann.

The bulk of the book, which is a novel rooted in thorough historical research and splits the difference between subjective fiction and supposedly objective history, centers Von Neumann. Yet, he is always spoken of in the past tense and never gets to speak himself. A chorus of historical figures from his time, such as mathematicians and physicists he worked with, and his family and friends, recount anecdotes and important moments from Von Neumann’s life. Their anecdotes are arranged chronologically so the first impression of Von Neumann is given by his childhood friend and physicist Eugene Wigner who sets up the man’s early years as a spoiled, upper class math prodigy in Hungary. Wigner also narrates the aftermath of Von Neumann’s death from cancer in a military hospital in the United States, closing the section of the book about the mathematician.

Labatut excels at giving each speaker their own distinct voice and this underscores just how towering off a figure Von Neumann was for them. He strongly imprinted himself in their lives and psyches, while also making an incredible impact on the whole world with his work on the atomic bomb, early computing and the kind of game theory that led to the concept of mutually assured destruction and shaped much of American military policy during the Cold War. The image of the man, as well as of his temperament and beliefs, emerges through the chapters which are easy to read because of Labatut’s skill, but discomforting because of the nature of Von Neumann’s work and the coupling of his intellectual might with his lack of faith in humanity and at times cruel demeanor. He comes off as a techno-optimist but dismissive, depressive and doom-inclined in most other aspects of his life.

In interviews, Labatut has spoken about “treating mathematics as if it was our lost realm of gods, goddesses, and spirits,” and writing about mathematicians as if they were mystics themselves, maybe even ghosts that haunt modern technology. He is never more successful at this than when he writes about Von Neumann, especially as he imbues him with a desire for godliness. In several instances, other characters recall the mathematician wanting to create digital or mechanical life, truly aiming to become if not a God than at least a Grand Engineer of the next iteration of physical reality.

Jancsi thought that if our species was to survive the twentieth century, we needed to fill the void left by the departure of the gods, and the one and only candidate that could achieve this strange, esoteric transformation was technology,

Labatut writes through Wigner’s voice, referring to Von Neumann by his Hungarian nickname.

But The MANIAC features several other historical characters, each of whom offer a variation on this line of needing and reasoning. They are the physicist Paul Ehrenfest, Go player Lee Sedol and AI researcher Demis Hasabis. The first is haunted by a seeming decline of physical intuition in favor of cruel and cold mathematics that humans cannot experience, the second a lover of a game which he perceives as art until an AI shows him that mathematics can transform it into something seemingly less human, and the third a creator of that very AI, someone driven by the desire to create intelligence not from scratch but from mathematics. For all three of these men, the desire to break the world down into logical building blocks that will fit together like some sort of physical reality Lego is what is really haunting them, and the shape of that spectre, of rationality’s edge, is what can be inferred from their actions and interactions, at least as they are told and imagined by Labatut.

Because of this, some reviews have noted that The MANIAC is concerned with the “unruly limits of materialism,” but Labatut does not universally critique materialist ideas. For one, he seems to be perfectly fine with the notion that intelligence or consciousness are physics problems, that building a machine, or a brain, correctly is all that it takes to reach either. He speaks of Von Neumann’s brain repeatedly, as if that biological and physical ingredient of the man can explain him fully, which betrays a kind of physicalism and eschews ideas like intelligence being anything but perfectly mathematically solvable.

This is a somewhat odd strain of Labatut’s writing as the overall arc of his protagonists’ lives does imply if not a skepticism of technology as an extreme point of an unwavering belief in reason then at least a great fear of it. His use of the language of “angels and demons” and “haunting” in how he’s talked about the book since it was published two years ago only underscores this. In this sense, The MANIAC is even more relevant now than when it was first released.

We live in a time where AI is everywhere, whether it’s necessary or good or not, and where efficiency, optimization and other buzzwords borrowed from the minds of engineers rule our lives and politics. Von Neumann thought that not only could everything be understood but it could also be controlled. His infatuation with mathematics was, Labatut suggests, in large part borne out of fear of chaos and unpredictability as he experienced them as a Jewish resident of Europe at the onset of World War II. In this fictionalized story of the great researcher, he did not want to know for the joy of knowing, he wanted to, in an almost occult way, reach secret knowledge so that he could then instrumentalize it, and turn it into a way to perpetuate his own near-godliness.

Austrian physicists Paul Ehrenfest, who is central to a shocking and tragic murder-suicide that serves as The MANIAC’s prologue, is something of an opposite of Von Neumann’s in the book’s narrative. Labatut tells us that Ehrenfest was driven mad by the fact that “sensuous relationship with the world was being replaced by a cold rationality,” and specifically the advent of quantum theory, which is mathematically incredibly successful but goes contrary to many of our embodied intuitions and lived experiences as non-quantum beings.1

The world today is run by Von Neumann’s more than Ehrenfest’s and those in power, or those with wealth, are increasingly turning away from human connections, human joy, and interdependence, and towards a presumably frictionless world mediated by machines. While reading The MANIAC I kept thinking of an anecdote told to me by a psychologist who once worked at Meta.

Their team was developing smart glasses that would let you check your email while chatting with friends or lying in bed in the morning, and the psychologist could not explain to their team-mates that most people actually just want to hang out instead of constantly parallelizing their tasks so they could get more done. The anecdote ends with the psychologist quitting the job. In The MANIAC, the fictionalized voice of Von Neumann’s wife, Klára Dán, tells us, as she is describing her well-being being ignored in favor of her husband’s work:

I felt a pain in the pit of my stomach, a sharp prick of guilt, an uncontrollable feeling of personal responsibility, no matter how small my role was in the entire enterprise, that ate away at me just thinking about what the world would look like if my husband succeeded. Because I could never be as rational or practical as he was.

But there was no company that she could quit to get out of it.

Von Neumann’s involvement with the military, which was extensive and which he had no qualms about, also speaks to the dangers of treating science as a tool and as a means to an end rather than something that is in itself profound and beautiful. This too feels incredibly poignant to me right now when institutionalized science is under attack by a government that is cutting its resources and waging an ideological war against it, and the best response anyone has come up with seems to be to say that we need to protect science because of its role in national security and because it is a source of soft power and wealth.

Science as encoded into academic institutions and government run laboratories has always been a tool of the empire and has been shaped by it, but this current crisis opens the door for remaking both science and the public’s perception of it as nothing more than that, for stripping it of all other meanings that researchers have snuck in, all those covertly more human and humanist parts of it. The MANIAC’s engagement with technology as something haunted by its forefather’s nearly demonic thirst for control over the physical world rhymes with this fear of mine, and Von Neumann’s work on the Manhattan Project is as strong of an emblem of it as a writer may reach for.

However, when Labatut directly addresses AI, potentially the big tech boogeyman of our era, in the last section of The MANIAC, I found the book faltering. While he does write the matches between Lee Sedol and the Go-playing deep learning algorithm AlphaGo with more zest and excitement than many sports matches are written about, the implications of the whole thing read as somewhat muddled when viewed with 2025 eyes.

It was simply difficult for me to take meditations on computer programs and the new frontiers of understanding, and creating, intelligence, seriously while I live in a world where coal plants are reopening, data is being stolen, copyright agreements broken, and places already stricken with drought made more arid for the sake of producing mediocre word slop that is then stuffed into emails and LinkedIn posts. Yes, I do care what studying AI can teach us about ourselves, but I also want to live in a world where winters exist and trustworthy news can be found.

The week after I read The MANIAC a colleague of mine received a comment from a source that had clearly been generated by AI and everyone in our newsroom had a real somber moment of contemplating whether our work may become impossible even before some owner somewhere tries to replace each of us with an only slightly better slop generator than that person had used.

So, when Labatut says:

We’re extruding a part of ourselves into these AIs and mirroring our faults and our prejudices and our delirium, which I find fascinating. It’s sort of telling us that there is no thought without delirium, there is no reason without tinges of madness, and that even while we’re trying to search for these beings of pure logic and high reason, they will be infected by the same ghosts that we carry around within us,

I am appreciative of how skeptical he is about the limits of pure reason, and the sinister technorationalism of it all, but also really wish to focus on the tangible damage AI is doing right now, in a sphere not of angels and demons but here among us mortals who have to sell our labor to survive instead of putting it towards anything remotely like achieving enlightenment.

One notable moment in the AlphaGo story is when South Korea’s Go Association awards this computer program a certificate for “sincere efforts to master Go’s Taoist foundation and reach a level close to the territory of divinity.” This was a well-placed dramatic line, a pure fact in a novel that is full of embellished facts, and one so good that I can imagine it was impossible to not include it. Labatut is searching for truth by blurring the lines between facts and intuition about what underlies them, and here the subtext he is driving at has been made text by actual history.

But will we ever have a chance to fully reach something like computer-based divinity given the deeply enshittification-forward iterations of artificial “intelligence” that we are currently inundated with and that dominate our technology landscape? There might as well be something profound about AlphaGo, but it’s ChatGPT’s world right now.

In my reading, one of the entities that is imprinted in the pages of The MANIAC is a reverence and awe for technology that is tentative at the beginning, under scrutiny when Von Neumann advocates for it, and increasingly tangible, and allowed to assert itself with fewer and fewer caveats, in the book’s final few chapters. Reading interviews with Labatut clarified some of these flashes of credulity and inadvertent techno optimism that I occasionally bumped against in this otherwise stunning book.

I learned that Labatut believes that he cannot understand mathematics, that he is almost hardwired to appreciate it as something mystical rather than for finding a way to access it in its full complexity and rigor. This is where my personal bias comes in, not because I have ever been all that gifted as a mathematician or a physicist, but because I have always believed that neither field is inherently only accessible to a select few.

This may also be a good place to mention that most of Labatut’s characters are men, and that if he is using their writings and stories to access the knowledge that he feels he does not personally have the aptitude for, then that process is certainly filtered through traditionally male viewpoints, and largely straight ones2 as well.

I have found a very fertile territory in this massive mathematical landscape which is teeming with beings that I know are to my mind very much akin to what we think of when we think of angels and demons,

Labatut says in one interview, and I am certain that this is crucial for the quality of his writing. But all such beings can also be tricksters - and incredibly good at delivering on shock and awe when shock and awe is what those of us that aim to encounter them are sort of already looking for.

Does Labatut’s own experience of mathematics as inaccessible set him up to see figures like Von Neumann as otherworldly? Could he ultimately be producing stories about great and terrifying men that may serve as cautionary tales, but also uphold exactly the sense of awesome exceptionalism that those men wanted to cultivate to begin with? Just like fact and fiction are blurred in his writing so are instances of critique and inadvertent lionization. My best guess is that he would say that he is doing neither, that any such act of alchemy is fully up to his readers.

I loved how he described his process to Lampoon magazine:

It’s like I’m trying to do a little physics. I’m trying to tear something fundamental apart, and that’s how you come at the materials that you’re interested in and the things that you then do with those materials are in the service of something. I am trying to fashion some sort of ritual or spell with the information. It’s then simply telling a story. It’s not normal research. It’s sort of occultism.

and we all bring an awful lot of ourselves into any sort of spell and ritual. Reading The MANIAC clarified for me just how much goes into the brew that ultimately produces a fear of technology and knowledge, a reverence for it, or a little bit of both. I read this book like I was in a trance.

DIET

My memories of shelling dry beans on my grandparents’ terrace are not the most sharp, but I can picture cracking open leathery yellow-and-red pods and shaking out their contents into bowls pretty well. Each pod would reveal several beige beans marbled with maroon or garnet spots and curlicues. Though I was not a huge fan of eating them as a child, especially because they were almost always served to me in some stewy dish whose name ended in “i fažol” (and beans), it was undeniable that these beans were gorgeous.

“Fažol” was the catch-all word for almost every bean we ever ate so when I moved to the United States as a teenager and started encountering beans with different names, both my childhood in the vegetable garden and my ESL education revealed themselves as having been incomplete. While I ate meat, I could get by with a few descriptive words for beans, such as “black” or “kidney.” Once I went vegan and started to read recipes more broadly and with renewed vigor, however, my legume vocabulary had to expand. I started wishing I had asked my nonno more questions about his fažol.

I have filled-in some of my bean-sized knowledge gaps over the years, but I still get very excited when someone brings me a bag of them from a trip or points out a restaurant dish featuring a variety that is new to me. So when my partner, whose childhood nickname happens to be “beans,” got me a bean gift set from Rancho Gordo this past December, I squealed and teared up over the shiny dried oblongs buried under layers of shredded red paper and cardboard.

I am writing this at the very beginning of March and all that is left from that box is a bag of garbanzo beans, which I am saving for a week when I might have time to not just make falafel from scratch, but also pull together all of the sides and accoutrements that make a falafel-based meal truly great. This includes properly fluffy pita bread, crunchy pickles, briny olives, a chopped salad of cucumbers, tomatoes and parsley, and a silky lemon and tahini sauce. The pace and the sheer number of hours of my work lately have not been friendly to this project, but I did manage to find time to cook the rest of my bean gift.

They were large and creamy royal corona beans, thin-skinned and very fažol-like cranberry beans, small and midnight black beans, and domingo rojo red beans. My partner riffed on red beans and rice with that last variety, but I cooked all the rest of them - and surprised myself by cooking them all in a very similar, very minimalist way.

During my first few years of not eating meat, I often treated beans as an anonymous protein that could be swapped for any animal product without much fuss. This does work and you can make great bean stews and soups, chicken-style bean salads for sandwiches, endlessly iterate on bean chilli, add beans to salads, add them to pasta, turn them into fritters and bean-balls, turn them into dips, or drown them in some beloved sauce such as buffalo. I’ll still endorse all of these variations, but this winter what I found myself craving were beans that taste, well, just like beans.

I would cover the dry beans with an inch or two of water in a pot, bring them to a boil then lower the heat to simmer and simply let them be for 45 minutes to an hour. At this point, I would add a few quartered onions, some smashed cloves of garlic and, occasionally, some dried herb and a few dried chillies or a cubed root vegetable like celeriac, with details depending on the bean and what in my pantry looked the most alluring at the moment. I would then let the beans simmer with the lid on for another hour or so before checking to see whether they have softened.

I always followed Rancho Gordo’s suggestion and only added salt once the beans were mostly soft, but I added it generously. And I always let the beans simmer until they were not just soft enough to eat, but genuinely creamy. When I remembered to soak the beans in advance, they cooked faster, when I didn’t they just patiently simmered on the stove for an extra hour or so. I finished the corona beans with olive oil and lemon, cranberry beans with smoked paprika and a touch of maple syrup, and black beans got a squeeze of lime and a dash of chili powder.

At this point the beans were ready to be served over rice, alongside potatoes, with elbow or some other small cooked pasta mixed into their broth, or alongside a few thick slices of toasted sourdough and a big side salad. I loved being able to taste the differences in taste and texture among the different varieties. Even though I cooked large servings that I could stretch over a few days’ worth of dinner and lunches, I never really got bored. Below are a few examples of how I ate the beans.

I do wish the book explored this more and spelled out Labatut’s interpretation of Ehrenfest’s anxieties in more detail. Even as someone trained in quantum physics, and who writes about it all the time, I was struggling to parse how exactly Labatut was conceptualizing it within the story.

I write about this some in my forthcoming book, but the connections between queerness, or queer thinking, and the way physicists discuss the quantum realm are really rich and, I believe, can be useful.

I've picked The Maniac up like 5 times but never committed, this might be what gets me to actually dig into it!

I love the romance with which you write about dry beans! I feel so similarly since incorporating more dry beans --- and the ritual of soaking and boiling---in my meal prep. P's brother's xmas gift to us is always fancy dry beans, and the first year he got us Rancho Gordo. :)