Vacuum Fluctuations

On turning 34

Thanks for reading my newsletter! All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. Find me on TikTok, Instagram and Bluesky. I’d also love it if you shared this letter with a friend.

Ultracold publishes every Monday, featuring weekly short essays, and monthly Media/Diet and Big Essay features.

VACUUM FLUCTUATIONS

When we first meet Lynn Peltzer in the 1984 horror comedy Gremlins she is feeling low. She’s wearing a boatneck blue dress, her hair is short and tightly curled, and she is dicing something non-descript and beige while a small black-and-white TV plays It’s A Wonderful Life nearby. Her shoulders are rounded, she looks on the edge of a heavy sigh. Her son, Billy, who is the film’s protagonist, tries to ask what’s bothering her but his first attempt is rebuffed and the second gets interrupted by the arrival of his father.

Billy’s father and Lynn’s husband is an inventor, and not a very good one at that. Lynn’s kitchen is littered with gadgets that seem useful but malfunction so spectacularly that the film keeps returning to the failure of each of them - an egg cracker, an orange juicer, a coffee maker - as a separate gag. The often repeated observation that technologies that were meant to liberate housewives and homemakers only ended up putting extra work on their plates is doubly true here. Lynn has to work with malfunctioning devices and she has to do the emotional labor of not showing despair over that in front of the husband that invented them.

Though it is implied that her original saddened posture has to do with an incident with Billy, the local Scrooge-like figure and the family dog, which opens the film, it feels completely plausible that her shoulders are always a little rounded with discomfort, in an almost defensive crouch over whatever the men in her family may bring upon her next. But when the titular monsters spawn in her home, that she quickly assumes a fighting stance.

Faced with an attack by five Gremlins, Lynn doesn’t run or wait for help. Instead, she arms herself with a knife in each hand and charges at them as they saunter into her kitchen. One decapitated Gremlin’s head ends up in the microwave, another little monster meets their fate head first in the juicer, splattering across the cabinets. The gadgets are finally working for Lynn. She doesn’t take out all the Gremlins, and Billy does barge in mid-fight as something of a savior, but for several delicious minutes, just as it has become clear that the film is a horror after all, it’s just Lynn and more aggression than you think can hide underneath a 1980s perm. When I saw Gremlins at a local theatre recently, this was my favorite part of the movie.

The idea of a ‘gremlin’ originates with Royal Air Force pilots in the 1920s, who blamed the fictional creatures for any unexplained aircraft malfunctions. In 1929 a aviation journal published a poem calling gremlins a flyer’s nemesis, and by the 1940s reports of them started appearing in American papers as well. They even got a shout-out in Charles Lindbergh’s autobiography, and appeared in a 1963 episode of the Twilight Zone where a gremlin tries to sabotage an airplane in front of the eyes of a terrified passenger played by William Shatner.

This lore is also referenced in the film, through a character who is a veteran. Most of what he does in Gremlins is bemoan the failures of technology that’s not made in America and drink too much, which makes for a rather unkind portrayal of post-war trauma. Like most characters in the film, he is a caricature but still tethers Gremlins to their origin in a place of fear and failure, which is otherwise erased when the movie recasts them as spawns of a very cute creature called Mogwai. Airmen needed Gremlins as something to take the blame for their failures, or maybe a mechanism for making their bad luck seem a little less unpredictable, faceless and random. I was struck by the notion that all new technology, and especially technology that can kill, is terrifying, so much so that you might as well imagine it running over with tiny monstrous creatures instead of confronting your own role in supporting and operating it.

Lynn is then the perfect foil to the gremlins as she is already sick of fighting with the gadgets and other, less literal, mechanisms of domestic life. She may already craving a way to purge her juicer and egg cracker of their hiccups and glitches - or maybe just destroy them altogether. I think that’s why her determination to fight the gremlins resonated with me so much. This past year, all the technologies that kept my life going, be it the system that’s supposed to turn my labor into a living, or the stories I tell myself about what reality is - and story may be the oldest technology of all - felt so glitchy.

With amazing regularity, there was always something that had just broken or was about to break, some glitch that threw off my routine, put some small hope on pause, or gave my body a reason to falter. I did so much this past year, I was so terribly productive, yet a feeling of dissatisfaction hovers over many of my 2025 memories. I wish I could blame some gremlin for all of that. Instead of confronting the reality of the situation and my part in it, at the end of my 33rd year1, I wish I had something I could grab and throw into a juicer. I’d even welcome the greenish, gooey mess.

My year started with a feeling of anticipation, of some impending transformation that I could not fully articulate but that twinkled within me, seemingly promising a fire. Maybe this was about my writing career and my first book, maybe it was about my body and feeling steady in my gender, maybe it was just the spell of being in my Jesus year. But the year quickly shifted into what now feels like months’ worth of haze, that glitchiness that made everything feel not quite right and filled me with the emotional equivalent of static on old TVs.

I’m not sure what triggered it. Maybe it was the state of the world, maybe it was something in my own microcosm, maybe it was just that thing within me that has always loved to wallow and cosplay martyrdom. I worked a lot, I ran a lot of miles and punched a lot of boxing bags, I went out to dinners and movies with someone, or someones, I love as often as I could. The low feeling kept simmered underneath most of it. I thought this may be the year when I become somebody, but now, writing this in the anticipation of my birthday, I am struggling to remember whether I felt like anybody at all for most of it.

A week into December, my best friend offered me a reality check - they remembered a springtime bout of depression, an awful lot of fear over my long uncertain immigration status2, and the never-ending aftermath of now old heartbreak. “You did finish your book,” a chorus of loved ones additionally echoed on several occasions. In early December, setting up to sell slices of vegan cakes that I had baked the night before, my best friend and I went through the list of goals and intentions for 2025 that we wrote together last winter.

Some were very silly and attainable, such as eating more frozen berries and cooking with leeks, and some were serious, such as joining a credit union, which we both failed to do. We both excelled at going to the farmer’s market and taking the bus, to the point where it felt almost like a cheat to have ever put it on the list. Neither of us did well with “putting phones in a different room,” and we immediately agreed to put it on the list for 2026 too. Was this year a wash, I meant to ask my friend as more unaccomplished goals came into view, but our list had been long and people were starting to come by for cake. Our year-end-audit had to be abandoned before we managed to finish it. But the question lingered with me: what do you do with a year that feels like a wash?

I spent the second week of December in California, rubbing shoulders with leaders of the burgeoning quantum computing industry. It wasn’t my first time in this convention centre in this particular tech park in the Silicon Valley, but every hour away from New York’s walkability and mostly functional public transit still unsettled. The mood, however, was good. There was a healthy amount of enthusiasm permeating the dry indoor air, and several speakers and panelists seemed almost surprised by their own optimism. In a year where many areas of science, and many scientists, have felt and been under assault, this made me feel like I had unexpectedly entered a bubble.

Quantum computers are a radically new type of computer, running on mathematics distinct from those that underlie any computer that you have ever used. Their tiny components harness quantum effects, the kind that are completely inaccessible to large creatures like us, to gain more functionality than more conventional machines. It has been rigorously proven that there are some calculations that a quantum computer could complete but no traditional computer ever could, even if given as much time as the age of the universe. But quantum computers have also proven incredibly hard to build, and even harder to build well. They look nothing like computers, much more like something out of a steampunk novel or straight out of a physics lab, and they often require niche specialists to operate them. Trying to build an industry around such a device then makes for a tenuous marriage of business and physics.

Because of this, encountering optimism within this industry is an interesting exercise in balancing excitement and skepticism. In my capacity as a physics journalist, I am barraged with press releases that promise quantum computing breakthroughs but reveal themselves to be much smaller bits of progress, typically over-hyped, upon further scrutiny. Of course, anyone who promises to sell you a very expensive and exotic device within a few years must be enthusiastic about the progress they’ve made so far. Why would you buy from them otherwise? As a scientist, there is also no harm in being excited by incremental progress. This is often the attitude necessary for reaching an eventual discovery. But what size of an increment is sufficient to justify pouring billions of dollars into a fast growing ecosystem of startups? And what happens when an experiments’ inflated value reaches power users on X or national politicians? Outside of academia, in the domain where money speaks as loudly as peer review, aggressive optimism becomes troublesome and can be easily abused.

So, I went to California ready to ask follow up questions upon follow up questions and roll my eyes at corporate stock phrases about how quantum technology is mere days away from changing the world. That was not necessarily absent in the three days I spent there, but I also returned to my newsroom just a bit more elated than I expected. Almost certainly, no company will have built a fully functional and practical quantum computer by the end of 2026 nor do I expect any quantum computer to significantly influence society in this decade. My priors on that have not changed. But the past year really has seen a lot of necessary ingredients for such a device to even exist fall into place. The industry has a big engineering push ahead of it, and I imagine some of the firms will not make it to its end, but the dial has moved at least a little bit away from ‘impossible scientific mystery’ and towards ‘very hard building problem.’ In my reporter’s notebook I jotted down notes on this shift, the details of enthusiasm exuded mostly by men in gray suits, with their t-shirts untucked and button downs tie-less.

When my editor asked, I tentatively admitted that I sort of do believe that it had been a successful year for the industry. Treating how much of a foundation you laid down for holding up big future promises seemed like an acceptable metric for declaring so. All the progress that happened this year, people kept telling me in California, will enable something truly stunning in the next few. Even representatives of companies that could not claim some buzzy breakthrough in 2025 seemed to be in high spirits, talking about their roadmaps and inching towards some big future reveal.

I tried to contrast my end-of-year anxiety to this rosy confluence of capitalism and science. Could I reclaim my year as successful if I identified enough small victories? Could I convince myself that I have laid the groundwork for a 34 full of breakthroughs? Of success? Had the stuff that I got done in-between, or despite, the existential glitches, been enough?

As I am not a machine after all, I realized that all the metrics I could name for being somebody or for being successful were, inevitably, flawed.

In Gremlins, right before everything goes sideways and the Peltzers’ idyllic snowy town descends into little green monster chaos, Lynn’s husband suggests that being able to force the Mogwai to spawn new creatures could be his ticket to success. Every kid in America will want one of these, he conjectures, imagining riches he could get out of the creature instead of from selling his flawed inventions.

To spawn new creatures, the Mogwai has to get wet. When this happens, his round, fuzzy body convulses and shakes before violently ejecting little furballs that then unravel into new creatures, which become gremlins if they eat after midnight. The moment it is suggested that making the Mogwai spawn over and over again could be a successful business practice, you know something bad is about to happen. This isn’t because Gremlins is a deep film, or a good one for that matter, but just because any story about a misguided desire for success, and taking shortcuts to get there, is an extremely legible one - and always ends badly.

You have to be careful about what exactly you want and how exactly you plan to get there. Otherwise, in contrast to their origin story, the gremlins end up being your own fault after all.

***

A fact from physics: If you put several hundred similar objects in a box, maybe a marble to represent every day of the year, and shook it really hard, the probability that they will spontaneously assume some truly exceptional configuration would be very, very small.

***

In the very introduction of How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, Jenny Odell questions the capitalist notions of success and productivity:

“Productivity that produces what? Successful in what way, and for whom? The happiest, most fulfilled moments of my life have been when I was completely aware of being alive, with all the hope, pain, and sorrow that that entails for any mortal being. In those moments, the idea of success as a teleological goal would have made no sense; the moments were ends in themselves, not steps on a ladder.”

Broadly, through discussing the titular doing nothing, Odell’s book makes a case for collectivism and community instead of rugged individualism and competition, as well as for relinquishing any sense of an overly rigid or fixed personhood that can turn a person into a reliable consumer and cause them to stagnate emotionally and philosophically. For instance, taking a break from social media is an individualist, short-term solution when the more fruitful and necessary outlook would be to rethink and rebuild the way we make and maintain social connections, and to do that together. How to Do Nothing is then really about doing things differently, not about not doing them at all. In fact, there is realistically almost certainly no such thing as doing nothing and Odell is interested in how systems within which we exist, or which we build, imbue a seeming nothing with somethingness.

In the same way that she discusses the downfalls of digital detoxes or social media breaks, she is skeptical of any reframing of rest, pauses, and periods that one could describe as fallow. In Odell’s view any attitude or argument that positions quiet or unproductive times as either somehow productive or as targeted incubation periods for productivity to come only reinforces the primacy and necessity of always having something to show, sell or leverage. If you only rest so that you can then extract something out of yourself, or offer for extraction to a person with more power, then that rest was secretly work too.

This is not to say that rest does not have a purpose, just that that purpose is about something internal and human, rather than economic. “To do nothing is to hold yourself still so that you can perceive what is actually there,” writes Odell. A period of stasis is then less like some sort of cocoon that will ultimately break to let out a super optimised, super functional, super regulated person. Instead, it is an invitation to take stock of what is actually real, what actually matters, and what is simply background noise once you stop thinking it important. From this place, Odell argues, we can regain and retrain our sense of attention. And she notes that “if it’s attention (deciding what to pay attention to) that makes our reality, regaining control of it can also mean the discovery of new worlds and new ways of moving through them.”

I read Odell’s book several years ago and found it meaningful, but felt the need to return to it while I was taking stock of this hazy, glitch year because I had hoped to find a bit of theory that could complement my loved ones’ assertion that I did, actually, do just fine with being 33. It offered me something more valuable - a challenge. It nudged me to ask myself what it means to decide to pay attention to my low moments and what it means if I chose to center my small victories instead.

Of course, “what is actually there,” is both. “What is actually there,” is also the tension between the two. Should I seek to alleviate that tension or should I relish it? This choice felt like the beginning of the path from attention into action into transformation. Feeling some of the haze dispelled by the realization that transformation is not only always within reach but to an extent unavoidable, I resolved to not reframe the past year as anything but what it really felt like.

You may have heard this one before because it is a fun fact that physicists tend to love, but empty space is not actually empty.

The laws of quantum physics forbid perfect certainty so a place that would be perfectly empty cannot exist because anything you’d measure about it would be perfectly, certainly zero. Instead, empty space is, at the most microscopic level, filled with acts of creation and annihilation, with pairs of particles and antiparticles emerging, crashing into each other, disappearing, then emerging again, and so on forever. Sometimes, this is unglamorously called “vacuum fluctuations.”

In 2023, I interviewed a researcher whose team found a way to use lasers to interfere with this process and even proposed building a computer-like device based on this takeover of nothingness. In 2024, another team of researchers told me about a protocol for harvesting the energy of this not-empty empty space. In the minds of physicists, the idea that there is no such thing as empty, as nothing, is then not just theoretical but a tangible reality. Even when there seems to be nothing happening, when there is no dramatic thing beginning for attention, they know to look underneath and find possibility and richness.

***

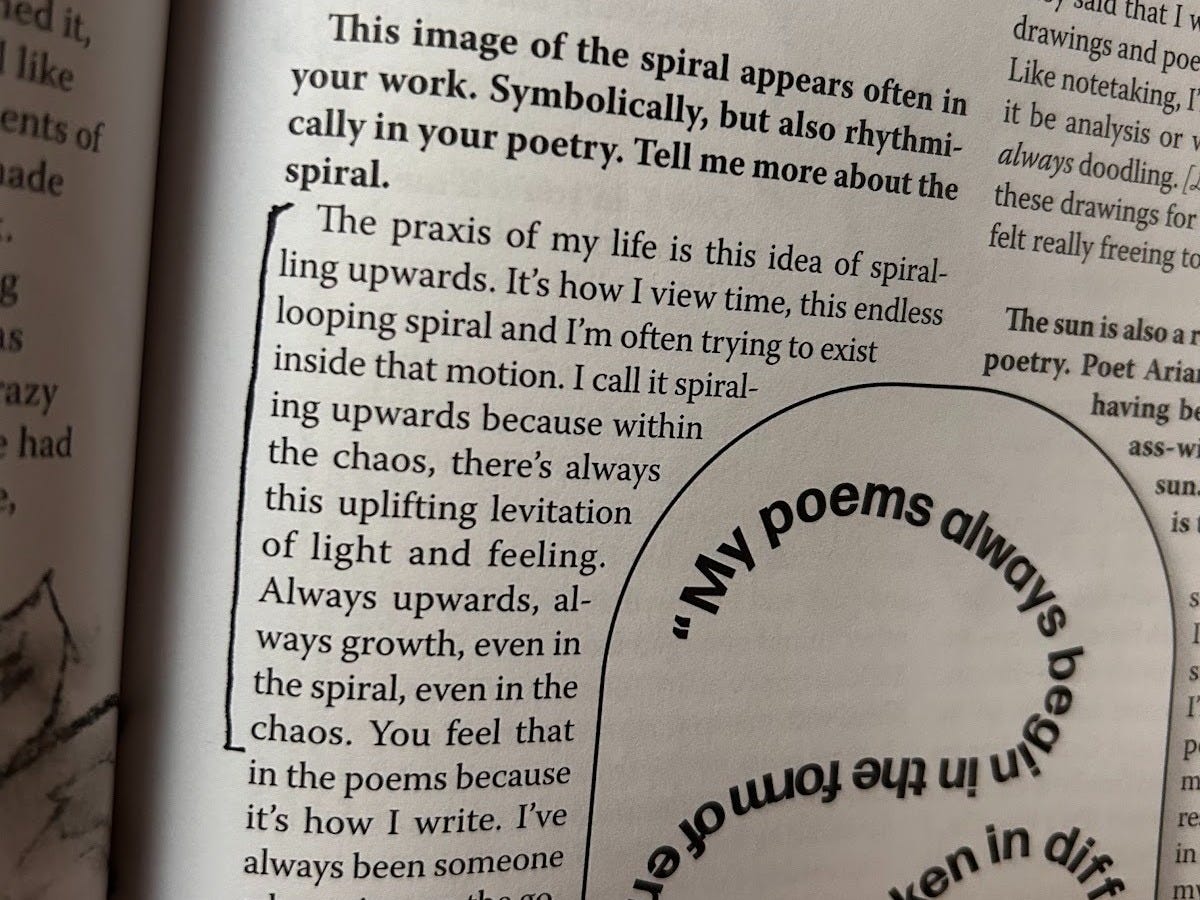

“The praxis of my life is this idea of spiraling upwards. It’s how I view time, this endless looping spiral and I’m often trying to exist inside that motion. I call it spiraling upwards because within the chaos, there’s always this uplifting levitation of light and feeling. Always upwards, always growth, even in the spiral, even in the chaos,”

poet and artist Precious Okoyomon told Worms magazine earlier this year. The idea stuck with me, probably because I am someone who tends to call things chaotic as a soft insult.

If I say my work or my schedule have turned to chaos, I am usually trying to say that I have too much to do and according to unclear guidelines. If I call a person chaotic, I am often trying to call them unreliable, or at least a little negligent to the existence of the world around them. I know the scientific definition of a chaotic system, the one where tiny happenings can have outsized effects, but my colloquial use of “chaos” is a lot more flat, just a fancier way to say that unpredictability sometimes really makes me feel unsafe and irritated. The verb “spiral” too is usually used negatively, as a metaphor for descending into a low or delusional place, as a shape that facilitates a fall towards some bottom.

This past year, I wasn’t spiraling, nor was I falling. I was suspended in some state of anticipation, then waded through a thick existential mud of amorphous dissatisfaction. Both felt like being stuck. I couldn’t find a way to free myself and float above it. Instead of a spiral, I can now, in retrospect, see a circle. It was a retreading of the same steps, going through the motions over and over again on one flat plane. Genocide abroad, rise of oppressive policies at home, layoffs at work, long aftermath of bad personal decisions, incessant waiting for my green card, it all kept my motion confined to two dimensions only.

But Okoyomon’s idea is not just about moving upwards, it is also about letting yourself become destabilized and about embracing some of the unpredictability of chaos. It is about motion and it is about growth, two things that cannot happen if all you treasure is stability. And what is more stable than being vaguely unhappy? Not in an active crisis that eventually does pass, or requires a radical intervention to be resolved, but a reliably dissatisfied and low mood, a bleak anti-chaos that has always been there for me.

Odell writes about something similar. She posits that for many young people the ability to pay attention, and choose to pay attention and what to pay it to, is obstructed by fear of instability. In a capitalist world, stability is framed as a scarce resource and something that can be lost in many more ways than it can be gained. This leads, Odell notes, to an “atomized and competitive atmosphere” that “obstructs individual attention because everything else disappears in a fearful and myopic battle for stability.”

Chasing stability through playing the game of capitalism makes it hard to pay attention and not paying attention makes it hard to imagine any other way to live. And when imagining a different life becomes hard, so does actually doing it. You get stuck in a system designed to grind you down, a little more broken down by each “glitch” that may actually be a feature rather than a bug.

So, the final part of reckoning with my year as what it really felt like is holding myself accountable for how likely I am to choose to go to the low place rather than letting in just a little more chaos into my world. I wanted to see myself become somebody by the end of the year, but even if I take that at face value, uncritically, I have to acknowledge that change has to be active, has to be courageous, and open doors to some instability. Maybe this means placing fewer bets on my job. Maybe it means doubling down on how great I think my upcoming book is.3 Maybe it means seeking out gender affirming care. It certainly means fearing uncertainty and newness a lot less.

In that same interview, Okoyomon says

“My practice is a continuous praxis of love, care and release of control… The work always starts from a place of seeking change, decomposition, renewal and grace. That’s love for me.”

As a textbook Capricorn, I might always stay a little resistant to chaos, if not outright afraid of it, but these things - change, decomposition, renewal and grace - are what I want to take with me into my 34th year, alongside paying attention to the somethingness underneath my nothing and the forces that drive me to see or not see that.

On my way to California, when I took my phone out of airplane mode at my late-night layover, three messages waited for me. One explicitly said “I love you. The other two were about sports and bread, respectively, but I also read them as love notes. They offered me something soft to lean into while dealing with flying nerves.

In my teens and twenties, I flew constantly, first to visit family abroad, then to visit a partner in another state, so I felt at home in airports and on planes. Now, I mostly fly when I travel for work, and I get stressed and tender. This recent trip to California was no different.

In the back of a car on my way to New York’s John F. Kennedy (JFK) airport I heard myself promising to keep something off the record while on the phone with a source and felt like I was in a movie. In a meeting with my manager at work the day before, I explained that I’d be coming back from Silicon Valley on a red-eye flight then taking a meeting with my publicist, another surreal combination of words for someone who claims to be a nobody. Regardless, as I waited to board my flight at JFK, my face ached in that dull way that only happens when I am trying to hold back tears.

My best friend Alex recently wrote about how traveling feels different when you actually love your home and do not need ways to constantly escape it.

“I had made a home for myself; I had found shelter within people and the life I had built around me. What was my relationship to travel at this point?”

they wrote in November, presciently explaining part of my dread over a routine trip to a three day conference.

Inadvertently they gifted me another reality check. How bad and unsuccessful could the year have been if it was so hard for me to step away from the people who love me, even briefly?

Notably, love is also part of Okoyomon’s ethos, the one that I liked so much. “Love is the miracle of being made and unmade,” they offer. In other words, there is transformation to be found here too, exactly the kind that comes coupled with chaos, community, and courage. Regardless of what else 34 might bring, I know that I can resolve to spend another year trying to be somebody who loves and who can be loved.

But maybe you knew that I’d eventually end up here. Where else could any story about chaos, glitches, challenges and changes even go? After all, even Gremlins manages to, amidst all the monsters running around and throwing life into disarray, thrust Billy into a love story with a happy ending.

***

Wishing you lots of love, meaningful nothings, transformative attention, and upwards spirals in 2026,

Karmela

I turned 34 on December 28th, but wrote this letter in advance

After several year of waiting, my green card renewal was approved this fall

Please pre-order it