All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on Instagram and Bluesky. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

MEDIA/DIET MAY 2025

Thanks for reading my newsletter! This is a monthly edition of Ultracold where I share informal thoughts on media and food that I have consumed recently. A more polished longform piece, on riding trains in New York City, will run on the 26th.

MEDIA

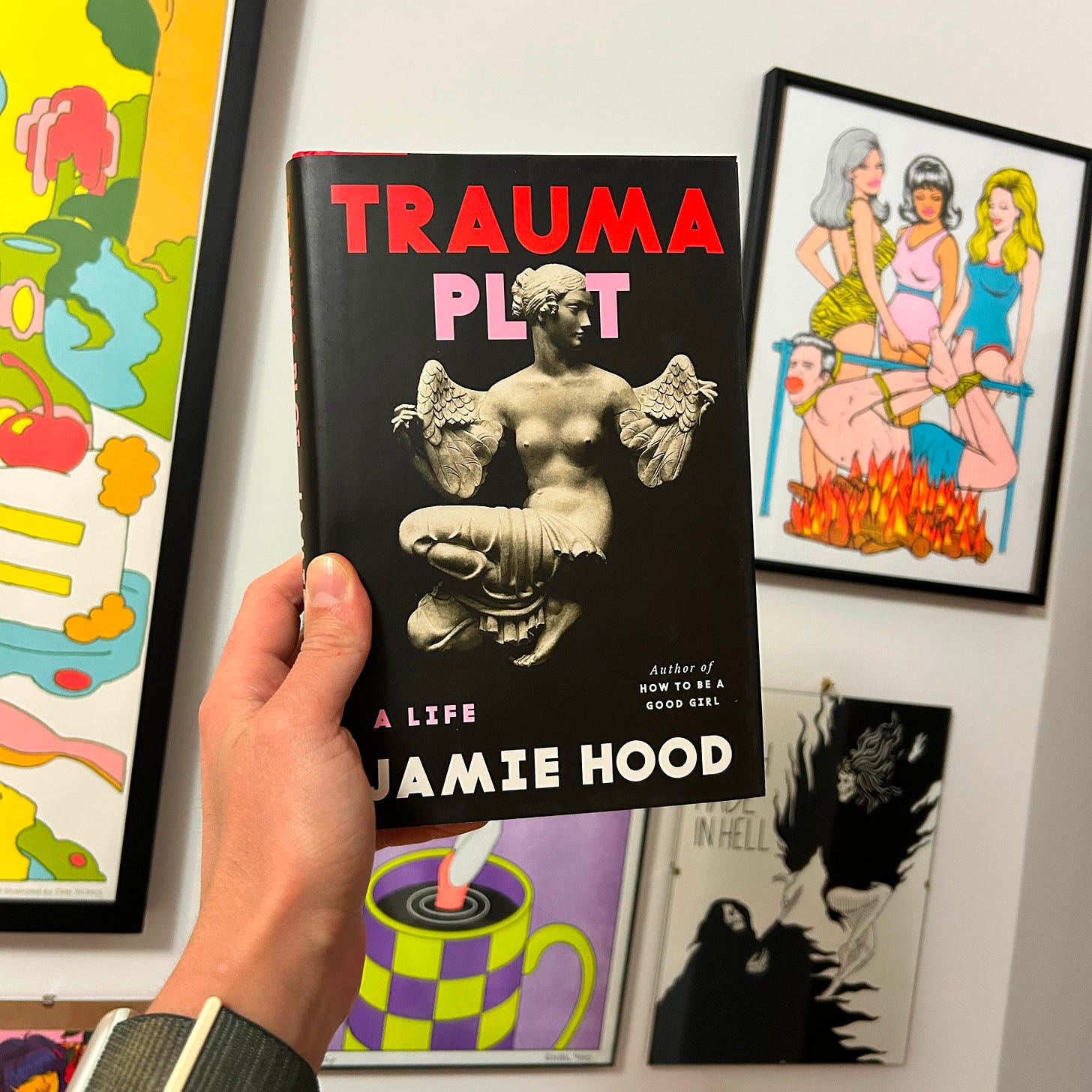

There are two important characters in

’s Trauma Plot: herself and time. They are not antagonists per se, but it is unclear whether they ever really know what to do with each other. Ask a physicist what time is, and they will hedge, waver, and try to talk math to you. Hood, on the other hand, presents a visceral account of the way time passes, penetrates, envelops and shatters. Her story is one of trauma and violence, but also a story about constructing and reconstructing a self, which is contingent on a solid grasp of time, and about the role storytelling, which also has time as its backbone, in that process.Trauma Plot is told in four sections, titled “She,” “I,” “You,” and “We,” each of which captures a different part of Hood’s life, and how sexual and gendered violence has been part of it, in a different literary style. The first section is written in third person, as if Hood was a character outside of herself, and one that she has some remove from. The second section follows a dramatic moment of rupture in which Hood addresses the reader directly, noting that she cannot avoid the “I” any longer and must tell the next portion of the story in first person.

This is followed by a section in which present-day Hood constructs something like a biography of one of her past selves, working out of diaries in an almost archeological manner and addressing that past self as a “you” in a tone that is not without love, but can certainly be clinical. Here, Hood begins to analyze not just her past actions but also her previous analysis of those actions and how the story of this past Jamie has served her throughout the years.

The final section of Trauma Plot picks up on this by presenting another set of diaries, now written in the first person and recounting Hood’s sessions with her therapist Helen. Here, Hood is more explicitly doing the work of meaning-making and grappling the violence that had been done to her, and she is assessing and unraveling her need to not just narrativize it all for herself but to write a book about it. Several entries into this section of Trauma Plot end with the therapist’s simple phrase “I am mindful of our time.”

But the notion that Hood writes time in an extraordinary way occurred to me much earlier in the book, several dozen pages in where she describes third person Jamie’s fantasy of ducking into a coffee shop in the middle of a busy and disorienting day:

“She could sit in back, reading, or perhaps people watching, quietly hollowing herself. This small window would be the only unplanned sequence of her day. She could become an urn of time, but voluntarily, and time would pass through her, opening her, summoning a universe entirely apart from her dead, bland, cramped life.”

Similarly vivid sentiments occur throughout this section, like when she writes:

“Here or there the past, like a boa, would surface, and heave its wriggling weight across your time-reddened body, clutching at your fragile throat. Choking the words out. We were only tenuously tethered to the now: time's most pitiable vessels, Jamie thought, chipped at by every minute, every second, then eventually the years would lay themselves like marble slabs on your chest.”

At this point in the book, the reader knows something bad is about to happen: Jamie keeps seeing a ghost and referencing a terrible night from her past. Hood’s introduction to Trauma Plot very directly lays out that Trauma Plot is about rape so what the bad thing is is not exactly a surprise. But the first section of the book culminates with Jamie reaching for the memory of that rape which is to say that it culminates not with something bad happening but with something bad that has already happened.

The passage of time is not pushing Jamie forward towards some terrible future, it is instead unable to carry away a terrible past that is now also a terrible present. In other words, time seems to be malfunctioning for Jamie. She is not living in the past, she is split across different moments in time. She is diffused throughout a timeline that keeps looping onto itself, her sense of self shattered because time itself has broken. In the introduction, Hood writes:

“I was undone, and I couldn’t fix it sweeping fragments into a dustpan. The shards were the book, violent and strange. I dance among them.”

Much of Trauma Plot, however, is spent with Hood in something like a sweeping posture, finding a way towards that dance. When Hood designates herself “an urn of time” and “time’s more pitiable vessel,” that struck me as an expression of both mourning but also an inability to let go. In the first three sections of the book, it is hard for Jamie/Hood to identify a desire to keep going, yet time won’t leave her alone. What is a newfound hunger for life at the book’s end, and a desire to be filled with it, is for a long while just a somber acknowledgement that time simply cannot but push her forward. When she writes about time filling her up, it almost reads as another act of violence that echoes men who use her as a vessel for their desires and enter her body without permission.

Her reality keeps getting shattered, time is breaking all around her, and yet she must keep trying to construct a sense of selfhood that can carry her into something like a future. The title of the book is a reference to an essay titled “The Case Against the Trauma Plot” by Parul Sehgal for the New Yorker, which set off an awful lot of discourse in 2021 by putting forward that the trauma plot “flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom.” But Hood is in no way flattened or reduced by her trauma. If anything her process of creating a sense of self, of stitching together all the people she has been, wants to be and might have been, all of whom were interrupted or somehow marked by violence, is made more complicated. That she has to do that complex work is part of the violence’s aftermath. As Erin Vachon wrote in the Rumpus, “The subtitle to Trauma Plot is A Life, suggesting that no narrative exists outside trauma anyway, that plot is trauma itself.”

Trauma Plot is not a light read but it is incredibly immersive, a testament to Hood’s craft as a writer, and I could not put it down1. There’s some irony in this, me barreling through the pages in neat chronological order, connecting the dots as they were presented to me on the page, while so much about what is at the core of the book underlines how difficult continuity of personhood across time is. Hood writes

“The revelation after coming to New York - thinking I'd be somebody else - was that I'd always ended up being only myself. For a time that was its own trauma, this having to be the woman I was, this having to carry the history I carried.”

But also

“The way trauma annihilates time seems to me one reason we consider it “unspeakable.” What we mean, perhaps, is that it disorders narrative, for what is a story without time?”

It is not just that Hood is a vessel for her own history, it is that putting that history into a neat chronological timeline does not empower her or help her derive more meaning. At one point, she starts writing the “Chronology of My Life and Trauma,” to share with her therapist, but ultimately never does. The exercise is more overwhelming than informative as the information that populates the chronology already exists within her, she already knows it as intimately as a person can know a part of themselves.

Trauma Plot as a whole makes for a strong argument against presenting linear and simple stories as the only acceptable form for discussions of rape. Packaging an event that turns reality into disordered fragments into a neat “before” and “after” affords frictionless comprehension, maybe even comfort, to everyone but the person who was raped. Hood’s book contains several descriptions of her rapes and there is absolutely nothing easy about reading them. But they also do not feel didactic or like they are there for any reason other than that she had to make sense of them.

She couldn’t look away from their annihilatory effect, from their warping of time and selfhood, so any reader who wants to move past unfairly reactionary impulses towards, for instance, pity or blame cannot look away either. The book feels like such a fever dream, a sort of jump-laden haze, because that is the only way for it to be honest. “One of the things that felt important to me was to not coddle the reader. It wasn’t pretty to live through this, why do I need to stand on the edges of this idea?” Hood told Paper magazine.

I wish I could take a detour here to tell you something settled, objective and perfectly value neutral about the physics of time, but I really cannot. Hard science does not offer any particularly steady handholds here. Some physicists believe that we live in a perpetual present and all else is an illusion. Some would tentatively argue that space and time both emerge from something more fundamental but also more abstract, like the flow of information at some imperceptibly small quantum level. Some are perfectly content to say that time is just a tool we use to add more order to our experiments, that as long as you have a clock and get good use out of it, it probably doesn’t matter to know what time fundamentally is or why we experience it.

Of course, even here you run into trouble - for about a 100 years we have known that any clock that moves incredibly quickly, or close to the speed of light, ticks more slowly than one that you may have in your home right now. Gravity can play similar games and the world’s best clocks, which harness quantum effects, have taught us that their ticks, what we call the passage of time, change speed when they are far from the Earth and its gravitational pull.

As every other physicist, I learned to write my equations with variables “x, y, z” and “t” and to not ask all that many questions about that last one. Reading Trauma Plot reminded me, and in such a visceral way, that writing may, in some cases, actually be as, and possibly more effective at getting to the bottom of how we interact with time as physics purports to be.

And Hood is not writing just for the sake of writing. Her experimentation with storytelling as a form is not just an intellectual exercise, it is a reflection of her truth and the truth of her body. In addition to descriptions of bodily harm, Trauma Plot is filled with descriptions of Hood walking her dog or otherwise moving, offering a counterweight to some of her more abstract grappling with what has been done to her, especially in the last section of the book. Many therapy sessions are followed by dog walks: after Hood’s therapist calls out the end of their allotted time for the session, time keeps moving and now, instead of letting herself be filled and pushed, the writer moves too.

Trauma Plot does not end on an uncomplicated note nor does it feel possible to identify some pithy line about what Hood has learned or what we the readers are supposed to have learned, but it does close with a sense of building momentum, of something kinetic. So much of the book is permeated with a sense of time as something heavy and viscous, something that makes it hard to be anything but stuck and haunted, but in the book’s final pages some of that heaviness lifts, and the writer seems to find a way to be buoyed, to look forward and see something other than more of the same muck.

In interviews, Hood calls herself an optimist though she is cautious about calling the book cathartic. In a final paragraph, she writes: “I don’t know my desire, yes, and yet I’m filled with it,” which captures some of that sentiment, an optimism but not one that has all the answers, not one that can offer a neat ordering in time, or a definitive end for having to sort, and keep sorting, life into plot. But being filled with desire is so much different than being time’s pitiable vessel.

One of the qualities that most recommends Trauma Plot is that I never found myself detached enough from its narrative to feel the need to speculate on what may happen next. I never lifted my head to think “will she be ok?” nor do I think the book was written for a reader like me to ask that question. Asking it would, in some sense, flatten Hood’s story and personhood. But there was a moment in one of the later therapy sessions where the diary entry that follows it ended with

“We’re coming to time, says Helen. And I see we are.”

And for a split second I found myself wondering whether the writer was about to make a peace offering to time itself, as satisfying of an ending as many of us can probably ask for.

DIET

All of my days start the same way: with a cup of coffee brewed just like any Croat would have brewed it. Though I sometimes claim that it was the six and a half years that it took to complete my PhD that fully turned me into a coffee fiend, the truth is that caffeine is integral to my culture, and one of its few aspects that I have stayed fully committed to.

Coffee plays an outsized role in Croats’ lives, whether it be sharing it with family after a meal at home, with colleagues at a cafe after work, or during a lunch break. Going out or to someone’s home for coffee is often a multi-hour affair, and even when the servings are small conversations run long and it all ultimately becomes an excuse to lounge and escape any semblance of a schedule. One blog even lists 25 different phrases and rituals associated with coffee in Croatia. Another recommends: “If you are a traveler on your mission to explore Croatia, having a coffee for hours might be the right thing to do. Sitting for hours, chatting, or just quietly enjoying your company and your coffee is very common for Croatians.” I even found a Forbes article on how Croatian coffee culture may shock you by how slow and leisurely it is.

It is also an example of where, to put it crudely, East and West met in Croatia’s history. The coffee we drink at home is prepared in a way that was first introduced by Ottoman invaders in the 15th and 16th century, but the coffee we order in cafes is a pretty faithful duplicate of what you may find in Italy. In my Croatian high school, the most popular coffee order was a macchiato, but the coffee that my nonna made at home was called “Turska” or Turkish. The latter is my preparation of choice now, though I have learned that in the United States ordering Turkish coffee in a restaurant usually gets you a more sweet beverage that is also often flavored with cardamom.

It makes sense that the coffee recipe has changed since it was first brought to the Balkans hundreds of years ago, and given that Croatia was long part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire or the Habsburg Monarchy, the influence of Viennese coffee culture was certainly part of what shaped it, in addition to the country’s historical ties to Italy and, specifically, to Venice. The Turkish moniker has been hard to shake in part because most Croats still own and use a special coffee pot which we call “dezva” after Turkish “cezve.” I partake in this too - I still use a really beat up red dezva that I brought from Croatia to my college apartment in Chicago sometime in 2010.

I could have certainly bought one in Chicago too and I could have replaced this one anytime since I have moved to New York City, but I like to think having a really old dezva that once loitered on Croatian soil imbues my coffee with just a little more essence of my once home. I particularly like this when I use it to make a cup for a friend, which makes me think of how so many people in my family have previously made coffee for me, a sort of mirroring of good will across continents and timelines. It’s nostalgic and saccharine, but I have lost a lot of my connection to Croatia over the years so whatever still feels good to cling to, well, I cling to it hard.

To brew coffee in the Croatian style you need water, sugar and coffee beans ground almost as fine as you would for an espresso machine, but ideally just a little more coarsely. I have ground my own beans in the past, though for best results I recommend buying a Turkish brand or, if it's available, Franck’s “jubilarna.” Vacuum sealed “bricks” of this coffee are widely regarded as the golden standard in Croatia, so much so that you’d gift them to the hostess of any family party or even bring one the first time you’re meeting someone’s family or some older, dignified relative. I also like this brand as well as this one, but I suspect that’s partly the expat in me talking. If you don’t have a dezva you can use any small pot - when I have to make more than the three cups that fit into my dezva, I often simply use a saucepan.

The recipe I am about to outline is fairly approximate because everyone’s way of making coffee, or “kava” in continental Croatia but “kafe” on the Northern coast where I am from, is fine tuned to their own taste. Some people insist on always making a whole cup more than you actually think you need so that you can pour for everyone without ever hitting the sludge that inevitably settles at the bottom of the dezva. Some people insist on waiting at least fifteen minutes before pouring any coffee out of the dezva. Even how many times you let the coffee boil can be controversial, and everyone has their own take on just how much sugar is too much.

My ideal ratio is half a teaspoon of sugar for every small cup of water and to get the number of teaspoons of coffee I double the number of cups of water then add one. This means that to get one cup of coffee I use three teaspoons, five teaspoons for two cups, seven teaspoons for three cups and so on. This is, again, idiosyncratic to my idea of what the right cup size is and how much a teaspoon should be packed. My favorite cup clocks in at about 175 milliliters or about 3/4 of a cup and I use a heaped teaspoon, but the kind you would mix tea with rather than a proper measuring spoon. Here is what I do to make two cups for me and my partner every morning.

First, I fill both of our cups with water and pour that into the dezva. Then, I put the dezva on the stove, turn on a medium flame, add one scant teaspoon of sugar and mix well, until sugar is dissolved. I wait for the water to boil and when it starts to visibly bubble take the dezva off the flame then mix in five heaped teaspoons (again, the mixing kind, not the measuring kind) of coffee and stir really well before returning it to the burner.

At this point, I am usually glued to the stove watching the coffee boil. It starts to bubble and foam at the edges then rise towards the top of the pot very quickly. When the foam has rise nearly to the top of the pot, I turn off the burner and mix again. Then, I let the coffee boil for the second time, again shutting down the burner right when it looks like the coffee may overboil, stir it one more time, then let it sit for a few minutes before pouring into the cups.

This method produces thick coffee that is neither bitter nor cloying, but it does also get you some sludge at the bottom of the cup, especially if you drink it the Croatian way - leisurely and alongside lots of conversation. The sludge does not have to be a problem: according to my nonna, once you finish your coffee you can flip the cup over and look for omens concerning your future in the way the sludge runs down its side. I’ve shared many coffees with her, even when I was fifteen and she really thought I was too young for caffeine. The only thing the sludge ever showed her in my future was that I was about to take a long trip. I guess she was really, really right.

At one point I was reading this book on the M train and got so engrossed that I didn’t realize and acquaintance was standing next to me and trying to get my attention. They wanted to get my attention to tell me that they also loved this book.

I skipped this one because I want to wait til I'm done with Trauma Plot (I started during peak semester stress and knew I had to wait/my body was too underresourced). Anyway, I'm still saving that part, but I scrolled ahead and I am feeling so warm about the Croatia coffee talk! Pretty much *exactly* two years ago I was with P's Croatian friends drinking this exact coffee and reading fortunes in the sludge, while Eurovision played in the background. <3 So grateful for this cultural sharing you offer, and feel lucky that I got to experience it.

So glad someone is writing about time-sense in her work, it's deftly done and deep! First batch of reviews didn't fully attest to how important her book is.